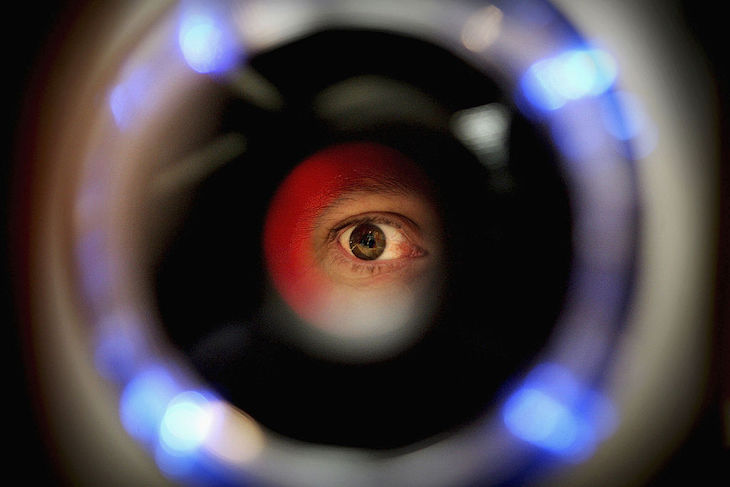

The vexed issue of compulsory ID is, once again, on the cards. ‘BritCard’ is being billed as a ‘progressive digital identity for Britain’ by Labour Together, the think tank that put forward the scheme earlier this month. The digital ID card has been endorsed by dozens of Labour MPs, and No. 10 is said to be interested in the scheme, which is being touted as a way to crack down on illegal migration, rogue landlords and exploitative work. But concerns about privacy appear to have gone out the window.

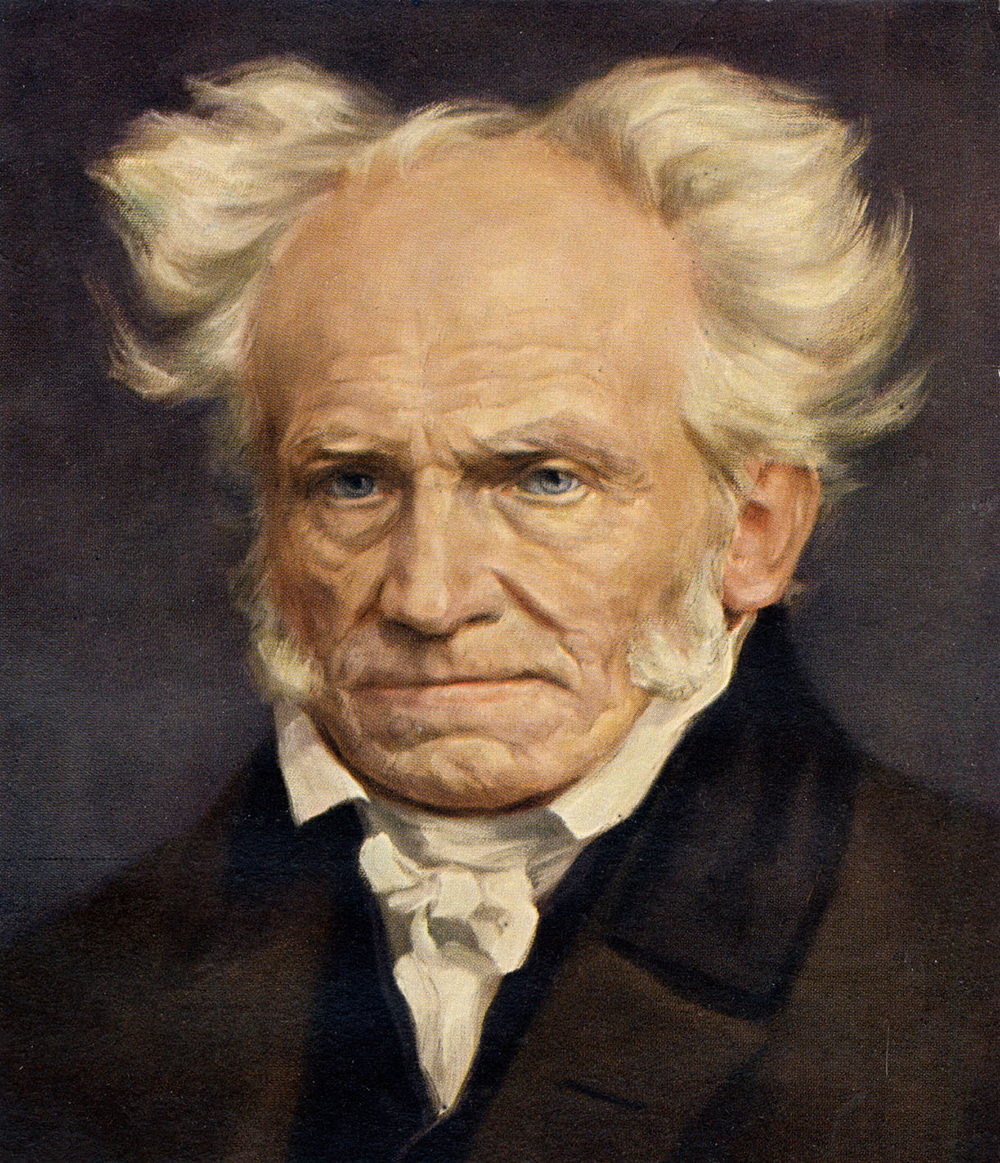

Tony Blair has been at the digital ID game a long time

Perhaps it is no surprise that Keir Starmer’s government appears to be warming to a rollout of digital ID cards. Tony Blair has been at the digital ID game a long time. He’s argued it’s necessary for public health, to save taxpayers’ money and to control migration. According to Blair, ‘digital ID is the disruption the UK desperately needs’.

On the face of it, all this presents a puzzle. Britain’s lack of appetite for compulsory ID is so marked that you could almost consider it a national characteristic, like a predilection for queuing or tea. Hence the pronouncement by Boris Johnson in 2004 that he would ‘take that (ID) card out of my wallet and physically eat it in the presence of whatever emanation of the state has demanded that I produce it’.

Boris is not alone in being so vehemently anti-ID cards. So why does the spectre of digital ID keep reappearing? Perhaps the answer lies with an informal Labour establishment working behind, or alongside, the government. Labour Together was set up in 2015 by a group of MPs – including Steve Reed, the now-Environment Minister – who wanted to get the party back into power. The BritCard report’s lead author Kirsty Innes’ previous job was at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. In 2021, she wrote a report making the case for vaccine passports.

It looks as if the reason digital ID won’t go away is that, far from there being a groundswell of public demand for it, this half-hidden group really, really wants it. That might explain another puzzling thing: the extraordinarily poor quality of the public discourse about the subject.

Take Labour Together’s opening gambit in the report’s foreword by MPs Jake Richards and Adam Jogee: ‘This is your country. You have a right to be here. This will make your life easier. It is at the heart of the social contract’.

Such disjointed statements belong more to a speech by a propagandist than a serious policy document. A vague appeal to nationalist sentiments is followed by the promise of ‘convenience’ which seems to accompany so much of the sales talk around the expansion of the digital state.

The claim that digital ID somehow fulfils the social contract – the democratic concept which makes political authority conditional on respect for fundamental rights – is baffling.

Baffling until you read further and discover the link is an attempt to convince the public that digital ID might be the solution to tackling illegal immigration. In a poll which forms the basis for the main argument, respondents were asked to what extent they would support digital ID if used by employers, landlords and public service providers to check a person’s legal status. Some 80 per cent replied they would support such checks. And so Labour Together concluded that digital ID would be ‘immensely popular’.

But when asked about the ‘most significant benefits’ of digital ID, only 29 per cent thought it might deter illegal immigrants from coming to the UK or accessing public services. Meanwhile, 40 per cent feared that digital ID could be misused by government; and 23 per cent thought it could increase the black economy. The disparity illustrates something well known in the polling world: question is all. Frame something a particular way and you’ll get one result; frame it another and you’ll get something quite different.

Polls have become tools of political persuasion. Too often, those commissioning them appear to have decided what outcome they want. As a result, they can be used to create the impression there’s public support for something. That feeds into a lazy ‘we might as well – everyone else is doing it’ kind of thinking, a line children often use on their parents.

Polly Toynbee, writing in the Guardian, uses it in her comment piece on the Labour Together proposal. We might as well agree to digital ID, she suggests, because privacy is already lost:

‘Some will protest at the apparent loss of a romantic freedom, the right to vanish and start life anew, the call of the open road. But that’s a fairytale, a fantasy of a bygone era. Everyone knows everything already’. Algorithms throw up personalised adverts, ergo, she concludes, ‘better to control everything from one government-run base’.

This kind of unthinking deflection makes civil liberty campaigners put their heads in their hands. Privacy became a basic right in modern democracies for a reason: why are policy people proposing to casually abandon a core principle? And why are they disregarding very real concerns about putting huge amounts of personal information into a leaky centralised system?

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, Andrew Orlowski points out that One Login, which links our personal identification documents to other government bodies and third parties, has a terrible track record on data security. ‘An insecure system has serious consequences,’ he says. ‘It not only puts individuals at risk of identity theft and impersonation, but also makes defrauding the government much easier…An ID system like One Login is where criminal gangs would go first, and BritCard will forcibly enrol you into it’.

Politicians and policy wonks throwing lines out until they finally get a bite from enough of the public won’t do. In a functioning democracy, public reasoning has to be of a certain standard if it is to lead to workable policies underpinned by genuine public consent. Shouting ‘yay! Disruption!’, as Blair appears to, won’t cut it – nor will Toynbee’s absurd claim that digital ID might help see off Nigel Farage. Radical departures from core values need proper consideration to ensure they serve the common good, not partisan interests.

The Home Affairs Committee has launched an inquiry into the potential benefits and risks of digital ID. Let’s hope that, as the parliamentary body charged with the scrutiny of domestic affairs, it will take a long hard look at both principles and consequences. The truth is that Brits don’t want, or need, ID cards.

Comments