It’s surprising how many perfectly good bridge players lack confidence when it comes to squeeze plays. They seem to think a squeeze is some sort of dark art which experts alone can master — a view no doubt reinforced by all that technical jargon about ‘rectifying the count’ and ‘isolating the menace’. But the truth is that many squeezes are within any reasonable player’s grasp — in fact, even beginners have a chance of executing one simply by playing off all their winners and hoping for the best.

My favourite example of a near-beginner pulling off an intricate squeeze by fluke was shown to me some years ago — I forget declarer’s name, but I’d like to take this opportunity to wish all Spectator readers at least one hand like this in the new year:

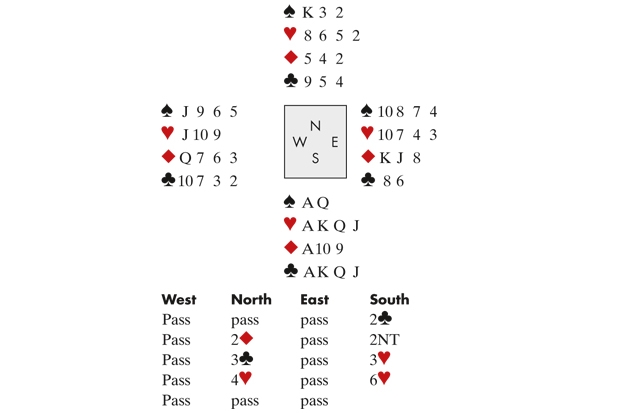

West led the ♦3 to East’s ♦K and South’s ♦A. South drew trumps. When they split 4–1, she could count only 11 tricks: the ♠K was stranded in dummy. She cashed her winners, coming down to ♠Q ♦109 opposite ♠K3 ♦5. Next she played the ♠Q and exited with the ♦10. West won with the ♦Q, East’s ♦J fell under it, and West’s last card was a diamond which went to South’s ♦9 — slam made!

As it happens, E/W were experts so they could explain how they’d been squeezed. In the three-card ending above, one defender had to keep two diamonds or she could simply concede a diamond: the other had to keep two spades or she could overtake the ♠Q with the ♠A and cash the ♠2. So when she cashed the ♠Q and exited with a diamond, if the opponent with honour-doubleton won, their honour would swallow up their partner’s (as had happened); and if the opponent with just one diamond won, they would have to play their last card — a spade — to dummy’s ♠K. And that, by the way, is what’s known as a ‘stepping-stone’ squeeze.

Comments