This pandemic has not been short of unexpected twists. Perhaps the most surprising of them all has been Britain’s willingness to close its schools. Boris Johnson’s reasoning for his U-turn in January seemed paradoxical at best: despite judging schools ‘safe’, he closed them anyway. Even more incredibly, the bulk of British parents have been supportive of his decision. On this issue, at least, is it time to take our lead from Europe?

While Britain has outpaced Europe in its vaccine roll-out, the attitude towards schooling on the continent has been much bolder than our own. Schools have remained open in both France and Spain throughout the winter, despite both countries experiencing a spike in Covid cases. What’s more, cases are now levelling off in both countries. It remains to be seen whether this plateau continues and if the existing lockdown measures are enough to contain the virus.

But it’s not as if France and Spain are contravening the science by keeping schools open. They are simply following the advice of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control which concluded that schools do not play a major role in the transmission of Covid-19 – science that Downing Street would do well to heed. Indeed, these findings are backed up by a study published on Monday by two of the government’s own scientific advisors that also found that infections in schools lagged behind those of the rest of the community. While the British study was less conclusive, the government needs to face up to the fact that no data is going to make the decision for them and that some risks need to be taken. Professor Mark Woolhouse of Edinburgh University who sits on a SAGE sub group specifically cited the example of Europe today as a reassurance that schools posed a low risk of increasing rates of infection: ‘One of the stated reasons for keeping schools closed was to avoid some surge in cases when they open – that’s never happened across western Europe,’ he told the Science and Technology Committee. ‘We know what a surge in cases looks like – we saw it in September and October in the universities, we’ve never seen that in the schools, and I don’t expect to.’

Even if cases do rise again in France and Spain, their stance on schools is backed by a strong ideology that has been sorely missed this side of the Channel. Their reasoning goes beyond case numbers. There’s an overwhelming sense from both governments that children’s education should be prioritised, and that risks should be taken in order to protect it.

French Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer summed up the differing French approach in the autumn: ‘Not everything should be destroyed by the health situation,’ he told France’s Journal du Dimanche newspaper. It’s this sort of ideological drive that Britain is missing.

The French sentiment was echoed by the Spanish epidemiologist Quique Bassat who said that Spain was right to open schools: ‘As long as we can’t prove that we are exposing [children] to a greater danger than we are aware of to date, or that they cause an increase in community transmission, I think we should remain firm about keeping schools open.’

He couldn’t have articulated a more polar opposite approach to the UK if he had tried. The British government seems to have taken the view that unless the scientific evidence can categorically prove that schools don’t spread Covid, then the default policy should be to keep them closed.

In France, there is fierce support from parents for school attendance. 79 per cent of French parents were in favour of schools reopening in the autumn. Compare this to Britain where, back in August, 56 per cent of parents surveyed by Ipsos Mori thought it would be acceptable for children to be home-schooled for the long term. Astonishingly, this was actually a higher percentage than the population at large (49 per cent).

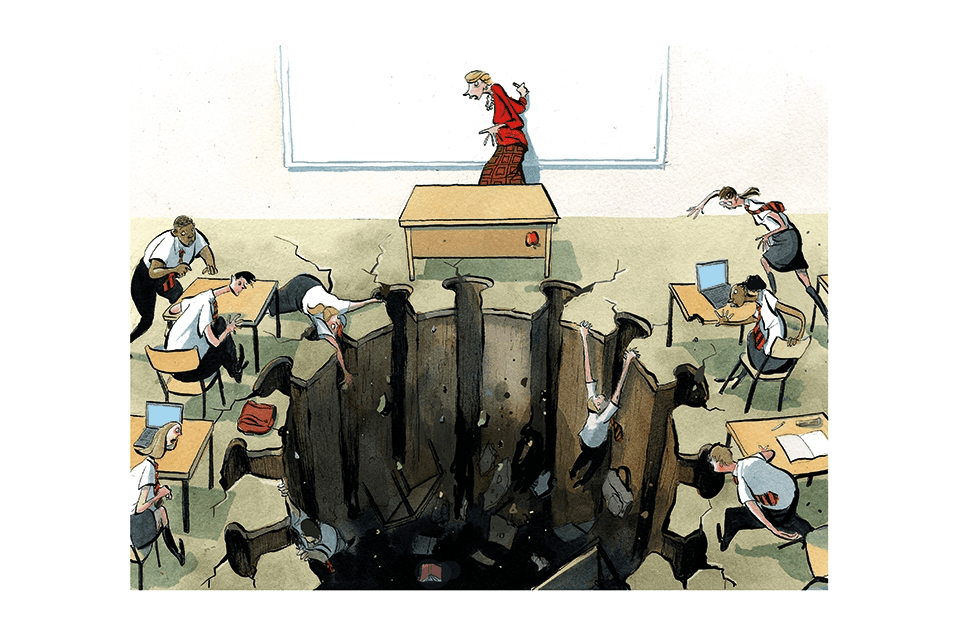

Britain’s teaching unions too have been vocal in their opposition to reopening schools, and have demanded national closures. In contrast, when French teachers in Paris went on strike for a day in November, they were simply calling for increased hygiene measures. That schools would do their utmost to stay open was a given. What sort of topsy turvy world are we living in when the British unions outdo the French?

Given the growing volume of evidence about the safety of schools, there should be no hesitation about them reopening on March 8th. But much of the damage caused by school closures could have been prevented if we’d shown the same courage as our continental friends and acted in the interests of children from the beginning.

Comments