Britain has a widespread and collective mental health problem – but it’s not what you might think. Specifically, it’s that many people believe themselves to be mentally unwell when actually they are not. What’s more, society and the state have been prone to taking them at their word on this matter for far too long.

We’ve become aware of this unfolding problem recently as it’s evolved into a veritable crisis. It’s at once a financial crisis, one that now costs the taxpayer and the Treasury billions in welfare payments, while it’s also a still-evolving human crisis. We’re only now beginning to grasp the human cost of maintaining a mainly younger generation in a state of passive dependency, convinced that they are unable to deal with the necessary challenges of life – and all with the approval of those in authority.

Wokery helped to popularise and cement the notion that all opinions and viewpoints are of equal worth

We should then be grateful that the Conservatives have announced plans to tackle the immediate fiscal emergency at least. Helen Whately, the shadow and work and pensions secretary, says that those with common mental health conditions or some unremarkable behavioural patterns shouldn’t be receiving sickness benefits.

‘We cannot have a country in which one in four people believe they are disabled and believe that means that they should be receiving benefits from the state,’ she told Radio 4, ‘you shouldn’t be receiving sickness benefits if you have a common mental health disorder, something like anxiety, mild depression and some behavioural conditions like ADHD.’ She cited recent findings by the Centre for Social Justice that cuts in milder depression or anxiety could amount to £9 billion worth of savings.

Whately’s intervention is an audacious and wise one, but it won’t be widely welcomed. This is because some still believe our mental health crisis is entirely authentic. While most rational people recognise that the benefits system in relation to mental health is dysfunctional, in that there is a large proportion of loafers and chancers gaming the system, and welfare fraud is nothing new, there is an ever-growing percentage who now resort to state support because they sincerely believe themselves to suffer from debilitating mental disorders.

This latter development is genuinely new. While having or feigning physical injury or bodily impairment for financial indemnity is decades old, and one that can be subject to empirical testing or requires the application of deception, imagining yourself to be mentally unwell is often not subject to question, or even open to refutation. And it’s very much a novel, 21st century problem.

That we aren’t witnessing the recognition of previously undiagnosed or overlooked medical conditions, but rather a change in our culture, a social contagion akin to the previous profusion of transgender ideology, is obvious by the fact our ‘mental health crisis’ epidemic followed in the wake of the lockdown years of 2020-21. That was a time when the development and socialisation of so many young people were devastatingly interrupted. It was also the years of furlough, when a new generation learnt that it was acceptable to subsist on state hand-outs and not have to face working with other people for a living.

Yet the lockdown years were also visited on a generation fully in thrall to a therapeutic ethos of human fragility and now a burgeoning woke ideology. In drawing much of its intellectual ballast from the postmodern theory that knowledge is ineluctably relative, wokery helped to popularise and cement the notion that all opinions and viewpoints are of equal worth.

The notion that ‘perceived’ judgements are as valid as objective assessment had already passed into law in this country with the Crime and Disorder Act of 1998, which defined a ‘hate crime’ as, ‘Any criminal offence which is perceived by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice’. The primacy accorded to subjective perception, or ‘lived experience’, was subsequently elevated to new heights with the emergence of hyper-liberalism in the decades that followed, most conspicuously in the trans movement with the primacy it accorded to ‘gender self-identification’. This frequently became merely a verbal event that required no physical alteration, only a performative utterance.

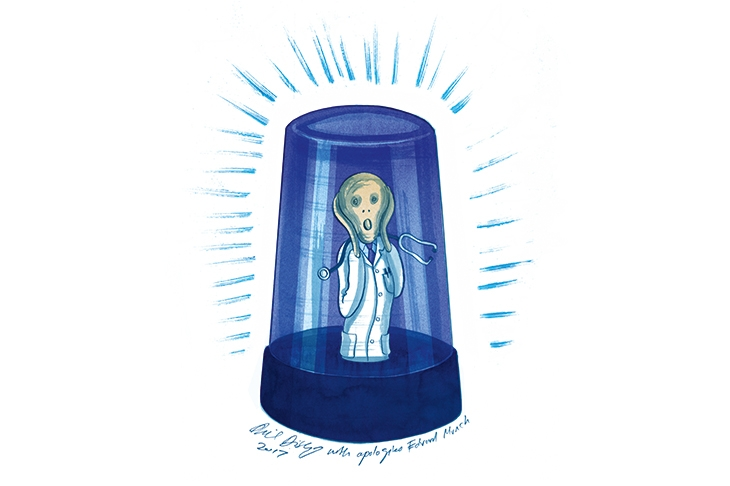

Our ‘mental health crisis’ is but the latest manifestation of a society beholden to the conceit that subjective personal testimony is on a par with objective evidence. Automatically believing those who protest that they have mental health or ‘neurodiversity’ issues – the latest examples being the TV chef Greg Wallace and Guardian journalist Owen Jones, self-proclaimed sufferers of autism and ADHD respectively – will hardly do anyone any good. Nor will doing so benefit those who suffer from clinical medical depression or youths with actual, severe learning difficulties and educational needs.

Our culture still cleaves to the notion that if someone believes something to be true, then we should accept it as true. Beyond making cuts right now, changing this mentality is the real challenge.

Comments