Shortly after he was elected as Britain’s youngest council leader last month, 19-year-old George Finch of Reform UK had a conversation with Monica Fogarty, the chief executive of Warwickshire county council, about which of them was really running the show. In Finch’s telling, this was a watershed moment: he offered a ‘professional working relationship’ but the relationship quickly soured.

‘I know you’re trying to get rid of me,’ Fogarty said, according to Finch. ‘Well, you can’t get rid of me. The way it works around here is: your councillors play ball.’ Finch allegedly replied: ‘Are you joking? You have to work with us. It’s not the other way around. We’ve been put here by the electorate. You haven’t.’ He says now: ‘The old Tory leader just gave her loads of delegated powers.’

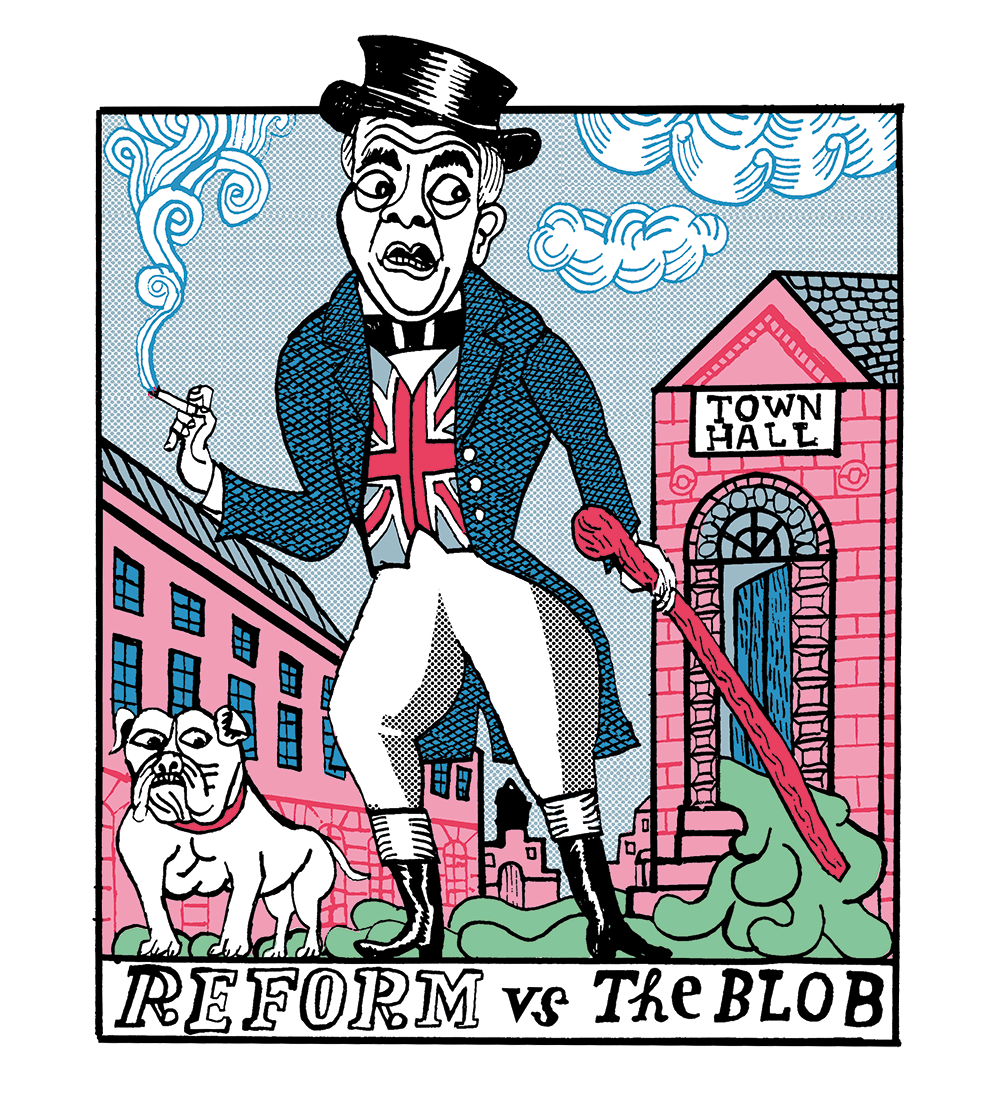

Reform has just marked 100 days running 12 town halls across the country, a period which has seen clashes between elected councillors and the permanent bureaucracy. These have been most acute in Warwickshire, ground zero in Reform’s fight to show it can get things done in the face of resistance from ‘the blob’ of permanent officials.

In Warwickshire, Finch and Fogarty first fell out when Finch demanded the removal of the Pride flag from council HQ. Fogarty refused, though the flag came down at the end of Pride month. When told she did not have the necessary planning permission to fly the flag, Fogarty said there was no formal policy for doing so. Finch is pushing for a ban, which requires a vote in full council.

The confrontation turned ugly after Finch says council legal advisers told him he wouldn’t have a leg to stand on if Reform opposed plans to remodel a junction, sending HGVs past a school to an industrial zone. ‘You can’t stop it,’ he was told. ‘You’ll go into judicial review.’ When the issue came up in council and an amendment was tabled to delay the plans, only at that point did the legal adviser reverse the advice and tell Finch he could defer a decision. His councillors told him he had been ‘stitched up’ by officials who had wanted to push the plan through. Reform backed the delay.

In Reform-run areas, there have been clashes between elected councillors and the permanent bureaucracy

Farage’s team point to Fogarty’s background as a race relations officer to say she was ideologically opposed to a crackdown on diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies. Finch says: ‘When it came to policy on DEI and net zero, it was literally like Yes Minister. Officials said: “Are you sure this is what you want to do? Voters might not like it.” But this is why we were elected.’ When Finch asked to look at Fogarty’s employment contract, he was at first told she didn’t have one. After three weeks, a document appeared with details redacted. Warwickshire county council declined to provide a response prior to publication to any of Finch’s claims.

Warwickshire is not the only battlefield. In Kent, where Reform is imitating Donald Trump’s Doge unit to slash waste, officials resisted moves to scrap a net-zero renewables programme that involved the purchase of a fleet of electric vehicles and was to cost nearly £40 million. Luke Campbell, the Olympic gold-medallist boxer elected mayor of Hull and East Yorkshire, told the Telegraph that officials were blocking his agenda. They say his ‘one-man band’ approach created a ‘toxic working environment’.

These clashes are a sign of what a Reform government might be up against if they win national power in 2029. Official resistance takes several forms: an ideological opposition by left-wing local officials to the policies of the populist right; a belief in experience over politicians who have not run a bath, let alone a £1 billion budget; a preference for process over political pronouncements; and a power struggle between those who have a public mandate and those who think they know best.

Simon Case, who worked for David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson in No. 10 and who wrestled with Dominic Cummings’s efforts to reform/blow up Whitehall, admits there can be ideological differences: ‘You have to spend a lot of time as cabinet secretary, reminding the whole system of what the civil service code says, which is that you’re there to support the government of the day, no matter how uncomfortable that is. Ultimately, if you don’t want to work for them, resign.’ He commends Oliver Robbins, the permanent secretary at the Foreign Office, who recently wrote to his staff telling them to resign if they didn’t like Labour’s policy on Gaza.

‘Politicians across the spectrum are united in their frustration that the system isn’t delivering’

Case has publicly recommended that the civil service admit Reform to contact talks with mandarins 12 months before the 2029 general election, if there is any prospect of them even sharing power. He says there is an onus on officials to anticipate ‘cultural changes’, as well as policy changes, to ‘learn the language’ of the ‘new boss class’.

When he presided over the transition from Tories to Labour, Case told civil servants: ‘Here’s a bunch of people who aren’t going to talk about “levelling up” any more. They care about exactly that same thing, but don’t call it “levelling up”. Read the speeches and read the manifesto so you understand their way of thinking.’

But he also urges Farage not to assume that he can simply transpose the lessons of Warwickshire on to Whitehall. ‘Politicians across the political spectrum are united in their frustration that the British system isn’t delivering,’ Case says. ‘The really interesting question for Reform is will they do the homework required to understand immediately the changes they need to make in how government works? Nigel Farage probably never spends time at the Institute for Government [thinktank] – but read what the IfG says about what is wrong with government, what is wrong with the bureaucracy and the laws that have put unaccountable officials in charge of things instead of politicians.’

Case says ‘most of the time’ clashes between officials and ministers come about because civil servants say: ‘Here are all the reasons why you can’t do what you want to do because you don’t actually have the power to do it.’ The main target for Reform is the European Convention on Human Rights, which lets judges defy ministers and voters on migration. But huge power also resides with quangocrats in arms-length organisations. Morgan McSweeney, Starmer’s chief of staff, complains that 60 per cent of government press officers are working against his own spin-doctors for taxpayer-funded organisations with agendas of their own.

Case can see a scenario in which a prepared Reform government produces a great repeal bill with the Brexit slogan ‘Take back control’. He explains: ‘If they did their homework, you could remove all of those obstacles at a stroke. It’s not just the top things, like scrapping the Office for Budget Responsibility, but here are all the people who can block planning applications for motorways or power stations. Here are all the statutory consultees every time you launch a new business support programme.’

Reform’s voters tend to think the system has failed and want to destroy it rather than make it function better. But Labour voters also thought the system had failed and they are now being let down by Starmer’s inability to deliver the change he promised. McSweeney spent the pre-election period working on how to win rather than how to govern, wrongly assuming Sue Gray was taking care of that. Since he replaced her in October he has, an ally says, become ‘infected with governmentitis’ – a near manic obsession with how the system fails.

Farage’s attention is now on how to secure national power for the first time, but if the opportunity is presented to him, it will be because everything else has failed and the whole country – as well as his voters – will need him to make a success of it. As America’s founding father Benjamin Franklin put it: ‘Fail to prepare and you prepare to fail.’ If Farage does not develop a plan for governing as well as winning, it won’t just be the blob that is to blame.

Join Michael Gove, Tim Shipman and Madeline Grant in Manchester on Monday 6 October for Coffee House Shots Live: Can the Tories turn it around? Book your tickets here.

Comments