Here we go again. According to today’s Daily Express, leaving the European Union is the only way to ‘save the NHS’. According to the Prime Minister, remaining a member of the european club is the only way to guarantee the United Kingdom’s security.

I suppose it is too much to hope that everyone, on both sides of this increasingly-wearisome argument, will pipe down and cease being so damn stupid? Of course it is. We will be stuck with more – much more – of this until such time as the bleedin’ poll is called and held. This may be the best reason for having the referendum as soon as possible.

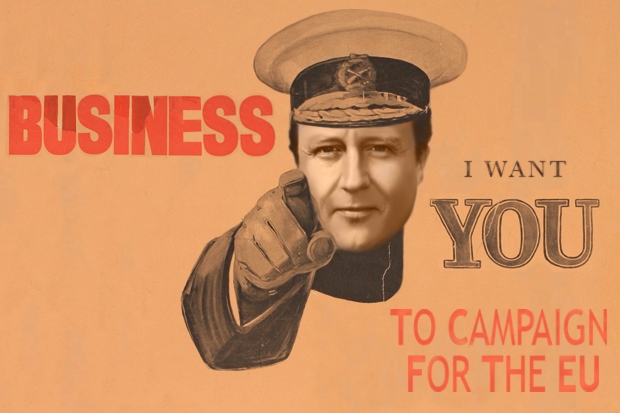

Now the boss is obviously right to observe – and even complain – that David Cameron and the other Inners are running a deplorably negative campaign that appears to be based on the premise that a hefty proportion of the populace are witless ninnies, easily scared into doing the ‘right’ thing. Immigration! Terrorism! Plus two other Horsemen to be named at a later date! (Once we’ve thought of them, that is.) This is neither especially attractive stuff, nor the kind of ennobling tactics liable to appeal to swanky metropolitan types and political ‘insiders’.

But it will probably work. The In campaign’s job is to hold onto as many of its voters as it can. It is not in the business of winning converts. For the simple reason that people who decided to be Out did so, in the main, some time ago. And once that rubicon is crossed, the die is cast.

Look at the polling numbers, helpfully supplied by YouGov:

As you can see, in general terms, a third of voters have for a long time been in favour of leaving. Now some of this support for Out might be soft and couched in woolly or abstract feelingsball terms but much of it is pretty solid and unlikely to be reached by the In campaign. It’s gone.

Add the kind of growth you should expect for Out over the course of the campaign (it being easier, in some ways, to increase your support from a low-level than when you start with a majority) and it becomes clear, I think, that 40 percent for Out is about the minimum you should expect the Outers to win. They, after all, should be the ones making the running for most of the campaign.

But getting to 40 percent is, all things considered, the easier part of the struggle. The last ten percent is a mountain of a different class and magnitude.

Not least because heroic wishful thinking and optimism can only take you so far. This is so even when the stakes, as in some referendums, are high but also when, as in this one, they are comparatively low. (They are higher than in the Alternative Vote referendum but closer to that plebiscite than to another, more recent, referendum about which there is no need to speak today.) In the end, promises of endless sunshine are no more useful, and possibly less persuasive, than promises of eternal rain. There are many reasons for this but one of them is that you already have all the people who will believe in the sunshine argument.

On the other hand, people who do not care very much about the argument – especially an argument in which they do not think they have much at stake – can be persuaded to stick with an imperfect status quo if, that is, the risks of change seem greater than any plausible benefit that might arise from that change. The In campaign, then, needs to increase the cost of Brexit. This will, for sure, require some sleight-of-hand and exaggeration. But this, it should be noted, is no more daft than the with-one-bound-we-are-free stuff peddled by the Outers.

After all, when ordinary people hear the Brexiters shouting about becoming, once again, a ‘free country’ they wonder what on earth these people are talking about. To put it this way, comparatively speaking, the EU’s bondage would be considered tame by any number of former Tory MPs (and, perhaps, some current ones). ‘Give me liberty or give me death’ is all very well but more people just want to be able to get to Magaluf.

And, in any case, what is the inspirational, poetry-stuffed, pro-EU campaign? Even if it existed, where would you find it? And even if you could find it, would the people recognise it? I doubt that very much.

No, in the end the In campaign will be dull and tedious and negative and all the rest of it. It will also, probably, win. But if it does it will not be because it ran a better campaign than the Outers or even because it has a greater purchase on the people’s imagination or sense of self-interest. No, it will be won by something else.

That something is the fact that on one side you have David Cameron while on the other you have luminaries such as Nigel Farage, Iain Duncan Smith, Chris Grayling and even, perhaps, Jeremy Corbyn. A contest, then, between the electable and the unelectable. The people in the Out campaign are the In campaign’s greatest weapon. This is harsh on some of them but not harsh enough on many others.

Comments