It’s climate change again, innit. It didn’t take long for Sunday’s flooding in London to be put together with Canada’s recent heatwave and the floods in Germany and China to be used as ‘evidence’ of ever-accelerating climate change – giving us even less time to save the world than previously thought. ‘More rain as Londoners call out climate change,’ screamed a headline on City A.M., alongside pictures of water pouring through Stratford DLR station and cars stuck on the North Circular. Sunday’s flash floods have also brought an old favourite out of the closet: a map purporting to show large parts of London which will be underwater by 2030 – and which actually shows areas which would be threatened, even now, by extreme tidal flooding if London had no flood defences (which of course it does have).

But is it really climate change wot flooded your local bus stop? One of the latest wheezes of climate alarmists is to argue that warmer air contains more moisture, and to use that to try to link any flood event to global warming. It is true that warmer air has the capacity to absorb more water vapour (which doesn’t necessarily mean it does contain more moisture at any particular place and time), but then warmer air also means more evaporation, with the result that when it does rain, that rain is less likely to land on saturated ground – so it doesn’t follow that warmer air necessarily means more floods.

But more to the point, is there any evidence that Britain is actually experiencing heavier rainfall? Sunday’s rain certainly didn’t break any records. The most intense rain measured that day (not in London but in Bethersden in Kent) was 48.5 mm in an hour. The record for rainfall in an hour is almost twice this figure – 92 mm measured at Maidenhead as long ago as 12 July 1901. As for London, the wettest place measured was St James’ Park where 41 mm was measured over 24 hours: heavy, but far from unusual in terms of what might be expected at some point in a typical year. There may have been wetter places than this – we don’t know because heavy rainfall tends to be very localised and London is not carpeted with rain gauges. But it is clear that while very heavy, Sunday’s storm was far from being a biblical-scale event which could only have occurred as a result of climate change.

More to the point, is there any evidence that Britain is actually experiencing heavier rainfall?

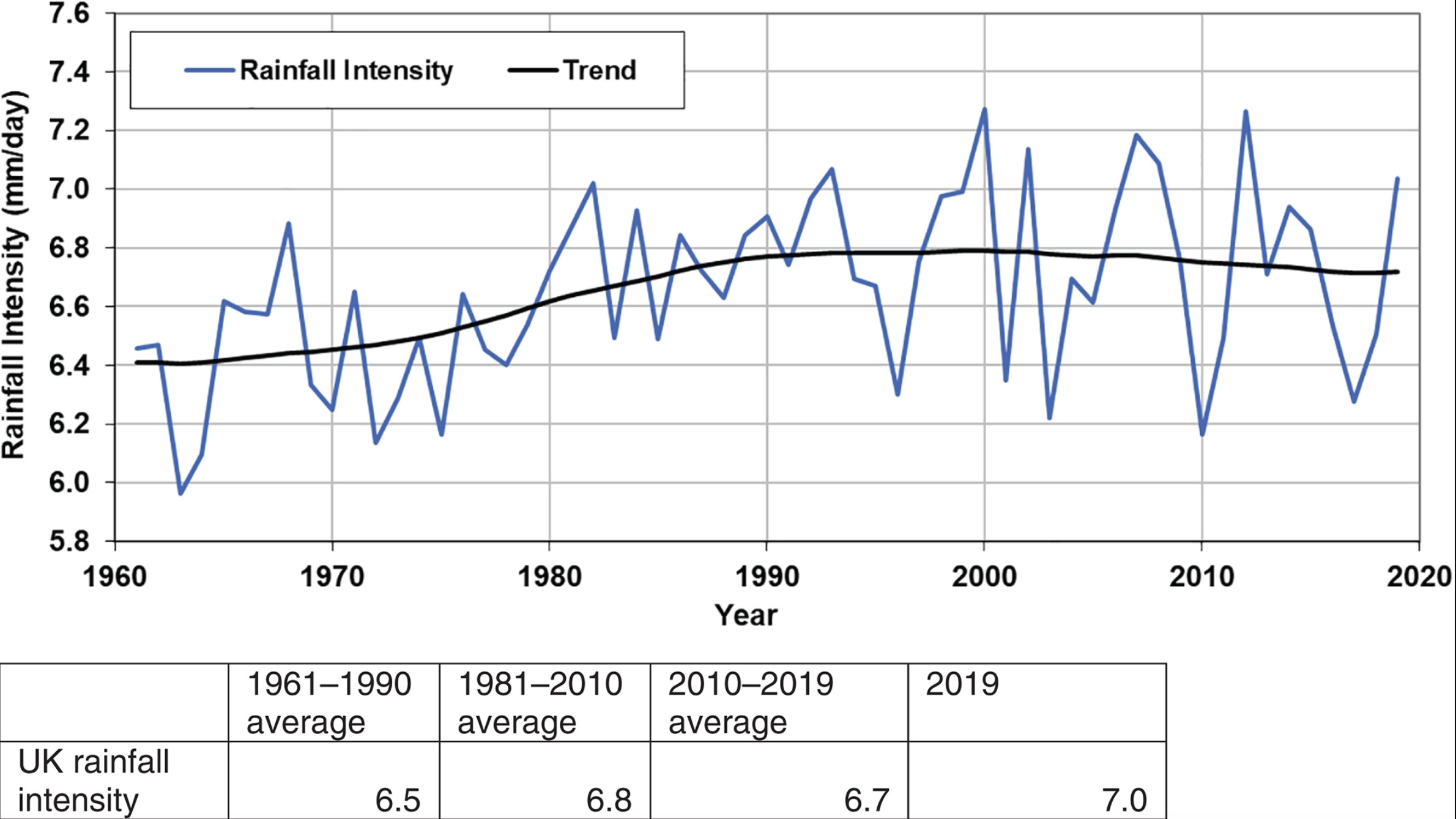

The Met Office uses several metrics for determining changes in damaging rainfall over time. The first, called ‘rainfall intensity’, measures mean rainfall on days which experience more than 1 mm of rain.

Records show that this increased from 6.4 mm in 1960 to 6.8 mm in the late 1990s but has since trended slightly downwards.

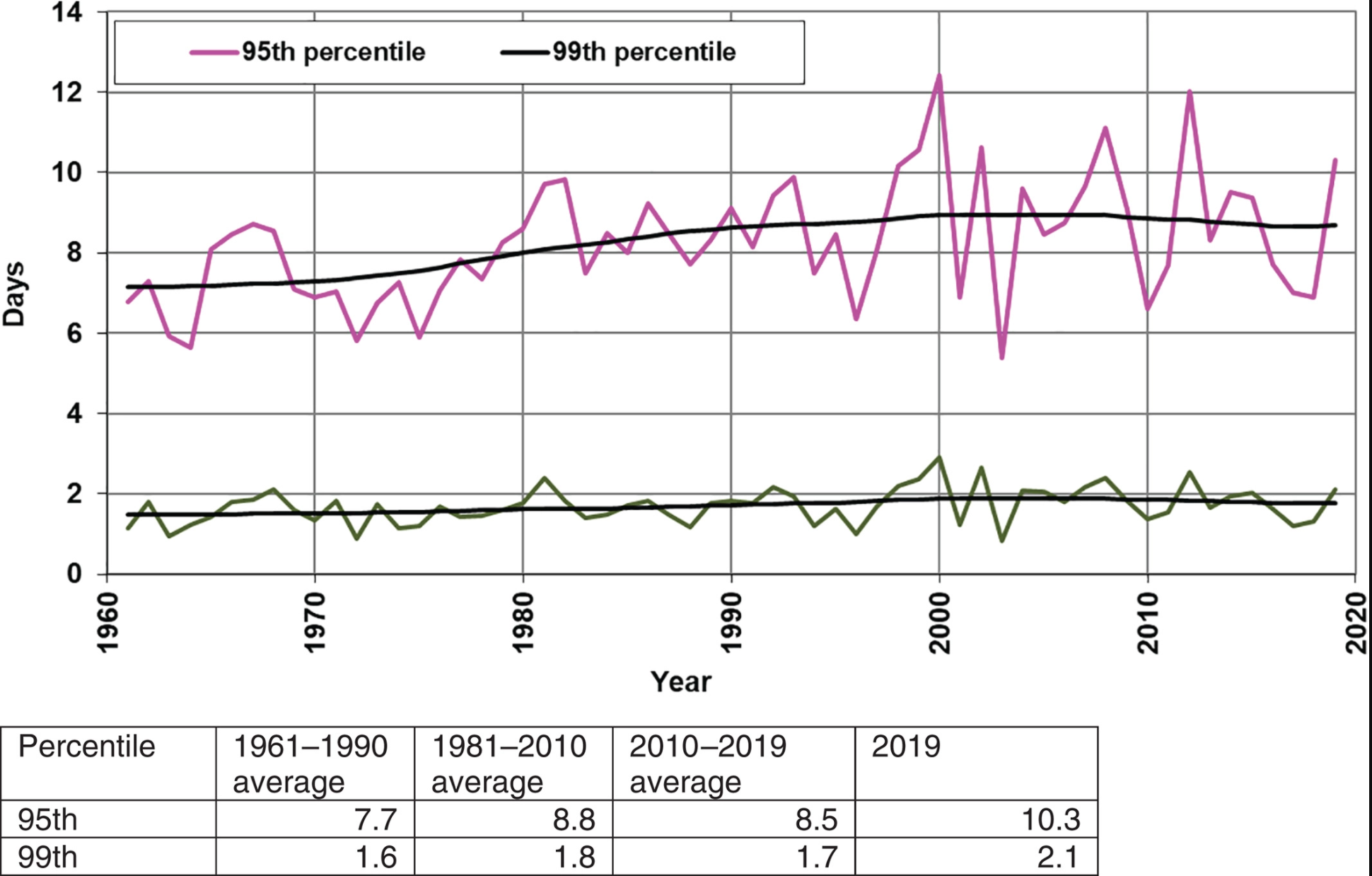

The second, called ‘Heavy Rainfall’, looks at the number of days where the quantity of rain exceeds the long-term 95th and 99th percentiles for daily rainfall in that location. The graphs for this metric show a similar story: a rising trend from 1960 to the early 2000s, followed by a levelling-off and slight fall.

Finally, the Met Office looks at the number of occasions when a weather station anywhere in Britain measures more than 50 mm of rain, adjusted for changes in the number of rain gauges, which have fallen from 5,000 to 3,000 over the past 40 years. This measure shows a steeper upwards trend from 1960 to 2010, followed by a levelling-off. However, the Met Office warns that this metric could be affected by a greater concentration of the remaining rain gauge network in upland areas.

Put it all together and – in contrast to rising temperatures – it is hard to discern any upwards trend in heavy rainfall over the past two decades. If anything, the frequency of heavy rainfall in Britain has decreased slightly. The published data doesn’t discern between summer and winter rainfall events, so it is not possible to say from this whether or not the country is seeing more or less intense summer thunderstorms.

What has changed over the past two decades, however, is an intensification of development in London. Large blocks of apartments have replaced some areas of open space, while Londoners have paved-over their gardens to provide car parking and because they no longer want to spend time mowing the lawn. I can’t vouch for this figure, but according to Mary Dhonau, former head of the National Flood Forum, London has lost 22 Hyde Parks-worth of absorbent gardens in recent years – which really matters in a thunderstorm when a lot of extra water is sloshing along streets and into drains which cannot cope. Of course, it suits many people in local government to blame floods on climate change rather than failures in the planning system which have allowed the absorbent land to be lost.

Comments