Bradley Manning’s relationship with Wikileaks has, inevitably, brought Julian Assange back into the papers. Viewed on the frontpage, Assange is egimatic. We know what he’s done; but we know little of him. Alex Gibney’s compelling new documentary film We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks presents an extensive and revealing biography of Assange — and much more besides.

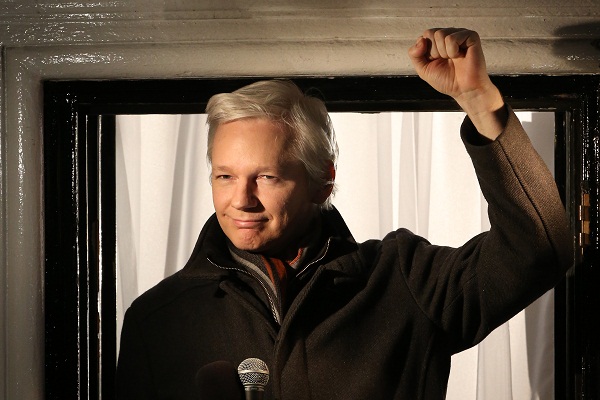

Gibney’s camera is impartial. We hear from Assange cultists, former collaborators and alleged rape victims. No two people will react in the same way to what they see. A white-haired Icarus formed before my eyes; a charismatic brought down by his own narcissism and hubris. Gibney captures one deeply ironic moment when Assange is reading fawning British newspaper coverage of his exploits and declares that he is untouchable in this country. Famous last words, Julian.

We Steal Secrets is really two films: one about Assange’s celebrity, the other about morality in a digital and political context. The latter is the more thrilling part. Most of the action follows Bradley Manning. Anyone who thinks that the Manning case is a simple matter of right and wrong ought to watch this film, for there are not enough shades of grey to depict its moral complexity.

Manning is a somewhat unsympathetic personality, at least from a distance. We hear from those who knew or served with him. And we see him authoring his own destruction:

There is honour and right in that. Yet the clip also suggests that Manning was influenced by other, less honourable motives. He appears, to some extent, to have been using his proximity to classified documents to build friendships.

Was Wikileaks right to take advantage of this vulnerable and conflicted young man? This is one of many unanswered questions posed by Gibney. Assange is a free speech fundamentalist. And, like all fundamentalists, his attitude to ‘collateral damage’ is chilling. I’m not alone in this view; plenty of Assange’s colleagues express their discomfort to the camera. One or two profess horror.

Beyond Wikileaks, Gibney shows how digital technology is affecting government. US officials cannot agree on what to do with Pandora’s Box. Would transparency make for better policy and wider public understanding of the messier business of government (and therefore negate the wrecking, so to speak, of organisations like Wikileaks)? Or do secrets need to be kept at all costs for the greater public good?

The latter view prevails. The following clip, from which Gibney took the film’s title, partly explains why Manning has, as yet, no right to a public interest defence and why he is being treated in such a draconian fashion.

My one cavil is that Gibney does not make enough of the futility that underlines the Manning case; because, despite Julian Assange’s dubious efforts, the world has not changed one iota. Did Wikileaks actually achieve much more than the brief aggrandisement of itself and the even briefer embarrassment of the United States? And, as a counterpoint to that, should Manning’s sentence be merciful?

Comments