At the heart of the crisis over the Protocol is its failure to deliver on its own stated aims. To understand this crisis, it is necessary to know some key aspects of the Protocol’s genesis and history. Exactly a month after Theresa May triggered Article 50, the European Commission was instructed by the member states (the European Council of 27) with ensuring the UK’s orderly withdrawal from the EU, including finding arrangements for the island of Ireland. That meant securing the Good Friday Agreement and avoiding a hard border. This was set out in legal guidelines on 29 April 2017 and elaborated in directives for the negotiations the following month:

In line with the European Council guidelines, the [European] Union is committed to continuing to support peace, stability and reconciliation on the island of Ireland. Nothing in the Agreement should undermine the objectives and commitments set out in the Good Friday Agreement in all its parts and its related implementing agreements; the unique circumstances and challenges on the island of Ireland will require flexible and imaginative solutions. Negotiations should in particular aim to avoid the creation of a hard border on the island of Ireland, while respecting the integrity of the Union legal order.

The Commission identified a political, not a technical, solution to the challenges posed by Brexit on the island of Ireland: the alignment of Northern Ireland with the EU single market and customs union. A simple answer to a complex problem. Unfortunately for the Commission, it had not understood the Good Friday Agreement properly, believing it to be about simply north-south arrangements.

Shortly after the dialogue began in June 2017 – and note that they were not negotiations – the UK published the only substantial document on the interlocking relationships on the island of Ireland and across the British Isles, its position paper on Northern Ireland/Ireland. It provided a good explanation of the Belfast Agreement, including its three strands: the interlocking structures of devolution, north-south cooperation and east-west cooperation. Interestingly, apart from immediately dismissing the UK’s solution for managing the customs border, there was no response from the EU for three weeks.

In early September 2017, the EU published its response: the ‘Guiding Principles on the Dialogue on Ireland/Northern Ireland’ setting out the EU’s position. Their paper reaffirmed the commitment to protect the Good Friday Agreement but ignored the careful balance of the UK’s position paper; instead, it strengthened its north-south view of the Good Friday Agreement:

It is the responsibility of the United Kingdom to ensure that its approach to the challenges of the Irish border in the context of its withdrawal from the European Union takes into account and protects the very specific and interwoven political, economic, security, societal and agricultural context and frameworks on the island of Ireland. These challenges will require a unique solution which cannot serve to preconfigure solutions in the context of the wider discussions on the future relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom.

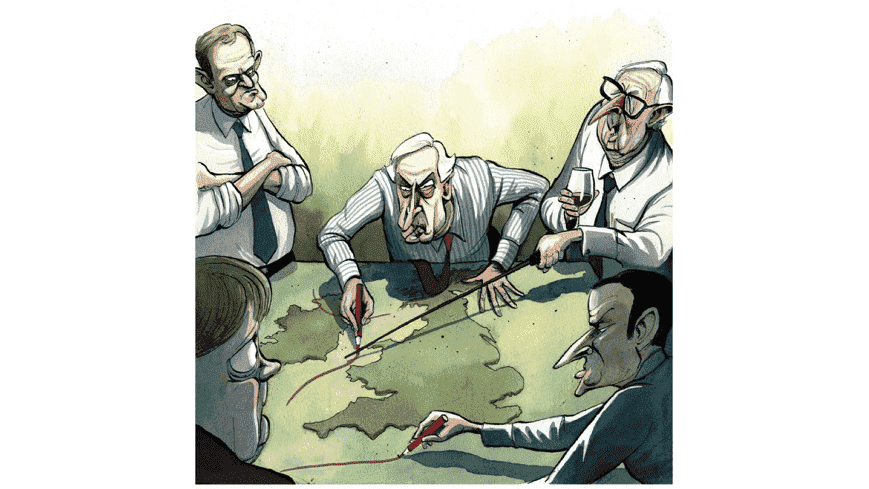

The Commission will find it difficult to own such a large-scale error

There was no mention of equivalent protection for east-west cooperation, despite the significantly higher integration of Northern Ireland within the UK, thus losing the balance of the Good Friday Agreement. It did reaffirm the Council’s instruction to the Commission that: ‘as an essential element of the withdrawal process, there needs to be a political commitment to protecting the Good Friday Agreement in all its parts, to protecting the gains of the peace process, and to the practical application of this on the island of Ireland.’ Its first guiding principle was:

The Good Friday Agreement established interlocking political institutions which reflect the totality of the relationships on the islands of Great Britain and Ireland. The institutions, which provide frameworks for cooperation between both parts of the island and between Ireland and Great Britain, will need to continue to operate effectively.

Two months later, with the UK government under even more political pressure, the EU issued a negotiating document that reaffirmed the centrality of north-south cooperation, quoting the Guiding Principles document quoted above; it concluded:

The EU and the UK have committed to protecting and supporting the continuation and development of this cooperation and of the functioning of the institutions established by the Good Friday Agreement in the context of the Withdrawal Agreement. Achieving this must be done in a way that respects the integrity of the internal market and the Customs Union of which Ireland will remain a full member.It consequently seems essential for the UK to commit to ensuring that a hard border on the island of Ireland is avoided, including by ensuring no emergence of regulatory divergence from those rules of the internal market and the Customs Union which are (or may be in the future) necessary for meaningful north-south cooperation, the all-island economy and the protection of the Good Friday Agreement.

Far from the UK being required to provide a solution, as the EU had insisted all along, it was an EU solution that was being put forward, a solution that was designed to fully protect north-south cooperation and ensure that this should be achieved at no cost to the Republic of Ireland. Not only had it prioritised north-south cooperation, and exaggerated it enormously, it had also introduced the concept of an ‘all-island economy’ which did not and does not exist, as shown by a recent Policy Exchange report ‘The island of Ireland: two distinct economies’.

While there was an ongoing mapping exercise to establish the full extent of north-south cooperation’s reliance on alignment with common EU law and policy, there would be no corresponding mapping exercise to establish the implications for the EU’s Protocol solution on east-west cooperation, a major failure of care.

The UK government was taken by surprise by this. Desperate to get into the next phase of talks on the future of the UK-EU relationship, the UK effectively accepted the EU’s argument, but it did push back by making the EU’s solution an insurance policy – the ‘backstop’. This would only kick in if a solution could not be found or could not be found before the UK left the EU, through either the future UK-EU relationship or alternative specific solutions. This was set out in the Joint Report of December 2017:

The United Kingdom remains committed to protecting north-south cooperation and to its guarantee of avoiding a hard border. Any future arrangements must be compatible with these overarching requirements. The United Kingdom’s intention is to achieve these objectives through the overall EU-UK relationship. Should this not be possible, the United Kingdom will propose specific solutions to address the unique circumstances of the island of Ireland. In the absence of agreed solutions, the United Kingdom will maintain full alignment with those rules of the Internal Market and the Customs Union which, now or in the future, support north-south cooperation, the all-island economy and the protection of the 1998 Agreement.

May believed she had squared the circle of Brexit on the island of Ireland, but she hadn’t. She had given the EU a legal obligation – albeit as an insurance policy. Unfortunately, the EU had no interest in settling for alternatives to that insurance policy as it gave it all that it wanted; the EU-UK relationship could not provide the frictionless trade without the UK’s continued membership of both the customs union and the single market – something May was strongly opposed to and which the UK had made clear before and during the negotiations. Specific solutions to avoiding a hard border were subsequently dismissed by the EU too. The Joint Report’s language masked the reality that only the ‘backstop’ would work for the EU and, as Michel Barnier made clear at the time, that ‘backstop’ would involve NI-only alignment.

It was only at the end of February 2018, when the EU published its draft of the Withdrawal Agreement, that the UK government pushed back – but too late. May spent most of 2018 trying to find a customs and regulatory arrangement that would allow a UK-EU relationship to solve the Irish question, supported by those who wanted a very close economic relationship with the EU. Chequers, however, which proposed a free trade agreement between the EU and a UK that aligned with Brussel’s rulebook, was exactly what the EU wouldn’t accept. May should have known this; perhaps the prize of achieving all the UK’s aims was just too alluring for the oft-stated EU position to intrude. It was a pity, because all the remaining negotiating time was wasted. By October 2018 the UK was negotiating a temporary arrangement that did not solve the Irish question but rather pushed the hard decisions a little further down the road. May’s deal was a salvage operation that neither produced the Brexit that May had set out in her key speeches nor solved the Irish problem and which in consequence couldn’t pass parliament, except with a resolution of the ‘backstop’, a resolution she tried to find but to no avail.

The resolution that Johnson was able to negotiate faced the reality of the UK’s options: the ‘insurance policy’ became permanent and Brexit was delivered on her original terms as set out at Lancaster House, with the compromise of checks, not a border, on the Irish Sea. The challenge of managing a complex and ill-thought though EU ‘solution’ remained. The Johnson government believed that the assurances on the UK internal market, including minimising checks, that were set out within the Protocol, as well as its commitments to the Good Friday Agreement, would mean that the level of checks would be proportionate to risk. In addition, they had negotiated the concept of ‘goods not at risk’ of entering the Single Market. Johnson had crucially managed to get consent built into the agreement, thus addressing to a great degree the democratic deficit.

Problems of implementation showed themselves once the Protocol’s trading arrangements had to be implemented and the UK swiftly introduced grace periods to allow business to prepare and then extended them to secure both economic life in Northern Ireland and stability too. Meanwhile, the EU insisted on full implementation of the Protocol as the only way to solve the problems that Brussels itself was causing, a position it finally abandoned last summer in the face of reality. The Commission then put forward a set of proposals that only met in part some of the problems on trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and which failed to address the political problems exemplified by the rejection of the Protocol by all unionist parties. While the original operational problems of the Protocol remained, the really significant issue had become political: the Protocol had been advanced by the EU as a political solution and it was failing as a political solution. With the EU refusing to address this political failure, and insisting on only technical fixes, the talks were at an impasse.

In February 2022, Northern Ireland’s First Minister, the DUP’s Paul Givan, resigned over the Protocol, bringing about the collapse of the executive and an even deeper political crisis. Following last month’s elections, unionist opposition to the Protocol has led to their refusal to allow the restoration of the devolved government and legislature. The Protocol, devised by the EU to create a political solution to the challenge of Brexit on the island of Ireland, has now failed not only on the basis of the UK’s assessment but on the basis of the EU’s own Guiding Principles. The Protocol has failed the EU’s own negotiating guidelines and negotiating directives.

The EU had insisted a solution had to ensure that ‘nothing in the Agreement should undermine the objectives and commitments set out in the Good Friday Agreement in all its parts and its related implementing agreements’. When the EU was confronted with the east-west realities of the Good Friday Agreement, it ignored them. Then it set out a stronger north-south response as well as saying the solution would have to ensure the continued operation of the institutions established by the Good Friday Agreement. Of those institutions, strand one, devolved government, has collapsed because of the Protocol; strand two’s institution, the north-south Ministerial Council, cannot operate without the executive and Assembly. It has been quite an achievement; overshadowed by British self-doubt and division – as well as the clear recognition of our own failures over the resolution of this complex issue – we have failed to grasp the enormity of the EU’s own negotiating failure. And so have they.

The Commission was tasked by the member states to engineer a solution that protected the three strands of the Good Friday Agreement and secured the integrity of the EU’s legal order. The single market has been protected 100 per cent; the Belfast Agreement is on its knees.

The Protocol exists to secure four objectives, set out in its first article: ‘This Protocol sets out arrangements necessary to address the unique circumstances on the island of Ireland, to maintain the necessary conditions for continued north-south cooperation, to avoid a hard border and to protect the 1998 [Good Friday] Agreement in all its dimensions’. It is presently achieving only two of them: avoiding a hard border and north-south cooperation. It has not only failed to achieve the other two objectives, it has also directly placed the Good Friday Agreement in dire peril. In doing so, it is not only the Protocol that has failed: the Commission has failed to discharge its mandate from the European Council.

The current position that the mandate may not be reopened needs to be seen in the light of its legal and political status: a mandate that has not been fulfilled and a Commission that failed to deliver a political solution as directed. The idea that a solution could be set down on a piece of paper, without any real-world testing of its effects and unintended consequences, while its authors turned a blind eye to the economic and political realities of Northern Ireland, was always likely to end in failure.

And so here we are. The Commission will find it difficult to own such a large-scale error; it will not be easy to go to the Council and explain that its solution to the problem of Brexit has become an existential threat to the Good Friday Agreement, the international treaty it was tasked with protecting above all else. The Council and its members should be under no illusions that just blaming the Brits for this crisis misses the mark; their mandate has been failed by the Commission blatantly ignoring the complex realities of Northern Ireland, not least the fact that its political, economic and cultural life is far more integrated into the UK than it ever imagined. The Council and its members can no longer – and must no longer – hide behind the Commission; they need to hold the Commission to account, reopen the mandate, and work with the UK to find a solution that respects the east-west realities of the Good Friday Agreement and Northern Ireland’s place in the UK.

Comments