A lot of people won’t want to take much notice of Mary Bousted, joint-general secretary of the National Education Union (NEU), who warns today that schools face significant disruption by the end of September as Covid-prevention measures have to be reintroduced. It was the NEU, after all, which not only opposed the return of schools after the first lockdown, but simultaneously advised its members not to take part in online lessons either. The NEU has often given the impression of being motivated first and foremost by a desire to obstruct the government’s plans.

Sir Patrick Vallance’s original verdict on the virus – that it is not possible to stop it passing through the population – might be more valid now than it was in March 2020

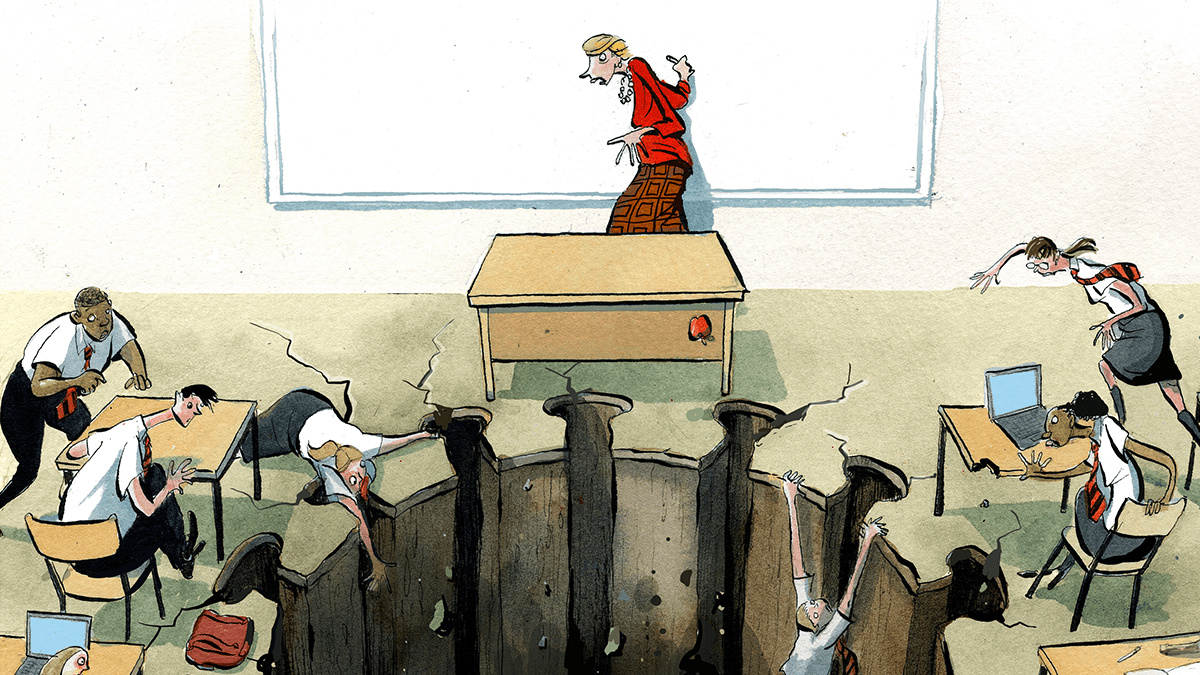

But Bousted has a point in that the return of schools over the next week could have quite a dramatic effect on infection numbers, which will test the government’s faith in controlling Covid through vaccines and travel restrictions, and will inevitably lead to calls for the return of tighter restrictions, perhaps even lockdowns. The warnings of what is to come are there to be seen in Scotland, where most pupils returned to the classroom in the week beginning 16 August. Since then, infection numbers in England and Scotland have diverged markedly. In England, 169,899 infections were recorded in the seven days to 9 August, followed by 174,551 in the seven days to 16 August, 185,903 in the week to 23 August and 174,760 in the week to 30 August. In Scotland the corresponding figures are 8383, 10,039, 21,164 and 37,917. The picture is complicated because the lifting of most restrictions – which happened in England on 19 July – did not happen in Scotland until 9 August. Nevertheless, it is not hard to see why schools might now be the epicentre of the epidemic. While most adults are now vaccinated, very few children are. In terms of the spread of the virus within schools, very little has changed since the first wave – except, that is, the more transmissible Delta variant is now dominant.

This week last year marked a turning point in Covid in Britain. The optimism which had reigned throughout August – the month of Eat Out to Help Out – rapidly evaporated as cases began to rise, leading first to the rule of six, followed by tiered restrictions and full lockdown by November. Was the return of schools to blame then? Not according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, which reported in January a study claiming that the autumn resurgence of the virus was more associated with the return of holidaymakers.

Nevertheless, the government is going to need a strategy to deal with a possible autumn resurgence, and to decide whether it is prepared to tolerate a wave of infections in schools. There are arguments for doing so. With most adults jabbed and hospitalisations and deaths still at low levels, there is a lot less justification for any restrictions than there was prior to the vaccination programme. Moreover, the way that the Delta variant has managed to get around tight lockdowns in Australia and New Zealand suggests that Sir Patrick Vallance’s original verdict on the virus – that it is not possible to stop it passing through the population – might be more valid now than it was in March 2020. Additionally, last week’s Israeli study suggesting that naturally-acquired immunity through infection might be stronger and longer-lasting than vaccine immunity can be used to argue for allowing the virus to pass through schools now, instead of winter when parents and grandparents might find their own immunity starting to wane.

But whatever it decides, the government needs to be prepared now in case infections surge, which seems to have followed the return of Scottish schools. As before, it may find itself having to fight off some of its own scientific advisers demanding tighter restrictions. One thing is for sure: whatever the merits of vaccinating under-18s, it could not now be achieved in time to prevent a resurgence in infections when schools go back.

Comments