Sir Keir Starmer has vowed to ‘reset’ the United Kingdom’s relations with the European Union. But at what cost? The EU has reportedly set out part of the price the UK might have to pay to be allowed back into its good books: Brussels wants Britain to contribute to the EU’s defence missions.

Foreign Secretary David Lammy travelled to Luxembourg this week to a meeting of the EU Foreign Affairs Council to address the issue of security – an important element of Starmer’s intended ‘reset’. In Monday’s meeting, the EU reportedly pressed the Foreign Secretary for UK participation in its peacekeeping and conflict prevention missions, of which there are currently more than a dozen.

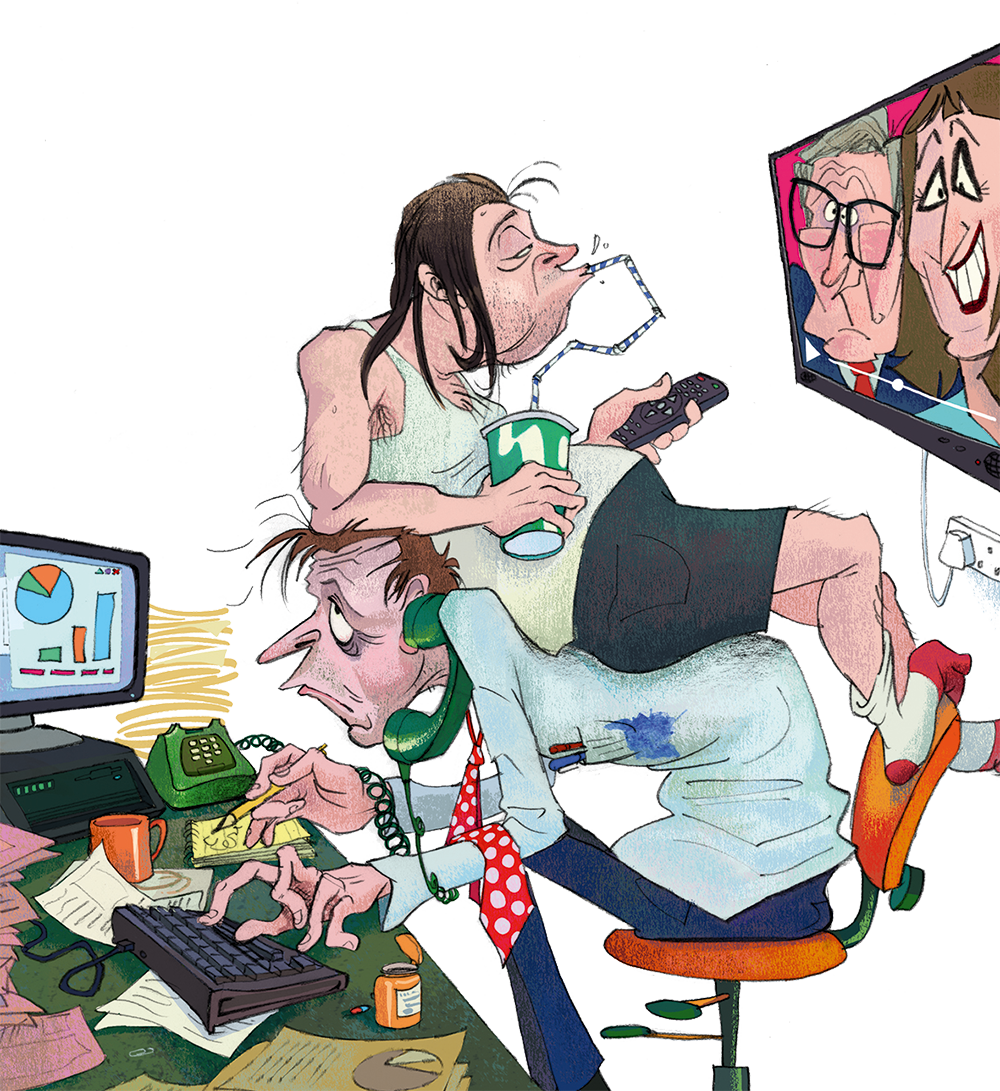

It would be interpreted in Washington as a slap in the face

Brussels has indicated unofficially that this would be an easy way for the UK government to begin negotiating one of its manifesto commitments, ‘an ambitious new UK-EU security pact to strengthen co-operation on the threats we face’. But this is a hazardous project: the EU’s defence capability is weak and fragmented. Attempts to strengthen it are also likely to undermine Nato, the cornerstone of the UK’s defence policy.

Despite the existence of an EU common security and defence policy, military matters remain largely the preserve of member states. Article 42 of the Treaty on European Union draws relatively tight constraints around defence policy, and notes that some members ‘see their common defence realised in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’. This is an understatement: of the 27 EU member states, only four – Austria, Cyprus, Ireland and Malta – are not also members of Nato, and in military terms they are all minnows with a combined active strength of under 50,000.

The Brussels bureaucracy is eternally ambitious, however. The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, has nominated former Lithuanian prime minister Andrius Kubilius for a newly created defence and space portfolio when the college of commissioners is confirmed next month. This follows the publication earlier this year of a European defence industrial strategy intended to increase collaboration, investment and readiness in defence procurement in the bloc.

This is a direction of travel the UK must not encourage, let alone join. There is a simple truth which is often overlooked: military assets cannot be in more than one place at one time, nor committed to more than one mission. Nato is the primary framework of UK defence and security policy, and should emphatically remain so: 75 years old, it is the most successful alliance in the world and has well-developed command, control and planning functions. Critically, it engages the United States and forms a vital transatlantic bridge.

Countless words have been spoken and written about the challenges Nato faces, especially if Donald Trump is elected president of the United States for a second term in November. Trump distrusts the alliance on an elemental and instinctive level, seeing it, in his childlike, paranoid way, as an example of ill-intentioned foreigners taking advantage of American goodwill. However, his accusation that Nato’s European members do not spend enough on defence was fundamentally accurate. It is only this year that the majority are expected to meet the target of 2 per cent of GDP on defence (which was first proposed 20 years ago).

There could hardly be a worse response to Trump’s threat to potentially reduce US support within Nato than for the UK, having left the EU more than four years ago, to contribute scarce military assets and capabilities to EU missions. We know that the defence budget is under almost intolerable strain, major equipment programmes are years behind schedule, recruitment is utterly inadequate and the army’s professed ability to mobilise a division-sized war-fighting unit at short notice is a myth. There is no slack in the system.

What kind of message would our participation in EU missions send? Even sources in Brussels are saying that it would not be a critical part of a mooted security pact, but that they expect it is something that could ‘be done really quickly’. Yet it would be interpreted in Washington as a slap in the face. EU members like France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands which, despite apparent agreement, shamefully backtracked on supporting the US-led Operation Prosperity Guardian to protect maritime commerce in the Red Sea. Britain, on the other hand, stood shoulder to shoulder with the United States. Would this proposed change put such displays of solidarity at risk?

The Prime Minister must decide how vital he believes a security pact with the EU to be. Since we are already partners in a defence alliance with 23 EU member states, it is hard to see what concrete gains there would be in signing up, save for making our European neighbours like us. But to contribute scarce military resources to an organisation of which we are not even a member, when funding and assets are at the centre of Nato’s immediate challenges, would be nigh on unforgivable.

Comments