We live in a strange era in which much of our day-to-day experience is constructed for us digitally on a screen. Even in the ‘real’ world, many objects that inhabit our homes will have been designed on a screen, made by computerised machines, and have that flat, wobble-free digital aesthetic – not only electronics, but furniture, tableware, toys, clothes and books.

It is probably impossible to resist this digital colonisation of our physical space altogether but, in some cases, there is an antidote: choosing objects that have been designed and made by hand, or by tools intended to assist humans rather than replace them. I am not talking about fine art but about ‘applied’ or ‘decorative’ arts and crafts, the products of small businesses or makers.

Antique furniture, say, or glassware objects have an intrinsic connection to the people who made them, and to a knowledge that has evolved over centuries. To watch a master glassblower and assistant make the arm of a chandelier, for instance, is to watch a virtuoso performance of precision, dexterity and speed; one that is supported by an arsenal of tools and explained with a complex technical vocabulary.

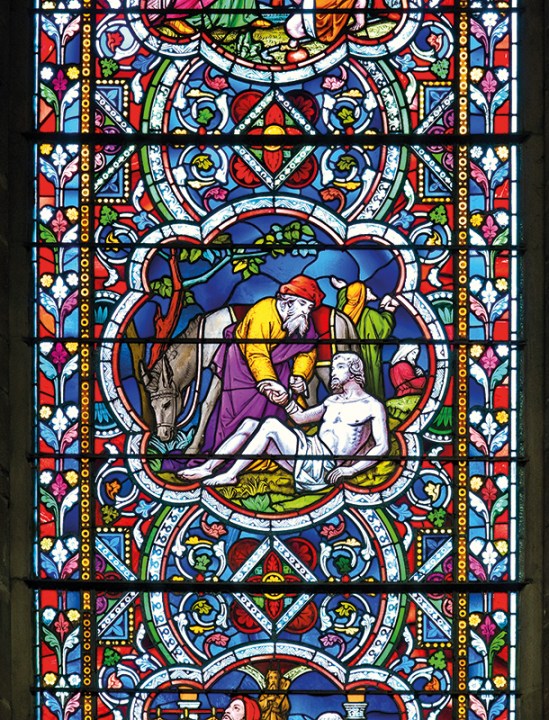

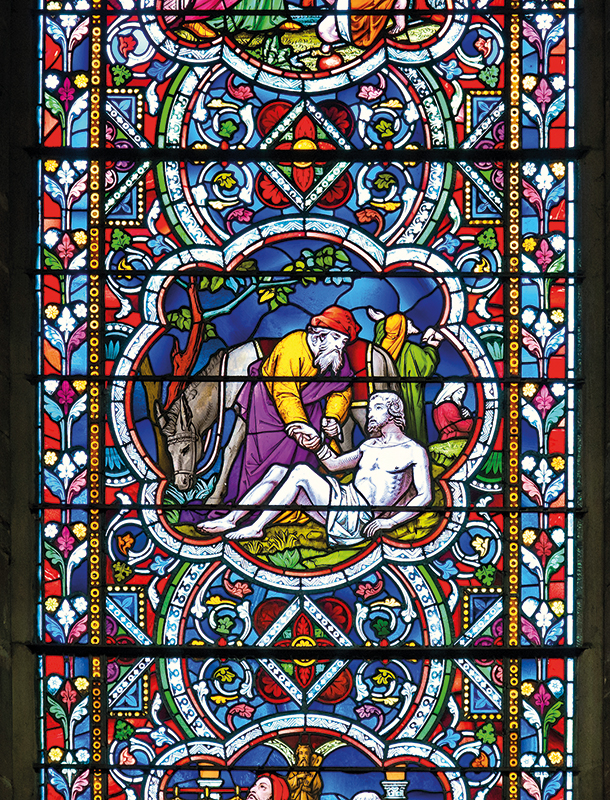

Britain’s own tradition of craftsmanship – from ceramics to glass, carpentry to watch-making – goes back a long way. The first stained glass in the country, for instance, was probably made in what is now Sunderland in ad 674. In recent decades, tertiary education in the applied arts, with its ties to industry and independent makers’ studios, has attracted students, scholars and practitioners from around the world. Unfortunately, for the generation now at school or university, the prospects of being able to receive sufficient education in a craft to make a career out of it seem increasingly limited.

For a number of reasons, whether to do with lack of funds or deliberate policy, art lessons have been slipping from the state curriculum in recent years. Unless they happen to have attended a school (usually independent) where art is still taught to a high level, many students have to start with basic skills when they enrol on an applied arts degree. As one lecturer told me: ‘A whole generation of students are coming through who do not know how to use their hands.’

Education in glassmaking faces particular threats. This is a shame, given the surprising success of Britain’s colourful subculture of glassmakers, designers, artists, gallerists, collectors, scholars and students. While the country has lost most of its former glassmaking factories, notably in post-industrial cities like Sunderland and Stourbridge, the past 50 years have seen the proliferation of studios run by independent glassmakers. And in contrast to much of the cultural sector, the British glass scene does not centre on London – except in terms of the galleries that exhibit and sell makers’ more expensive products.

But a practical concern for glassmakers today is rising energy costs – given that glass usually melts at upwards of 1,400˚C. The costs have hit practitioners hard, and many are struggling. Even more serious, however, is the post-pandemic closure of three of the country’s most important glass education institutions.

In 2022, the University of Wolverhampton – which had a renowned glassmaking programme linked to the industrial heritage at Stourbridge – suspended recruitment for 138 courses, including its BA in Glass and Ceramics; the suspension has now effectively become permanent. A year later, North Lands Creative, a studio and gallery in Scotland which offered courses and residencies, and had strong links to the international glassmaking community, was put into liquidation.

Meanwhile, the National Glass Centre – one of Sunderland’s most popular tourist attractions, the home of Sunderland University’s respected glass and ceramics department, and a magnet for local and international glassmaking expertise – is due to be shut down by the university next summer. Another venue has been touted as a partial replacement, but campaigners argue that it is too small and in a much less visitor-friendly location. The closure will represent a significant loss to the cultural life of the city, as well as to the future of glassmaking in Britain.

The disappearance of institutions like these, in the context of broader cuts to the arts and an apparent lack of political will to improve the situation, should be a warning. If young people are no longer being taught how to use their hands creatively, if we allow our lives to be dominated by the digital world, then we may lose crafts like glassmaking for good.

Comments