Do you ever watch the greats playing bridge? And if you do, are you sometimes baffled, because instead of playing the obvious card, they do something that seems to be completely random? Of course, it never is random — it’s just that they are operating on a different plane from the rest of us. Not only is their awareness deeper and their technique better, but they never lose sight of the psychological aspect of the game. They are always trying to see things from their opponents’ points of view, to entice them to defend in a way that will bring about their own defeat. As John Lennon once said, you have to be a bastard to make it to the top.

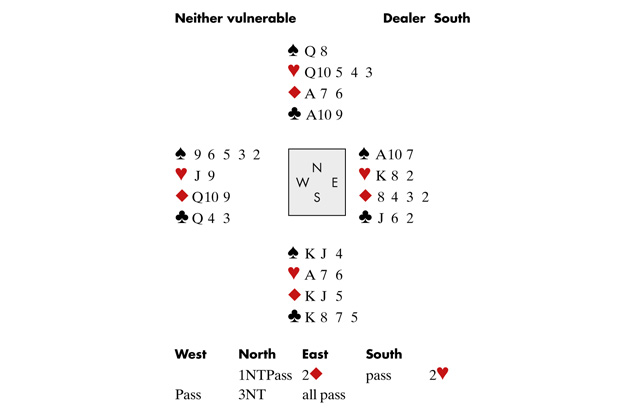

This hand comes from the recent final of a US Championship. Zia Mahmood was South:

West led a spade. East won with the ace and returned a spade to Zia’s king. If spades divide 4–4, you can afford to lose hearts twice, to either opponent. But if they divide 5–3, you could be in trouble: if East gets in to play a third spade while his partner still has a heart winner, you’re down.

At this point, one of the commentators predicted that South would cash the ♥A and then play low towards dummy, hoping that an honour would appear on his left, and if not, he would have to make a good guess whether to put up the ♥10 or ♥Q. Zia, however, crossed to dummy’s ♣A at trick 3, and played a low heart. Look at the pressure East was under: suppose South held ♥Jxx — West would take the ♥J with his ♥A, and if he continued spades, East would have none to return when he got in with his ♥K. And so East hopped up with his ♥K to preserve his partner’s ‘late entry’ — enabling Zia to make all the hearts and 11 tricks.

Comments