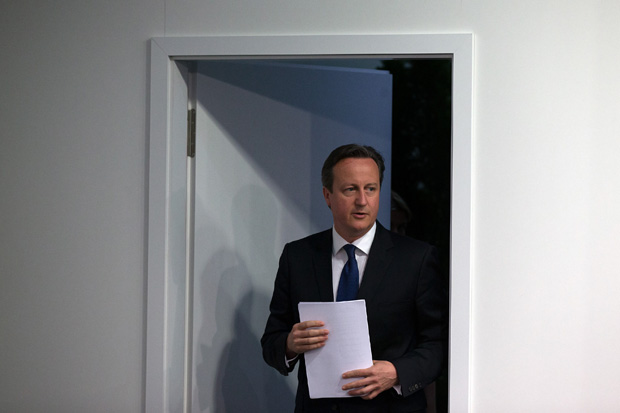

At 6.30 p.m. on 7 May, the Camerons invited guests at their home in Oxfordshire into the garden for a drink. Everyone stood on the patio, wrapped up in coats and shawls and drinking wine. They were understandably nervous. The Prime Minister had prepared a resignation statement and read it out to the assembled gathering.

The group that huddled together on the patio that day tells us a lot about the qualities which Cameron values in people. Most of them were close to him long before he entered No. 10. Ed Llewellyn, his chief of staff, worked with him at the Conservative Research Department more than 30 years ago. Kate Fall, Llewellyn’s deputy, was one of the first to sign up when Cameron went for the Tory leadership in 2005. Even the campaign photographer, Andy Parsons, did the same job back in 2010. Craig Oliver, the director of communications, is the only one to have been admitted to the inner circle since Cameron became Prime Minister.

One of the things Cameron says he likes about his team is that they are a calm bunch. But that evening there was plenty of emotion as he tested his leaving speech. It seemed all too possible that he would be delivering it for real in a few hours’ time.

At 9 p.m., Cameron had a conference call with various members of the cabinet in order to prepare them for the turbulent night ahead. Even if the Tories led on seats, he told them, Labour would try to use SNP support to force him out of No. 10 by the weekend.

An hour later, of course, the exit poll was released and the mood shifted dramatically. But Cameron had not just written his resignation speech that night; he had had a glimpse of what posterity might have to say about him. The experience has informed his every act since returning to Downing Street.

The Prime Minister has no interest in trying to rewrite history to suggest that the Tories always knew they would win. At a party for No. 10 staff last Thursday, he joked about how they had shared his confidence that he’d be back. One member of his inner circle remarks with satisfaction that the night gave a measure of both Cameron and Ed Miliband. The Prime Minister had not prepared a speech for outright victory; his opponent hadn’t prepared a speech for outright defeat. All of this helps explain why the government has sometimes seemed surprised by the prospect of having to implement its manifesto.

Few things annoy Cameron more than the suggestion that he is an ‘essay-crisis Prime Minister’ who prefers to ‘chillax’ until the last minute. He has been conspicuously busy since the election. While his family went on holiday to Ibiza, he toured European capitals to drum up support for his re-negotiation. He had to eat 12 courses in 24 hours, which will not have helped him to get ‘beach-body ready’ this summer.

No. 10’s focus is now on ‘delivery’: that is Westminster-speak for getting things done. In the coalition years, Downing Street had to act as a relationship guidance service; an inordinate amount of time was spent resolving disputes between Tory cabinet ministers and Nick Clegg. And Cameron was in any case keen to avoid the command-and-control structures of Blair’s presidential No. 10. All that has changed. The new Downing Street set-up, full of implementation committees and the like, would be instantly recognisable to anyone who had worked there under Blair.

Having won a majority, the Tories are determined to use it to secure another. One priority is to keep the seats they won from their former coalition partners. I gather that Tory HQ is already planning how to knock out Liberal Democrat councillors in these constituencies in the forthcoming local elections, denying them a base from which to recover.

The Tories also fought the election on a promise to reduce the number of MPs from 650 to 600. It had been assumed Cameron would quietly abandon this pledge rather than have Tory MPs fight one another for re-selection — even if it did redraw constituency boundaries in a way that favours their party. But I understand No. 10 is pressing ahead. They reckon that any MP likely to lose their seat can either be found a new one or sent to the Lords.

This will all be for naught if the Tories end up feuding over Europe so badly that the public just wants to kick them out in 2020. In private, Downing Street reckon that winning the referendum, by which they mean getting Britain to stay in on new terms, will be the easy bit. It’s the next bit that will be difficult: putting the Tory party back together.

George Osborne believes that the party will be fine as long as there is nothing that Eurosceptics can label a ‘great betrayal’. This is why it would be a huge mistake to rush the referendum. Imagine how the Tory party would react if the vote was held next year after a minimal renegotiation, only for Greece to leave the euro a few months later and trigger dramatic changes in how the EU functions. Cameron’s job now is to drive the best possible bargain from Europe. To do so, he needs to make it more explicit that he won’t campaign for an ‘yes’ vote unless he get what he demands.

Cameron can be forgiven for stumbling this week, as he tried to explain what would happen to ministers who disagreed with him on Europe. He didn’t expect to be running a majority government, one that is able to say what it likes.

He now faces the problems of success: how to manage his party when he doesn’t have the Lib Dems to blame; how to make most of a few months in which opposition is virtually nonexistent. He has pledged to stand down before the next election. When he leaves Downing Street, he will either be the man who ushered in a new era of Tory majority politics or the one who split the party over Europe. Whatever happens, he’ll have more to say in his resignation speech than he did a month ago.

Comments