The letter delivered last week to Mr Charles Salvador, of HMP Woodhill, from the parole board did not bring him the news he wanted – it said his request to be released from prison had been turned down. But the outcome came as no surprise to me, nor I suspect many of the others who had watched his parole hearing by video-link at the Royal Courts of Justice in London in March.

The conclusions that the parole panel reached were not rocket science, they were just common sense

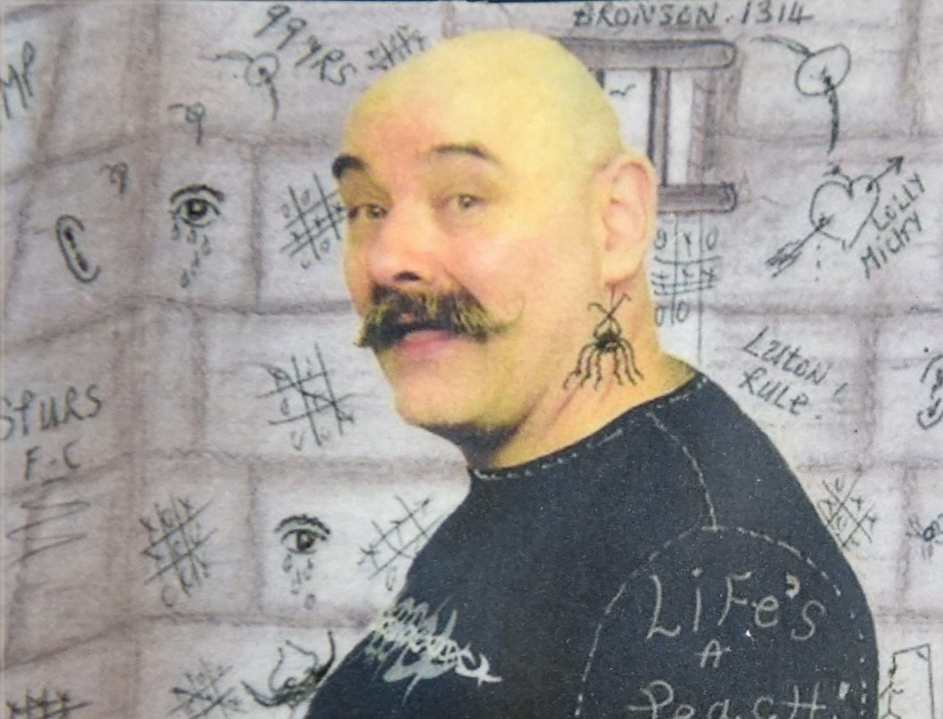

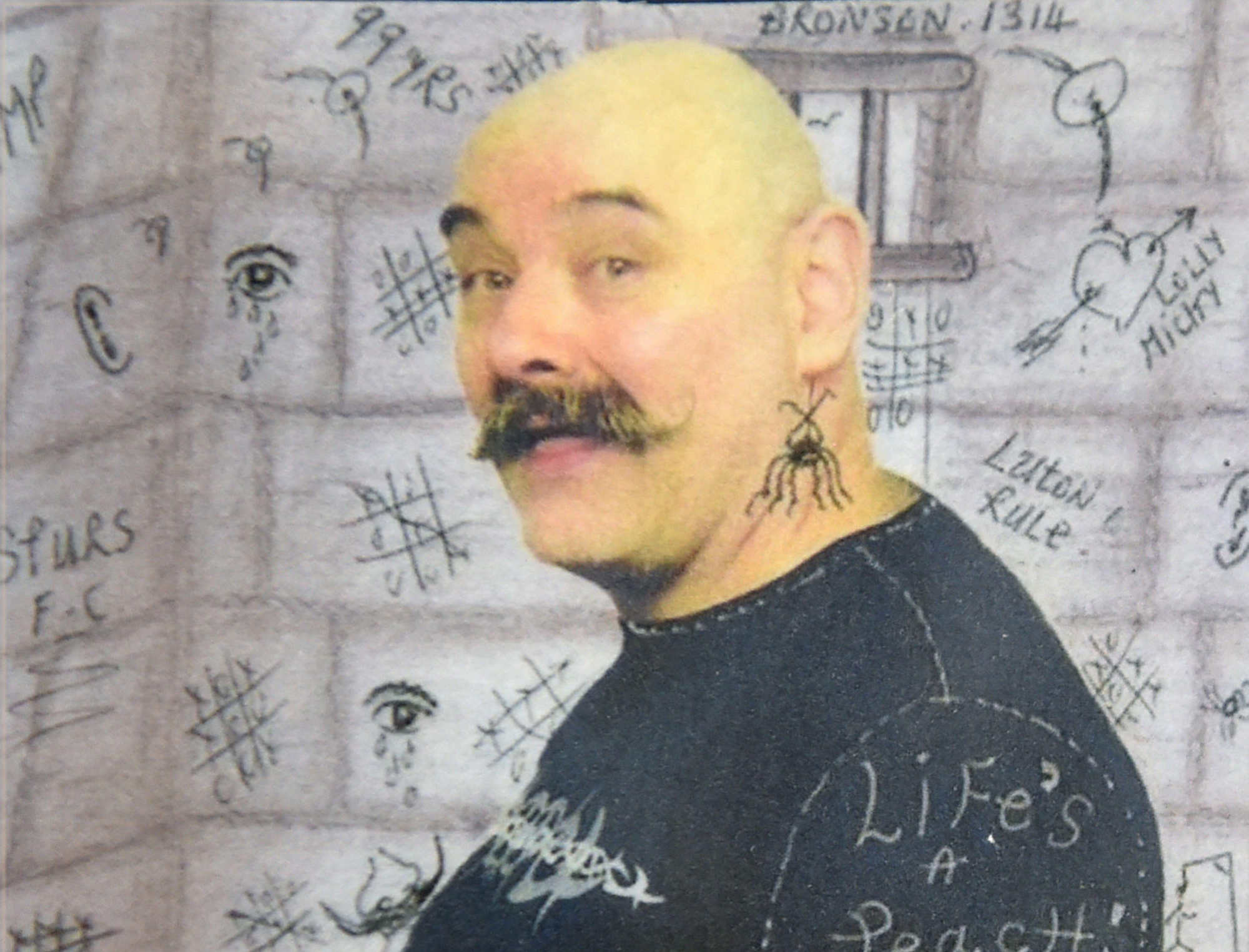

Salvador, whose birth name is Michael Peterson and who was previously known as Charles Bronson, has spent most of the past 50 years in custody. He has an appalling record of violence, including attacks on prison staff, and although there are signs he has mellowed in the last few years and is better able to control his anger and frustration, the evidence was clear: he is not ready to be let out of prison. The parole board said he was a persistent rule-breaker whose behaviour had been ‘callous’.

The three-member parole panel which heard the case also refused to recommend that the 70-year-old be transferred to a category ‘D’, or ‘open’ prison, with less stringent security and the opportunity to spend time in the community. Salvador is currently being held in Woodhill’s close supervision centre; he is locked in his cell for 23 hours each day and allowed to mix with just three other inmates, one of whom he doesn’t get on with. Any move to open conditions would have to take place only after he’d been tested for an extended period of time in a more normal prison setting.

The conclusions that the parole panel reached, therefore, were not rocket science; they were just common sense. Did it really require a three-day hearing – the eighth since Salvador has been in custody? Parole hearings are not cheap. In Salvador’s case, an extensive dossier was prepared for the panel members. Lawyers representing him, and the Justice Secretary Dominic Raab, were present throughout. Two psychologists, a probation officer, a prison officer and a friend of Salvador’s were called to testify; and at least two prison staff were in attendance for security reasons. It must have cost tens of thousands of pounds.

Prisoners serving life or an indeterminate sentence, as Salvador is, are entitled to a parole review once they have served the tariff, the minimum term of their sentence. If their request to be freed is denied there’ll be a further review within two years, and every two years after that if they are still in custody. Sometimes decisions are taken ‘on the papers’ by a parole board member, by analysing relevant information, but they frequently involve costly oral hearings. The number has almost doubled to nearly 9,000 a year since a ruling by the UK Supreme Court in 2013 emphasised the need for ‘fairness to the prisoner’.

That’s an important consideration but in Salvador’s case it would have made more practical sense for prison managers to get together to work out if he could be safely moved out from the close supervision centre and, if so, when and where. Those were not questions for the parole board to determine; its job was limited to considering release or a move to open conditions. Both are clearly a long way off.

During the proceedings, which at times bordered on the farcical, I kept thinking about the victims of Salvador’s crimes. One of them, former prison governor Adrian Wallace, reportedly told the Board that he still suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and flashbacks – 29 years after Salvador took him hostage. Have Wallace and the other victims been afforded a review every two years to see how they are coping and what support they might need? Of course not.

It is right that there are regular checks on prisoners’ progress in custody and efforts are made to rehabilitate and prepare them to lead a crime-free life in the community. But the perception, and I fear the reality, is that the needs of victims are not given as much attention, particularly in the long term. That is dangerous because it chips away at confidence in the criminal justice system. Measures announced in the Victims and Prisoners Bill, to bolster victims’ rights, do not go nearly far enough.

To the parole board’s credit, it allowed Salvador’s case to be screened to the media and some members of the public, as it did with Russell Causley’s parole review last December, and gave the BBC access to hearings for a TV series which has been shown this year. It has shone a light on a vital part of the criminal justice sector that previously existed in the shadows, highlighting the meticulous way in which parole panels go about their work. If only other justice agencies were as transparent.

But the coverage has also raised serious questions about the way the parole board operates, not least whether reviews every two years are always necessary and if so many hearings are required. It might help the board to draw up plans for a more focused role – triaging cases more effectively to target resources and expertise where prisoners have a real prospect of release, rather than a theoretical one.

Being proactive by developing its own ideas for the future could stave off the very real threats to the board’s independence from proposals in the new Bill which would give the Justice Secretary a veto over release decisions in high-profile cases. The plans risk politicising the parole process and adding an unnecessary layer of complexity to it. They are a distraction from the real problems in the system – delays in criminal investigations, court backlogs and a shortage of prison places – the lingering consequence, among other factors, of budget cuts during ‘austerity’.

But unless there’s a snap election or the Bill runs out of parliamentary road the parole changes will almost certainly become law – just in time for Charles Salvador’s next bid for freedom.

Comments