As part of the ongoing review into the primary and secondary school curriculum, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson has announced that children in England will be taught how to spot misinformation and extremist content online, so that students can arm themselves against ‘putrid conspiracy theories’. In the wake of weeks of rioting, with children as young as 12 and 13 now in court for their involvement, this announcement seems like a sensible idea, but it is not necessarily a straightforward one.

You simply cannot embed critical thinking without establishing a firm foundation of factual understanding first

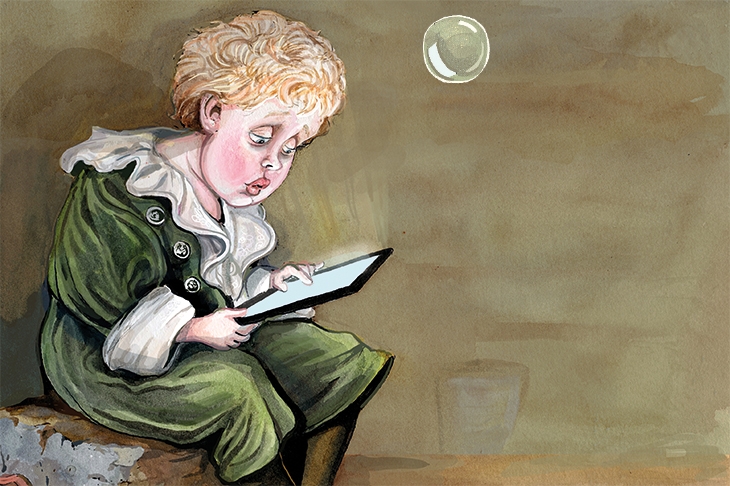

Children and teenagers are excellent targets for fake news, but they are notoriously bad at spotting it. Research by the National Literacy Trust suggests that the vast majority of students have heard of fake news, but when they gave students a quiz involving six news stories, only 3.1 per cent of primary school pupils and 0.6 per cent of secondary school pupils could correctly identify the four real stories from the two fake ones. Another study of 8,000 US students found that less than 20 per cent of 11 to 14 year olds seriously questioned spurious claims on social media, such as a Facebook post that said images of strange-looking flowers, supposedly near the site of a nuclear power plant accident in Japan, proved that dangerous radiation levels persisted in that area.

Everyone agrees on the importance of media literacy, and the idea that in an age in which everyone is a publisher, young people must be trained as consumers and creators of responsible content. The problem is how to do so. Digital literacy is already part of the school curriculum, and the importance of teaching about fake news has been raised by numerous education experts, such as Andreas Schleicher, director of education at the OECD in 2017; Education Secretary Damian Hinds in 2019, and Conservative MP Damian Collins in 2020. Yet little progress has been made, for two key reasons.

Firstly, we cannot keep adding to the curriculum without taking stuff out. Schools are constantly asked to teach more with less, and asking schools to teach something as nebulous, ever-changing and important as misinformation online is virtually impossible without proper time, training and resources. This squeeze also means that knowledge is being sacrificed in favour of other soft skills, but you simply cannot embed critical thinking without establishing a firm foundation of factual understanding first. For example, it’s no good teaching students that newspapers can cherry pick or manipulate statistics unless they have a solid understanding of things like percentages in the first place, whilst a discussion around anti-vaxxer theories is pointless unless they actually appreciate how vaccines work.

A lot of questioning of online sources also relies on common sense and cultural capital – for example, does a story match your prior knowledge, or seem realistic – which too many children lack, and therefore we overly-ambitiously expect them to be able to analyse what they cannot understand.

The second reason is that we end up in this postmodern practice in which, when looking at truth and fiction, we have to dismantle these ideas and definitions in the first place. For example, will students be taught to look behind labels such as ‘extremist’, and ask who is handing out that designation, and on what basis and with what bias? If not, many might worry, rightly, that students will not be taught how to identify reality, but only a government-mandated reality. What constitutes a respectable, defensible viewpoint can also change: for example, claiming Covid-19 was created in a lab in Wuhan, China was initially dismissed as a xenophobic conspiracy theory; then in 2021 Anthony Fauci, President Biden’s Chief Medical Advisor, admitted ‘the possibility certainly exists’. A WHO report deemed it ‘extremely unlikely’, but then backtracked that the conclusions were not ‘definitive’.

We also know that many adults struggle to identify misinformation, as recently evidenced by Elon Musk’s reposting of a fake Telegraph article claiming Keir Starmer was considering sending far-right rioters to ‘emergency detainment camps’ in the Falklands. This blunder shows just how difficult it is for schools to adequately prepare students for the Wild West of the online world. For example, many teachers will have told their students to think carefully about the reliability of their online sources by looking at someone’s credentials; a tweet from a pseudonym with no followers is more suspicious than someone who identifies themselves and has a larger following. Yet here we have Elon Musk, the literal owner of X with over 193 million followers, sharing fake news, which was seen by over two million people before it was deleted.

Of course, just because educating students on these matters is difficult does not mean we should not do it. But it is also important that the Department for Education appreciates the challenge of the matter at hand, so that schools feel adequately equipped to teach students about this brave new world, rather than just flippantly adding something else to teachers’ to-do lists.

Comments