Philippe Sands’s compelling new book opens in 2018 at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, where Liseby Elysé – ‘a distinctive lady dressed in black’, who can neither read nor write – is making a video statement before 14 judges. In Creole, she describes how, in 1973, she and the last of her 1,500 fellow islanders from Peros Banhos (part of the Chagos archipelago, south of the Maldives) were forcibly deported to Mauritius. They were herded in the dark onto a boat for a four-day passage, with neither notice nor explanation given, restricted to one wooden trunk of possessions apiece, homes abandoned and all their pets rounded up and gassed. The boat’s captain said he had ‘never transported people in such terrible conditions’. Mme Elysé was four months pregnant, and later lost her child.

The author, a distinguished academic and barrister, then took to the podium, acting for the Mauritian government, and argued that this removal was illegal, as was the original British severance of the islands to set up a new colony in 1965, the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), which is the subject of this succinct, impressive work. And it’s not some retrofitted anticolonial story, either: the matter is very much current, and unresolved.

For most of us, if we’ve heard of the Chagos at all it will be because of its militarised atoll of Diego Garcia, which became the site of a US base in 1971, nicely named Camp Justice. The first aircraft to land carried Bob Hope and a troupe of fellow entertainers. Later (after half a billion dollars had been spent developing it), the island apparently became a CIA ‘black site’ and part of the post-9/11 rendition system. Then, in 2003, it was the launch base for initial air strikes against Iraq.

‘I am not an independent observer,’ writes Sands. His own involvement with international law is one of the key elements of this saga, which has origins in the 1940s with the United Nations Charter, the setting up of its General Assembly and the new ICJ. Decolonisation and the treatment of ‘non-self-governing territories’ became a vital issue; and, as it had been at the Nuremberg trials, deportation was classified as ‘a crime against humanity’. (Two of the author’s great-grandmothers, each with a single suitcase, were deported by the Nazis and perished; his mother was a child refugee.)

When the European Convention on Human Rights was drawn up in 1950, Britain specifically excluded Mauritius from the list of colonies to which it applied. In 1953, the year Liseby was born, Sir Hilary Blood was the governor of what he termed his ‘pocket handkerchief paradise’. She recalled a happy, religious island upbringing: ‘We had everything we needed.’

The islanders were herded in the dark onto a boat, restricted to one wooden trunk of possessions apiece

With the deftness of marquetry, Sands lays down the groundwork of international law and its evolution during the Cold War, when he believes both Britain and America were selective and hypocritical in their attitudes toward UN policy. This particularly applied to the 1960 Resolution number 1,514, a few paragraphs about the granting of independence, which asserted: ‘All peoples have the right to self-determination.’ Both countries, which were covertly discussing security issues, abstained. So, when Mauritian independence was being negotiated, the strategic potential of Diego Garcia was kept secret, though the detachment of Chagos as part of a new BIOT colony was part of the deal.

Anticipating international criticism (not least disapproval from the UN, which was ignored), Britain falsely claimed that there was no ‘permanent population’ on the islands, which would have been puzzling news to the Chagossian diaspora that ensued. It is still unclear why we insisted on deporting the inhabitants of the entire archipelago, since the US only required the clearance of Diego Garcia itself. There has never been an apology. When he comes to discuss the Falklands, Sands unavoidably concludes: ‘One rule for whites, another for blacks.’ If there is an alternative interpretation, I’m sure Spectator readers would be interested to hear it.

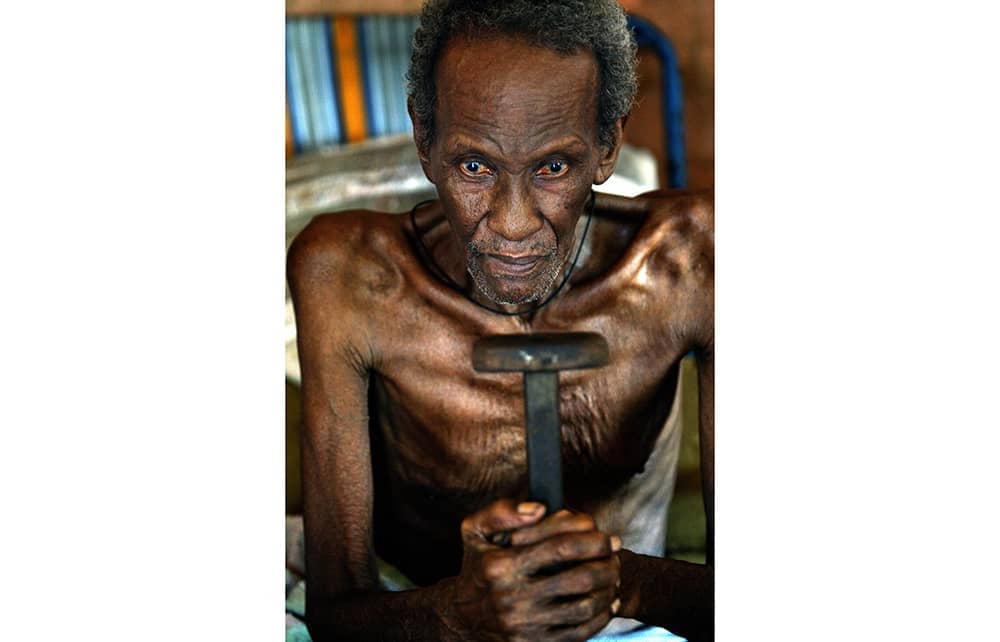

One of the many merits of this intriguing account of how the case against Britain was finally brought to The Hague is its human focus (enhanced by Martin Rowson’s grand guignol illustrations), and the author’s emotional restraint. His indignation occasionally burns through into sarcasm, but the overall tone is steely. Despite the eventual ICJ ruling that Britain had acted unlawfully, all requests for resettlement have been resisted. Precious little of the promised compensation has been paid. It is probable that the government is looking for a way to back down without loss of face, but this continued intransigence seems shameful.

Earlier this year, Mme Elysé and some others revisited Peros Banhos for five emotionally charged days. Sands was of their party, and on the last page allows himself to write: ‘I find it hard to repress the sense of fury at the wrongs that have been done here.’ Yet you feel he has done the islanders proud.

Comments