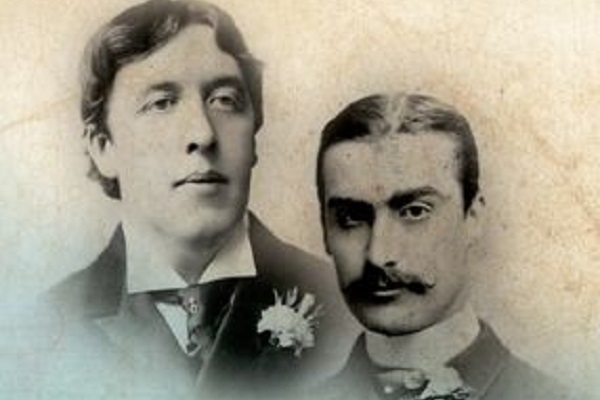

The life of Oscar Wilde is so wearily familiar that we assume that there is nothing new to think or say about him. This book proves us wrong. Carlos Blacker – the central figure of J. Robert Maguire’s research for more than half a century – rates, at best, a bare mention in Wilde’s many biographies. Yet, as Maguire conclusively demonstrates, he is no footnote.

Blacker, a handsome man of Latin extraction, knew Wilde in the days of his London pomp, was a witness at the writer’s wedding to the long-suffering Constance Lloyd, and often saw his friend on a daily basis. Wilde’s own testimony after his fall is ample evidence of their intimacy:

‘You were always my staunch friend and stood by my side for many years… Often in prison I used to think of you: of your chivalry of nature, of your limitless generosity. Of your quick intellectual sympathies, of your culture so receptive, so refined. What marvellous evenings, dear Carlos, we used to have!’

Blacker, like Wilde, was a married man with two sons; but, to avoid misunderstanding, it should be emphasised that theirs was not a sexual relationship and Blacker was resolutely straight. Nonetheless, Blacker was one of the small band who stood by Wilde before, during and after his trials, his imprisonment, and his subsequent exile in France.

What, then, marred this friendship? Maguire, a retired American lawyer, uncovers a very strange tale indeed. Wilde’s last years in Paris coincided with the notorious Dreyfus Affair — the mother of all political scandals that followed the conviction of an unpopular Jewish army captain, Alfred Dreyfus, and his exile to the penal hellhole of Devil’s Island off French Guiana on trumped-up charges of passing military secrets to Germany’s military attaché in Paris. Dreyfus’s family and a widening circle of radical politicians and journalists, rightly convinced of his innocence, campaigned to free him, while the army’s anti-Semitic high command worked with equally furious energy to doctor evidence and forge facts to keep Dreyfus rotting in his island cell.

Here, it would seem, was a case – analogous to his own – to snare Wilde’s interest, his sympathy, and his compassion. Yet, instead of joining his fellow writer Emile Zola in campaigning for Dreyfus, Wilde consorted with those who lied and cheated to keep Dreyfus incarcerated. Why?

The answer, it seems, lies in the writer’s fascination with the amoral ideas about sin and evil so brilliantly advanced in his novel ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’. Instead of joining the Dreyfusards, Wilde cultivated the company of the arch-villain of the Dreyfus Affair: Commandant Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, the man who had framed Dreyfus.

Soon after Wilde arrived in Paris on 13th February 1898, he met Rowland Strong, the Paris correspondent for the Observer, the Morning Post and the New York Times. Strong had been recommended to the impoverished Wilde as a possible source of funds. Strong may have had deep pockets; but he was also a fanatical anti-Dreyfusard. Strong was introduced to Esterhazy at the offices of the anti-Semitic ‘Libre Parole’ newspaper on February 14th 1898, and he introduced Wilde and Esterhazy shortly afterwards. The three men quickly became regular companions. Wilde spent night after night with Esterhazy in Parisian cafes, drinking and telling him that it was the metier of the innocent to suffer, and that, besides, guilt was so much more interesting than innocence.

Maguire has established that Blacker was convinced that Dreyfus was innocent and Esterhazy guilty because he had been so informed by his friend Alessandro Panizzardi, Italy’s military attaché in Paris. Panizzardi knew because his gay lover was none other than Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, the German attaché to whom Esterhazy had revealed the secrets. Blacker, who was conspiring to expose Esterhazy, confided this to Wilde when the two were reunited on March 13th.

The reunion with Blacker was a rare comfort for Wilde, who was often rebuffed by old friends during the last period of his life. He sought further meetings with Blacker over the next few weeks; but Blacker resisted, even when Wilde called for help following an accident. Wilde then betrayed Blacker’s confidence to Esterhazy in the presence of Strong and another journalist named Chris Healy.

Prompted by Esterhazy, the anti-Dreyfusard press had a field day. Strong’s New York Times printed the news (dated March 29th) on April 10th. Meanwhile, Healy fed the same information to Emile Zola, who wrote a piece for the Dreyfusard Le Siècle on April 4th. In time Zola’s article would be seen as a turning point for Dreyfus, but not soon enough to stop the blackening of Blacker’s name. The savage press reaction forced him into exile. He rightly complained of Wilde’s perfidy. Wilde denied the accusation and went on the attack. On 25 June, Blacker received a letter from Wilde saying that their friendship was at an end.

There were other elements at work undermining what Wilde called his ‘ancient friendship’ with Blacker, such as the disapproval of Carlos’s wife, Carrie, of the association. There is also Wilde’s displeasure with Emile Zola, who had refused to sign a petition for his release from prison, to consider. But Maguire is surely right to pinpoint Blacker’s horror at discovering Wilde’s frivolous, duplicitous and self-pitying nature – as the primary cause of the break-up. It is no wonder that this episode has been air-brushed away by Wilde’s admiring biographers, for it reveals him in his true colours, not on the bright white side of the angels, as we might wish, and not the scarlet and red of sin as he might have hoped, but a very queasy shade of grey.

————-

Nigel Jones is writing a study of 1914 for Head of Zeus and co-directs historicaltrips.com

Ceremonies of Bravery: Oscar Wilde, Carlos Blacker, and the Dreyfus Affair by J. Robert Maguire is publishing by Oxford University Press (£25)

Comments