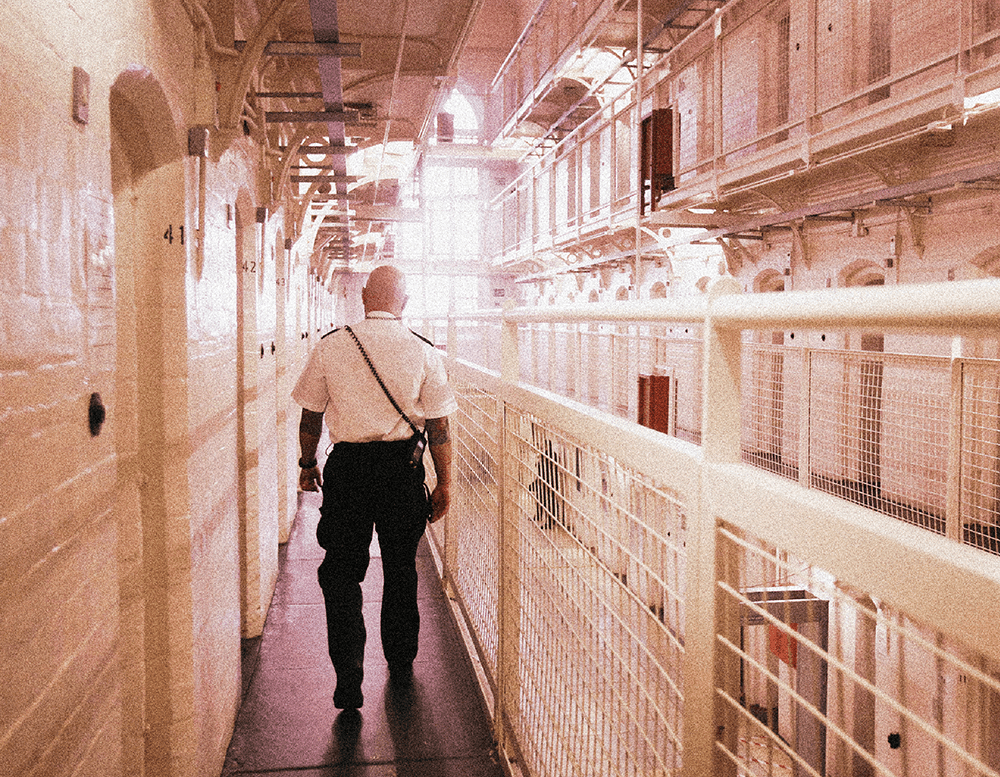

While we were inspecting HMP Elmley on the Isle of Sheppey, a commotion broke out on one of the wings. ‘What’s up?’ one of my team asked the nearest prison officer. ‘Bloke who’s getting out tomorrow has just been told he’s being shipped to Rochester jail.’ The man was manhandled towards a prison van. ‘If I was him, I’d kick off too,’ the officer added quietly.

Reducing the prison population will do nothing to stem the flow of drugs pouring into every jail in the country

That week things were so desperate in the south of England that the prisoner was being forced to spend one night in a jail 20 miles away so that new arrivals could be squeezed in that afternoon. Jails were 99 per cent full and governors were under instructions to make every possible place available.

This is the context in which the former justice secretary David Gauke publishes his report on sentencing this week. Ministers hope he will find a way to reduce the prison population from current historic highs. That would give the most overcrowded jails, such as Elmley, Leeds and Bristol, breathing space to deal with the other problems they face.

Recently published statistics showed a 13 per cent increase in assaults on staff and seven murders in the past year. Self-harm among prisoners has reached a new high – particularly in women’s prisons. Ever-increasing levels of violence and recent high-profile assaults by notable prisoners at Frankland and Belmarsh have led ministers to announce that some prison officers will soon be issued with Tasers.

In the three public-sector young offender institutions, consistently the most violent prisons in the country, the use of pepper spray on children has been authorised. The government has also commissioned a review into the use of body armour following pressure from the Prison Officers’ Association.

At HM Inspectorate of Prisons, we continue to report that many prisoners are locked in their cells for up to 22 hours a day. Some jails, such as Wandsworth, simply do not have enough space to provide everyone with work or education, while in the best-equipped and most spacious jails, we find half-empty workshops and classrooms. Many prisoners are on wing-cleaning duties, which involve pushing a mop round for an hour or so and then spending the rest of the day loafing about, vaping and chatting to their fellow ‘workers’ – hardly adequate preparation for the world of employment. Half of all prisoners are functionally illiterate, yet few prisons are teaching inmates to read and write.

Reducing the population will do nothing to stem the flow of drugs pouring into every jail in the country. Drones can drop off packages direct to individual cells, from which the contents can be dispersed round the prison in hours. The heaviest payload I have come across was 11kg; it contained mobile phones and enough drugs to disrupt the prison for a whole weekend. We now regularly smell cannabis on the wings and prisoners can often choose from a menu of drugs.

When we inspected HMP Hindley outside Wigan, prisoners from criminal gangs operating in Manchester and Liverpool had made it the worst prison in the country for drugs, with random tests showing that more than half the population was under the influence. With little to occupy their time, it is not surprising that we meet many prisoners who have developed a drug problem since they have been inside. The idea that any rehabilitation is going on in such an environment is fanciful.

We found significant drone incursions at Manchester and Long Lartin, prisons holding some of the most dangerous men in the country, including terrorists and organised crime bosses. These men are often serving very long stretches and have little to lose. If weapons or explosives get into one of these jails, the consequences could be terrifying.

Prison governors, a remarkably stoical and dedicated class of public servant, are desperately trying to hold the line. The best are able to run successful jails despite the problems but they have less autonomy than I had in my former life as a head teacher.

Even the most experienced have their freedom to operate stifled by a bureaucracy that encourages plodding managerialism over transformative leadership. Governors, for example, have no involvement in the recruitment of new officers. There are no face-to-face interviews, so it is no surprise that around a third of recruits have left by the end of their first year. In some jails we come across officers with only eight weeks of training managing prisoners who have been inside for longer than their guards have been alive.

There are some impressive prisons that manage to buck the trend. Oakwood, outside Wolverhampton, is the largest prison in England and Wales, holding more than 2,000 men. Contracted to G4S, it is the best jail I have inspected, with high standards of behaviour and well-motivated prisoners who are helped by capable staff to transform their lives. At around £18,000 per prisoner per year, Oakwood also happens to be the cheapest prison to run in England. The open prison at Hatfield, outside Doncaster, also has an excellent record in getting prisoners into work on release – a critical factor in the prevention of future offending.

Last week’s announcement by the Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood means most prisoners will now be recalled to prison for only 28 days if they breach their licence conditions. This should stop jails from becoming full again later this year. It will also give time for the more radical reforms in the Gauke review to be enacted. The changes will, however, put more strain on already overstretched probation services, where inexperienced staff are managing large caseloads that concern some very risky men.

Even if ministers solve the prison population crisis, they will still be left with a proven reoffending rate of 27.5 per cent. The system is palpably failing to rehabilitate those in its care. It costs, on average, almost £57,000 to keep someone in jail for a year. That is a lot of money to spend simply to keep criminals locked in their cells, stoned on drugs and watching daytime television.

Comments