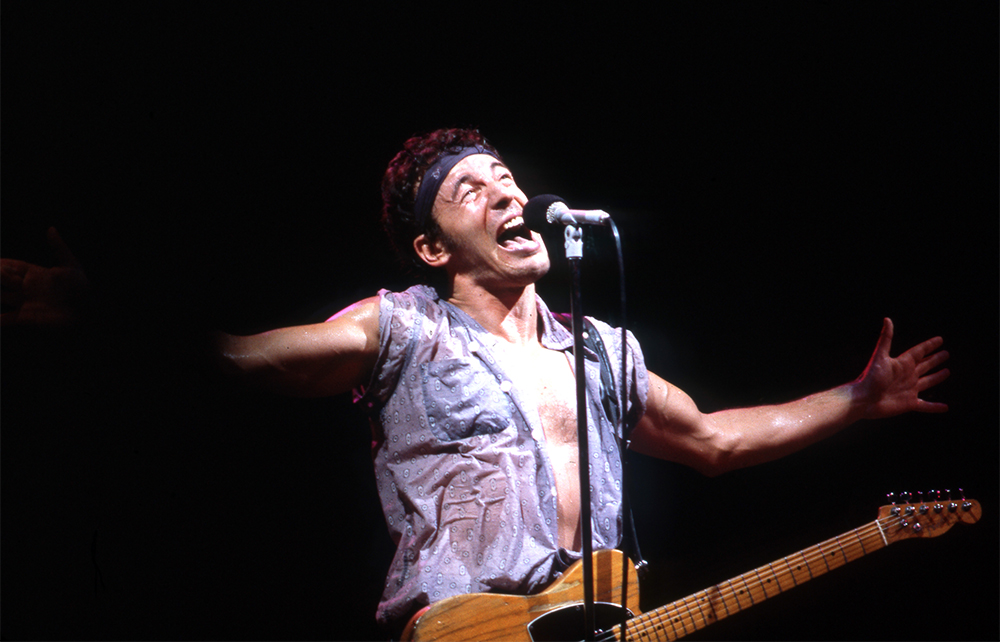

In 1977, in the wake of the death of the king of rock’n’roll, the American journalist and music critic Lester Bangs said: ‘We will never again agree on anything like we agreed on Elvis.’ The ‘we’ was America. And Bangs was right – until June 1984, when Bruce Springsteen released Born in the U.S.A.

The album’s blend of synths, guitars and colossal drums would vault Springsteen into stadiums. It went on to sell 17 million copies, and for a time made its creator the biggest rock star in the world. Steven Hyden looks to trace who Springsteen was before this moment, what happened to him during it, who he became after it – and, with more difficulty, what became of his audience. Part ‘making of’, part cultural criticism, and part socio-political treatise with occasional lapses into fan fiction, this is something of a mongrel of a book – and, in truth, if you’re not already a devoted Springsteen fan, then it probably isn’t for you.

However, there’s an interesting conceit at its core: was Springsteen the last great centrist rock star? Hyden is on the money when he pinpoints how Presley’s mythology was ‘rooted in assumptions about the exceptionalism of the United States’, and how Elvis became

the very embodiment of the heartland that exists in our nation’s political and cultural imagination… the belief that Americans are inherently reasonable and good and inclined to be generous and thoughtful if given the right opportunity.

In the Netflix documentary version, we would smash cut from these words to footage of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021.

The same editing trick would work after Hyden quotes the 1980s Springsteen saying: ‘I guess my view of America is of a real big-hearted country, real compassionate.’ Cue shots from various Trump rallies: the screaming, enraged faces of the heartland, of what was, once upon a time, Springsteen’s audience.

Back in the day, the title track of Born in the U.S.A. was, of course, claimed by both left and right – by the former for its coruscating verses and the latter for its affirmatory choruses. Hyden acknowledges that it is a tribute to the complexity of the 1980s version that it cut both ways. Three decades later, on Broadway, playing an acoustic version of the song, Springsteen would make it clear whose side he was on. But by that point, there were very few floating voters left in America – and Hyden never quite gets into how this happened.

He decided to write this book because the song ‘rewired my brain’ when he heard it in his father’s car and became an unlikely Springsteen devotee at the age of six. But his admission means that the book is sometimes wildly uneven. We get flights of fantasy about records Bruce might have made at certain points in his career (‘I’m not alone among Boss freaks in engaging with this form of fan fiction’). We get frothing sentences that would be more at home in the fanzine or the Reddit thread: ‘My God, just thinking about that solo can send a person to the couch in a foetal position for the rest of the day.’ We get questionable propositions masquerading as fact: ‘The most common criticism of Bruce Springsteen by people who don’t like Bruce Springsteen is that he is not the person he sings about in his songs.’ (Is it? I’ve never heard anyone articulate this.)

It goes on. ‘Like all Springsteen fans – or all people who have good taste – I love Nebraska.’ (Good taste being, as we know, famously easy to pin down.) There are detailed comparisons of different bootleg cuts justified with ‘at the risk of sounding like an insufferable fanboy’. Well, you can acknowledge it. And you can risk it. But you might still sound insufferable.

It’s a pity, for Hyden scores some adroit critical points along the way. He calls Springsteen ‘the rock and roll equivalent of Steven Spielberg’, the kind of artist for whom ‘there would always be light at the end of the tunnel, in which family and a larger national community are preserved against all hardships’. (Again, how does that kind of artistry look today in an America so divided that many families can no longer survive Thanksgiving dinner together?) And he is right when he pinpoints in Creedence Clearwater Revival (a band who served as a template for Springsteen’s own ‘no frills American music for the people’) what the next generation would see in Springsteen:

A kind of unpretentious, small-town liberalism personified by working-class labour unions, corner taverns that only serve cheap pitchers of domestic beer, and no-nonsense men and women who work on their cars at the weekend and reliably vote for Democrats in every election. A middle America that might still have existed in 1984, before the factories left and the opioids moved in, and now seems like a distant mirage.

At just 230 pages, this is a slight book. Had it been edited down even further and simply been called Born in the U.S.A., you could have seen it slotting right into Bloomsbury’s 331/3 series. However, once you append the words ‘and the End of the Heartland’ you’re offering the reader something else entirely, and Hyden never quite delivers on the promise of that six-word appendage, although he does come close at points. As here, in his final paragraph:

Bruce once asked in one of his greatest and most heartbreaking songs: ‘Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true? Or is it something worse?’ Now I could see that ‘something worse’ was not having a dream at all, no matter whether it was true or not. Outside the arena, the dream disappeared. All you had were the broken pieces of America.

Comments