The Foreign Secretary David Lammy will touch down in Beijing next week to pay his respects. Next year, Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor, is expected to do the same.

We haven’t seen this level of deference to the Chinese Communist party since 2019. Back then, Philip Hammond heaped praise on his hosts. He endorsed their Belt and Road initiative – of Chinese-funded infrastructure spanning the globe – and promised British co-operation ‘as we harness the “Golden Era” of UK-China relations’.

The calls from Tory China hawks to label Xi’s empire ‘a systemic threat’ hold little sway with the new regime

That was the high-water mark of Anglo-Chinese collaboration. George Osborne and David Cameron had courted the Chinese hard. Boris Johnson, too, was initially tempted to follow a pro-Sino approach – backing Huawei for 5G access. But, under pressure from the US, he stepped back, concluding that China posed a substantial threat to the liberal global order. The Belt and Road initiative soon began to be seen as a Beijing power grab – a way to spread influence with strings attached. Then came the Hong Kong crackdown, more accusations of espionage, cyber attacks, human rights abuses – followed, of course, by the Covid pandemic. The UK-China relationship turned from warm to wary at best. ‘They tend to start off thinking there is a third way,’ says one Whitehall figure. ‘Then they realise you can’t negotiate with China.’

But Labour is looking afresh at what Beijing has to offer. For a government with growth as its central goal, the Chinese market is alluring. When money is tight, the world’s second-largest economy looks like a more appealing place to turn. China has plenty to invest in return.

Lammy’s trip should provide an indication of how far Labour is prepared to go to embrace Beijing. It has already been conducting a China audit, aimed at setting a general direction across government. The first fruits will be published shortly. Those privy to the work in progress suggest the idea is a course correction from the past 14 years of Tory rule. The government will set out where Britain differs from China but also, crucially, those areas where collaboration should be welcomed.

There are various signs to suggest the way the wind is blowing. In its first few months in power, Labour paused the Free Speech Act, which contained protections against Chinese interference in universities. The Tories suspended significant economic co-operation with China after Beijing imposed its repressive national security law in Hong Kong in 2020. Lord Mandelson criticised that decision last month. Now relations can resume. The decision to cede sovereignty over the Chagos Islands and hand them over to China’s ally Mauritius is another indicator of broader détente (though officials insist the US government backed the move).

In 10 Downing Street, much of the institutional memory on China has gone – John Bew, the foreign affairs adviser to the last three prime ministers, is out. Keir Starmer’s new foreign affairs lead is the former civil servant Laura Hickey – very respected but someone who specialises in the Middle East. This week, Starmer appointed a new head of strategic communications, James Lyons, straight from TikTok, the Chinese-owned social media firm.

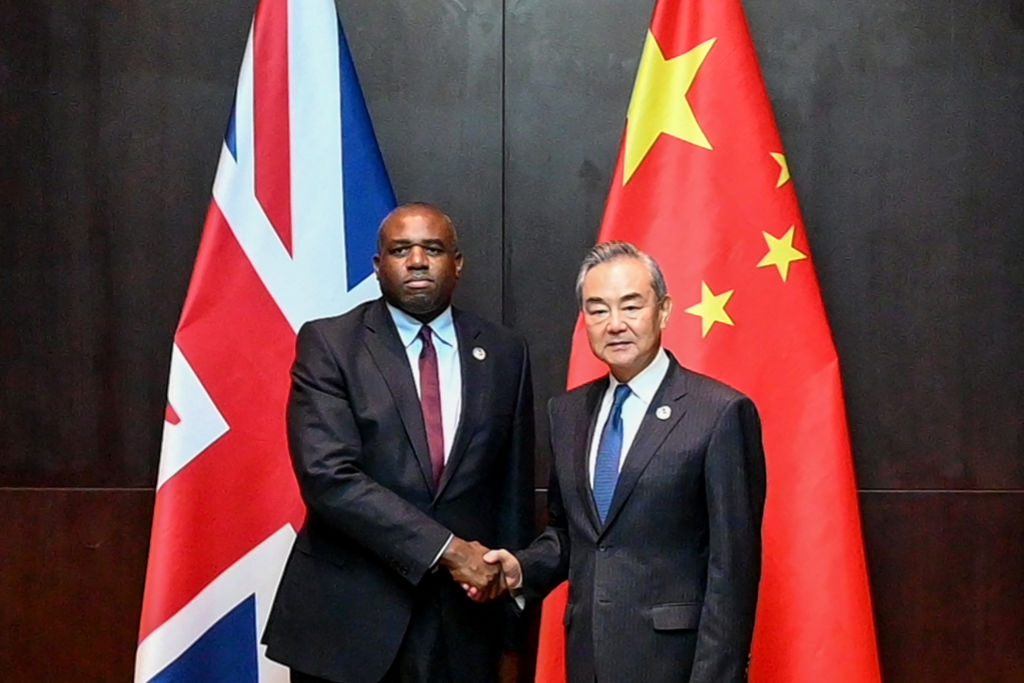

Foreign Office sources play down the intensity of any rapprochement. Lammy’s supporters point out that even the US, where a bipartisan anti-Beijing consensus holds, has engaged directly with Chinese leaders. When he met his Chinese counterpart in July, I’m told, Lammy privately raised concerns about human rights, Hong Kong, sanctioned British parliamentarians and the imprisoned businessman and dissident Jimmy Lai – as well as Beijing’s dealings with Russia against Ukraine.

These concerns are real. Yet so is the glimpse of an opportunity to open new lines of communication and channels of investment. Dialogue is viewed as key. The insulting rhetoric and the tabloid-friendly calls from Tory China hawks to label Xi’s empire ‘a systemic threat’ hold little sway with the new regime. ‘It’s a waste of time and energy,’ says one party figure.

Add to that the change in the backbench pressures. The last four Conservative leaders fronted a mutinous party that would not allow too close a relationship with China. If Boris Johnson hadn’t U-turned on Huawei, his MPs may well have made the decision for him. Several Tory politicians have been sanctioned by China (a badge of pride in the leadership contest); not a single Labour MP has. It is true that John McDonnell, the former shadow chancellor, has spearheaded efforts to stand up for the Uigher Muslims – but he is currently without the whip.

If Ed Miliband is to have any chance of delivering clean electricity by 2030, China will be key

This all means that Starmer and his ministers have some room to manoeuvre. There are two main areas where China could be helpful. On the economy, Reeves has a dilemma concerning growth. It’s the main mission of the government, but she is facing obstacles as consumer and business confidence fall amid dire warnings about the state of public finances. Establishing closer relations with the EU is both time-consuming and politically unpalatable (rejoining the customs union is seen as a no-go for the first term). So it’s only logical that Reeves will look to other markets for growth.

The importance of this mission was hinted at this week when the head of MI5, Ken McCallum, gave a rare public address. After warning repeatedly about the threat from Iran and Russia, he suggested that China was different, as the ‘UK-China economic relationship supports UK growth – which underpins our security’. He went on to say that it ‘rightly’ falls to ministers ‘to make the big strategic judgments on our relationship with China’.

One key test is Shein, the £50 billion fast-fashion chain, accused of human rights abuses and environmentally unethical practices. The China-founded company had planned to list in New York, but the plan fell apart following opposition from US politicians. So far, there are no such problems here. Reeves sounds more open – previously noting: ‘I want Britain to be a place of choice to IPO and grow your business.’

The expectation is that Shein will be given the go-ahead. With current concerns in the City that the London Stock Exchange is running aground, Reeves can hardly afford to sniff at it. Next week, she will host the government’s investment summit – where HSBC will be among the companies present. It was meant to be a big moment for her plans for growth. However, worries about the Budget mean that the event is proving rather tricky.

‘It doesn’t make sense to do it before the Budget,’ says one attendee. Business will want answers to questions on tax that the government will not be able to give. The mood among attendees has not been helped by the fact that an email was sent to them with their contact details in full view. ‘They didn’t BCC anyone, it’s amateur hour,’ says a recipient.

If the summit doesn’t deliver all that is hoped, more openings to China may prove increasingly attractive. There will be shoals to navigate in any revival of trade with China. Labour will face crosswinds – not least from the United States. As Johnson discovered, if the UK goes too far, its counterparts across the pond will make their voices heard. Should Trump win next month, there will be more pressure on Britain. In 2020, amid the Huawei controversy, the US secretary of state Mike Pompeo flew across the Atlantic to urge the UK to change course.

Another issue is steel. De-industrialisation is a live concern in No. 10. Thousands of jobs have been lost at the Port Talbot steelworks in south Wales. This week the Tees Valley mayor Ben Houchen went public with his concerns that the Scunthorpe steelworks are next in line. If the UK stops producing steel, it will have to look abroad for imports. Houchen is concerned that China will be the ultimate beneficiary.

Labour MPs in seats where Reform came second are already panicked. ‘Reform’s threat over Labour is completely bound up in the question of what is a sustainable growth model for places like Port Talbot,’ says an MP. Some in the party hope the promotion of Morgan McSweeney, a blue Labour strategist, to Downing Street chief of staff this week could help.

But McSweeney will know that it’s not just on growth that Labour could seek Beijing’s embrace – it’s also on energy. Ed Miliband is the most energetic of Starmer’s cabinet, which is natural given that he has the most ambitious of all Labour’s pledges to deliver: clean electricity by 2030. Many of Miliband’s colleagues see that target as pie in the sky – but if he is to have any chance of reaching it, China will be key. The country produces 86 per cent of the world’s solar panels – some of which have been linked to forced labour. When it comes to batteries, the rare-earth minerals that are needed come largely from African countries which Beijing has a grip on through its Belt and Road initiative. ‘If Ed stays in post, they can’t meet the targets unless you are relying on China,’ argues a former minister.

China’s dominance of the electric-vehicle market is already well established. Where the US and EU have slapped heavy tariffs on China’s cheap EVs, the UK is so far resisting that move. Officially, no final decision has been made – but Reeves’s instinct is not to follow suit. The question is whether America will start to exert pressure on the Foreign Office. China could ease the transition and reduce the cost of the switch to electric vehicles for the consumer. If it does so, though, the British government could be handing China control over one of the industries of the future. Is that wise?

For Reeves and Miliband and their government-defining missions, China may soon seem to be the indispensable partner. For want of a better alternative, Labour could find itself re-entering the dragon’s den.

Watch more on SpectatorTV:

Comments