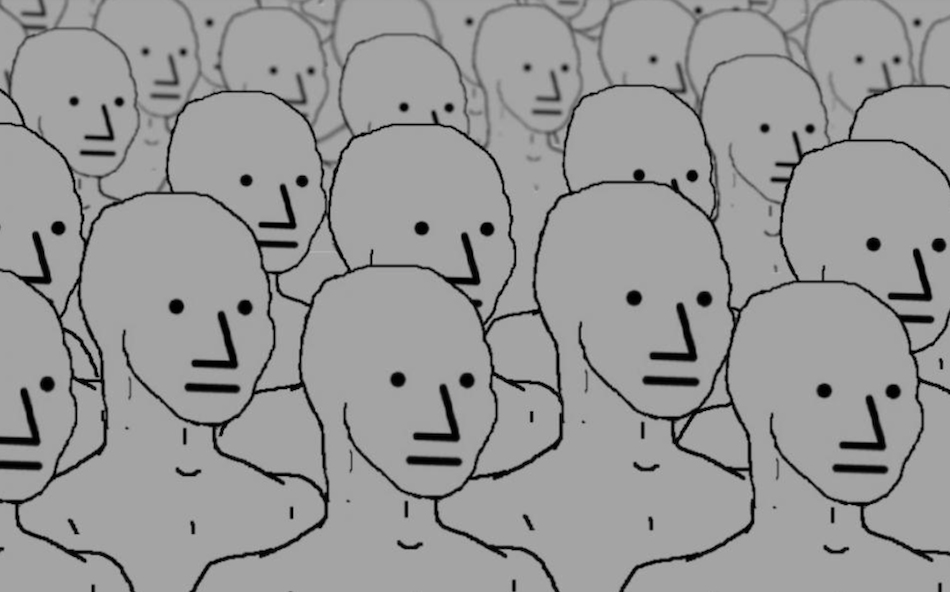

The Cambridge Dictionary defines ‘normie’ as ‘a normal person, who behaves in the same way as most other people in society’.

Merriam-Webster tells us it refers ‘to one whose tastes, lifestyle, habits, and attitude are mainstream and far from the cutting edge, or a person who is otherwise not notable or remarkable’.

Oh, how I miss normies. Flicking through the streaming channels recently, I took a swerve from Domina and The White Lotus – both excellent – and found myself rewatching two old British sitcoms, Sykes and Duty Free, for the first time since their original transmissions. (Duty Free and The White Lotus are strangely similar in some regards, if you squint a lot, both being concerned with the change in sexual behaviour that occurs when people book into sun-kissed hotels.)

I’d written them off in my mind as lightweight and corny. And yes, they are lightweight, but they’re inventive and insightful too. But the big difference is that – unlike modern TV – the characters, settings and writing are all hardcore normie.

Sykes is about a brother and sister who share a house. That’s the concept – that’s it. They have a snobbish neighbour. The stories are about things like being reluctant to kill a mouse, refereeing a local football match, hiring a riverboat. Duty Free is about two married couples on holiday in Marbella, the husband of Couple 1 tempted to have a fling under the sun with the wife of Couple 2. That’s all.

Where have all the normies gone? Even the bread-and-butter soaps and hospital/police dramas of today are filled with outlandish characters and situations. There is yet another serial killer currently on the loose in Coronation Street; the half-brother of poor Gail Platt, who was married to another serial killer not so very long ago. Between these events her daughter-in-law was knifed on the cobbles, although not before she’d clubbed her ex-boyfriend to death and buried him under Gail’s patio.

The curse of ‘representation’ recently saw a character in Casualty cheerfully announcing to her coworkers that she was going in for a double mastectomy, to which news they barely turned a hair. And these are the terrestrial, everyday stories of ordinary folk. The global (for which read American) series are packed with the disturbed, the mega-wealthy, and the bizarre. Not Going Out and Two Doors Down remain, but they are old brands and even they are full of eccentrics and oddballs.

The last remaining bastion of normieness on TV are the bits in quiz shows Pointless and The Chase where the contestants introduce themselves.

I used to find these interludes monotonous and irritating; now I treasure them as oases of sanity. When someone called Emma from Dundee reveals that she’s a receptionist at an opticians’ with two kids and a husband called Doug, I want to cheer.

When ABBA released their new album in 2021, the subject matter of the songs – a nice family Christmas, regrets about divorce, a happy return to the small town of your birth – were a positive balm. Despite the murders that form its backdrop, Channel 5’s recent Madam Blanc – based around a tentative romance between two utterly ordinary people – feels dangerously seditious in our age.

These are the people we encounter in real life all day every day. But they are not ‘represented’. There are no organisations advocating for the inclusion of normies, and yet – in our high-concept culture – we hardly ever see them.

For people like me, normie culture served a function as vital orientation

As something of an oddity myself growing up – or so I was always being told, and this was back in the day when it was, believe me, never a compliment – I feel for similar incongruous souls reaching their maturity today. In the time of Sykes and Duty Free I got to feel excitingly countercultural. When strangeness is the prevailing ideal, when status points are accrued, not lost, from being socially awkward or not entirely heterosexual, how much more of a struggle it must be to hold on to your individuality and self-worth. I can’t begin to describe how much more thrilling it was to be ‘different’ when people weren’t forever throwing parades for you, and were showering you with dirty looks and raised fists rather than plaudits and apologies.

For people like me, normie culture served a function as vital orientation. You need a normie world to exist alongside, to provide you with a firm footing. You need meat and potatoes; a plate of salt and pepper is no meal at all.

Now the contagion has spread so that even former normies have gone rogue. Carol Vorderman has switched from undisputed Normie Queen to student union bar polemicist. Previously anodyne TV personalities like Kirstie Allsopp have suddenly de-normied, posting bizarre interventions on gender or comparing the new Twitter logo to a swastika. Two of the greatest normie exemplars, Philip Schofield and Huw Edwards, have turned out to be not very normie at all.

Such is our de-normified culture that even these transformations haven’t come as particularly enormous shocks. If Judith Chalmers had launched herself into a massive, four-letter strewn attack on the poll tax in 1990, or if Wogan had angrily snapped that a woman could have a penis in 1986, the nation would have been struck dumb.

As it stands, the sight of normies is now a shock – whether it’s exasperated drivers ripping banners from the hands of Just Stop Oil, or the provincial high street vox pops where people don’t just regurgitate received 2023 London opinions.

We need to see normies, or we get a very skewiff impression of life and of politics. We forget them at our peril. Because, without them, what the hell are we?

Comments