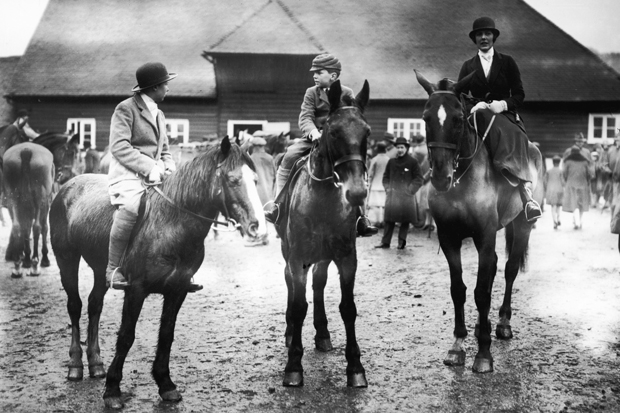

Mrs Christabel Russell, the heroine of Bevis Hillier’s sparkling book, was a very modern young woman. She had short blonde hair which she wore in two large curls on the side of her head, she was wildly social and she was a fearless horsewoman. In 1920 she set up a fashionable dress shop, Christabel Russell Ltd, at 1 Curzon Street.

At the end of the first world war she had married John Russell, known as ‘Stilts’ (he was 6’5” tall), the heir to Lord Ampthill, a cousin of the Duke of Bedford. His snobbish and crusty parents disapproved furiously of the marriage. The young couple spent little time together. Christabel, who adored dancing, went out night after night with one of her many admirers. Stilts was amiable but weak, and he sometimes appeared at parties dressed as a woman.

One day in the summer of 1921 Christabel visited a clairvoyant. To Christabel’s amazement, the fortune-teller told her that she was five months pregnant. Her doctors confirmed the pregnancy, but they also reported that she was a virgin. Instead of rejoicing at the news, the Russell family declared war on Christabel. John Russell sued for divorce, citing two named correspondents and ‘an unknown man’.

In court, both John and Christabel testified that their marriage had not been consummated. But Christabel denied the charge of adultery. She confessed to a horror of sex: though she admitted that 20 men had proposed to her, she hadn’t slept with any them. On the very rare occasions when she and John had shared a bed, and he had attempted what she called ‘Hunnish scenes’, she had pushed him away. The doctors, however, gave their opinion that it was medically possible for a woman whose hymen was intact to conceive through ‘incomplete intercourse’.

The details revealed in court about the Russells’ sex — or rather non-sex — life were so lurid that George V let it be known that he was ‘disgusted’, and the law was changed to prevent divorce cases being reported in the press. The Russell baby was nicknamed the Sponge Baby because some thought he was conceived as a result of Christabel washing with a sponge which had been impregnated by her husband. People joshed about Hunnish practices, and schoolgirls whispered that no girl should ever take a bath in water used by a man for fear of becoming pregnant.

Christabel was a natural courtroom star. Cross-examined by the legal grandee Sir John Simon she refused to be intimidated, parrying his hammer blows with witty and candid replies. It was a duel between two generations — the heavy-handed Edwardian versus the free spirit of the postwar bright (or not so bright) young things.

The jury disagreed as to whether Christabel had committed adultery with ‘an unknown man’, so the judge ordered a new trial. This time the Russell family hired Marshall Hall, the most famous barrister of his day and a master of courtroom theatre. For four hours he cross-examined Christabel. She admitted to a startling ignorance of the facts of life:

‘Do you know now that in moments of passion that portion of a man’s body gets large?’

‘I did not know that.’

‘Did you not know that that portion of a man’s anatomy becomes large and rigid?’

‘No, I did not know until you have just told me.’

‘What!’

‘How on earth should I?’

The Russells won the case — the jury found Christabel guilty of adultery with an unknown man and John was granted his divorce. But Christabel was having none of it. She appealed to the High Court, and when that failed she took her case to the House of Lords and won.

The Russell baby, whose name was Geoffrey, grew up to become a remarkably normal and sane human being. Christabel later granted her vindictive husband a divorce, and she understood that he accepted that Geoffrey was his son. But his family — who emerge exceedingly badly from this account — didn’t agree. John, who had become Lord Ampthill, died in 1973, and his family contested Geoffrey’s right to succeed to the peerage. They claimed that the rightful heir was John’s son by a later marriage. The disputed succession was heard by the House of Lords. The Russell baby case was fought all over again, and in the end the Committee of Privileges decided once and for all that Geoffrey was legitimate and the rightful heir to the title.

Today a simple paternity test would have saved all the expense and bother, but this courtroom drama is a thumping good read. As with all court-case stories, the book goes back and forth over the same ground a bit, but it is a riveting slice of social history. Bevis Hillier has done a brilliant job, and this book is both entertaining and definitive.

Comments