Yesterday, thousands of runners in the London Marathon converged on the greatest target in the world. Winston Churchill was the first to see the problem. ‘With our enormous metropolis here… [we are] a kind of tremendous fat cow, a valuable cow tied up to attract the beasts of prey,’ he told the Commons in 1934. But ‘we cannot possibly retreat, we cannot move London.’ New enemies, from the IRA to al-Qa’eda, have come to do their worst — but since the London Underground bombing of 7 July 2005 none has succeeded. The average British urbanite would be forgiven for thinking the threat has subsided. It has not.

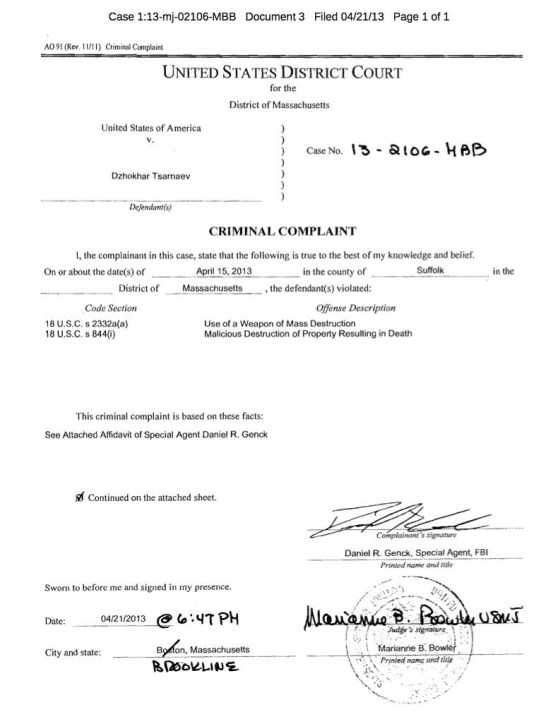

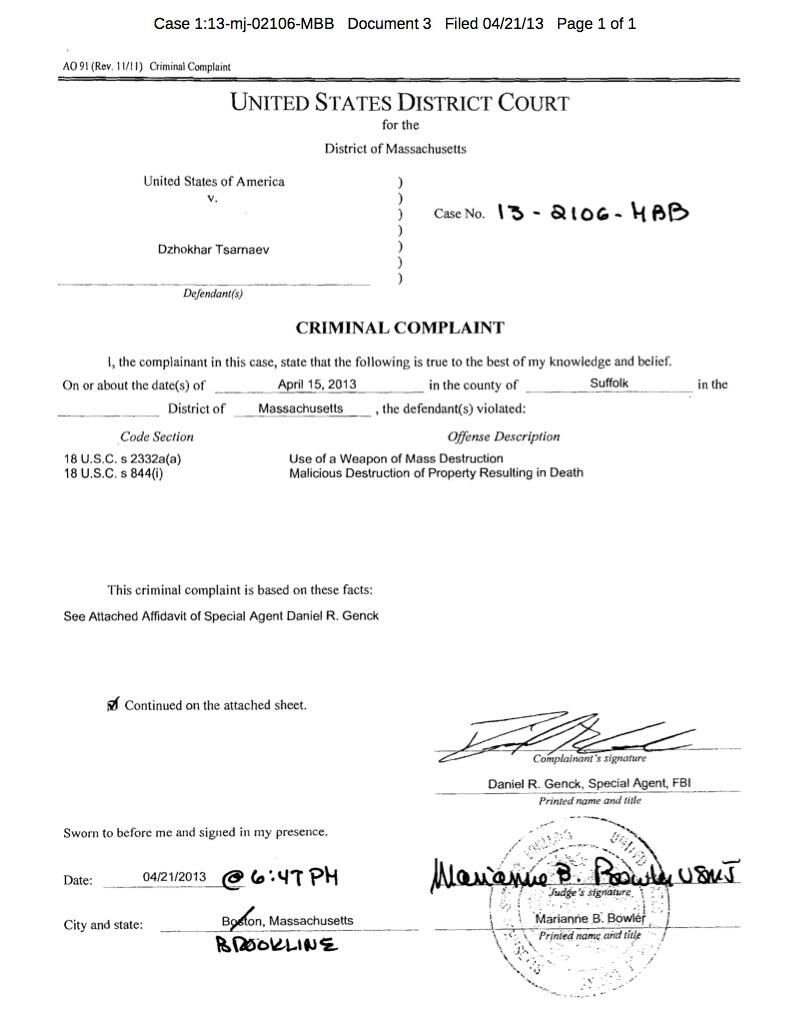

The atrocity at the Boston Marathon last week is a reminder that such threats never vanish — they just get intercepted. Most of the time. As the IRA put it after the Brighton bomb, ‘remember we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always.’ The best minds in counter-terrorism would struggle to detect two bombs made from explosives packed in ordinary kitchen pressure cookers and hidden in rucksacks. The FBI is under criticism because it had been tracking the man who has just been charged with the attack, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (right). But the Feds faced the problem that MI5 does all the time: when to swoop? Move early, and you have no evidence. Too late, and the bomb explodes.

cookers and hidden in rucksacks. The FBI is under criticism because it had been tracking the man who has just been charged with the attack, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (right). But the Feds faced the problem that MI5 does all the time: when to swoop? Move early, and you have no evidence. Too late, and the bomb explodes.

Our security services face this conundrum far more often than is commonly believed. Jonathan Evans, the director-general of MI5, said in a speech last year that ‘Britain has experienced a credible terrorist attack plot about once a year since 9/11’. The Royal United Services Institute keeps a record of potential terrorist plots on British soil and counts 43 since the Twin Towers were struck. Some of the interceptions, such as the thwarting of the Heathrow airport plot, have been nothing short of spectacular – but they never seem that way, because the end result is that nothing happens.

Years of improving intelligence, infiltration and drone strikes have allowed the West to win the battle with al-Qa’eda. Osama bin Laden is dead, his group’s leadership in Afghanistan has been decapitated and the net is closing on the biggest single threat: the al-Qa’eda franchise in Yemen which was behind both the US-bound underpants bomb and the printer bomb found in an East Midlands airport. The Islamists in the Sahara desert, against whom David Cameron recently promised to fight a ‘generational struggle’, do not seem to reciprocate his attention and have at present no overseas ambitions. The era of global terror networks appears to be drawing to a close.

But attacks still come. Only last week, the final members of a Birmingham terror cell were found guilty of plotting to detonate eight bombs in the city. One of them, Irfan Khalid, had boasted that he wanted to create ‘another 9/11’ — we know this because the security services had somehow bugged his car. Both British and American security services have seen a sharp fall in would-be jihadis flying off to Pakistan to train, now that the chances of interception are far larger. There is more evidence of them following advice from the now-dead leader of al-Qa’eda in Yemen, Anwar al-Awlaki: do it anyway, tell a minimal amount of people. This is an admission the idea of a global terror network is not really viable, when the security services can no successfully infiltrate the hierarchy of these jihadis.

So how seriously should we take such exhortations? So what if the jihadis publish an online terror magazine (called Inspire) and advise would-be jihadis: just do it? The threat of improvised Islamist attacks is serious enough to have inspired the Birmingham plotters. And it resulted in precisely what we saw in Boston: smaller, cruder bombs. Self-radicalisation is of course far harder to track, especially if the chemicals are being extracted from sports injury cold packs (as was the case in the Birmingham plot). It now appears that Tsarnaev was radicalised in precisely the same way.

As the threats change, the security services change with it. A few years ago, three in every four people being traced by MI5 were linked to Pakistan or Afghanistan. Now this is fewer than one in two. It is not just the rise of Africa-based terror groups but also the rise of home-grown enemies within. Developments in Northern Ireland, where the splinter groups have splinter groups, show that the Republican threat is evolving rather than dying. The renewed focus on so-called ‘lone wolf’ attackers is the latest trend in terrorism.

This is not limited to jihadis. In the immediate aftermath of the Boston attack there was speculation that it could be the work of an American — similar to Timothy McVeigh, whose Oklahoma truck bomb was the biggest terrorist incident the US had experienced until 9/11 — then the British may draw the incorrect assumption that such madness could not happen here.

Norway had no history of this, until Anders Breivik struck. There is already evidence that the disintegration of the British National Party has pushed people to violent extremes. The London nailbomber, David Copeland, was an ex-BNP member who wanted to advance a lunatic idea of racial purity. So yes, al-Qaeda is debilitated and leaderless. But the lone wolf terrorist, using the internet to self-radicalise, is fast becoming the new threat.

This is an edited version of the leading article of the current issue of The Spectator.

Comments