Yesterday, the Irish government announced that there will be a General Election on Saturday, February 8. Curiously, the path to it was cleared by Boris Johnson’s decisive electoral win last month. Up to now, there has been no desire on the part of either the government or the main opposition parties to hold an election because of the uncertainty surrounding Brexit. Partisan politics were largely set aside, all the parties donned the ‘green jersey’ and teamed up with Brussels to try and ensure either the softest possible Brexit, or no Brexit at all.

The united front disguised the fact that, Brexit-aside, the Leo Varadkar-led Government has been a lame duck for months. It has been dogged by a housing and healthcare crisis, and under normal circumstances these might have triggered an election. But thanks to Brexit and the resultant turmoil, normal politics in Ireland has been in a state of indefinite suspended animation.

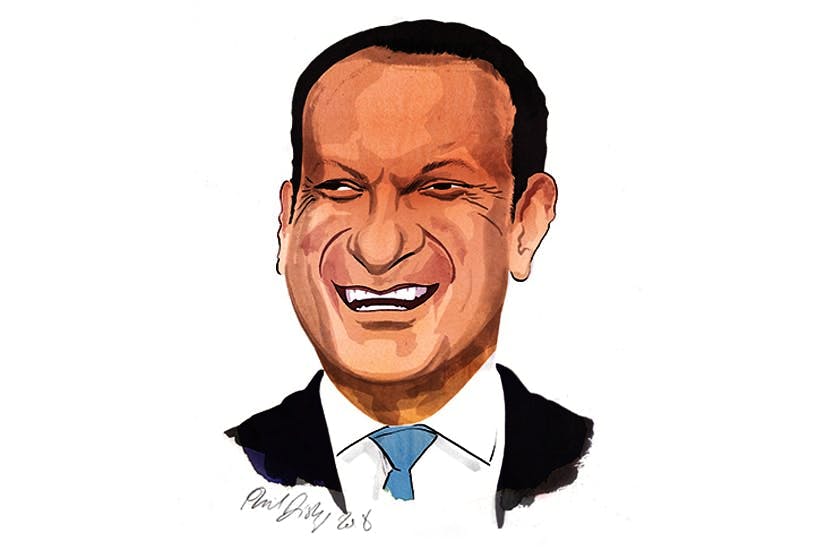

But now that a deal has been struck and an election announced, things are not looking particularly good for Leo Varadkar. It must be remembered that Varadkar has never actually faced the Irish people as the leader of Fine Gael. He became Taoiseach in 2017, following the resignation of his predecessor, Enda Kenny. In the subsequent leadership race, he won because of his strong support base within the Fine Gael parliamentary party, but two-thirds of the Fine Gael rank and file voted for his rival, Simon Coveney, who is now Tanaiste and Minister for Foreign Affairs. This alone makes Varadkar’s position look fragile. If he couldn’t get ordinary Fine Gael members to vote for him in 2017, how will he fare in the upcoming general election?

It’s unlikely that Varadkar will benefit much, if at all, from his strong stance against Britain during the Brexit negotiations. His hardline position on Brexit surprised many British politicians, as Fine Gael has traditionally been the least anti-British Irish party, relatively speaking. Under Enda Kenny, Fine Gael behaved as expected and the party adopted a pragmatic attitude towards Brexit and the issue of the border with Northern Ireland. Irish civil servants sought to work out post-Brexit arrangements with their British counterparts that would minimise as much as possible the need for checkpoints etc. at the border. But when Leo Varadkar took over, this came to a shuddering halt. Dublin and Brussels seemed to decide that the border and the Peace Process might become the issues on which Brexit itself was dashed to pieces. The weakness of Theresa May invited an aggressive, hardline position.

Varadkar and Simon Coveney seemed very keen to wrap themselves in the green flag. They knew it would unite voters and ensure that Fianna Fail couldn’t outflank them in a bid for patriotic Irish voters. And thanks to the deal Leo Varadkar and Boris Johnson struck in Liverpool last year, the way was cleared for a new withdrawal agreement between Britain and the EU which ensured there will not be a hard border on the island of Ireland. But will that do Varadkar much good in the election campaign? Probably not. Precisely because every party wore the ‘green jersey’, the credit for avoiding a hard border in Ireland has been shared.

Varadkar has some factors in his favour. The Irish economy is doing well, and that should benefit the incumbent Fine Gael. On the other hand, the fact that the government has plenty of money at its disposal only adds to the public annoyance that it still hasn’t solved the housing and healthcare crises. Fine Gael has also been in power for almost a decade now, and voters generally tire of any given governing party if it has been at the helm for a long time.

Other episodes have also called into question Fine Gael’s republican credentials. For a reason few in Ireland can fathom, the government thought it would be a sensible idea to commemorate the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as part of a series of other events being held in the run-up to the centenary of Irish Independence. The RIC was one of the principal enforcers of British rule in Ireland – why would any self-respecting nationalist party wish to remember them? Fianna Fail and Sinn Fein were quick to attack the Government over the matter and the commemoration has now been postponed. On its own, this episode seems relatively minor, but it has damaged the Government’s reputation for competence.

What will happen in the upcoming election? Well, no party wins an overall majority in Ireland anymore, and Fianna Fail is the only one that ever did. We always have coalition Governments now. Pundits are currently predicting that Fianna Fail will emerge from the election with more seats than Fine Gael. But no matter what happens, the parties will go into a big huddle following the election and after protracted talks will emerge in some combination to form the next Government.

One fairly big possibility is a Fianna Fail/Green/Labour coalition backed by a number of independent TDs. Another outside one (whisper it) is a Fine Gael/Sinn Fein coalition plus sundry independents.

Leo obviously will take as much credit as he can for avoiding a hard border on the island, but it is unlikely to get him very far. Old-fashioned issues will predominate instead in this election, namely the economy and the state of public services. Newer environmental concerns will also feature. For the purposes of the election, the green nationalist jersey is already last season’s look.

David Quinn is a columnist with The Sunday Times (Ireland edition).

Comments