David Cameron probably didn’t need reminding while he was in China what fools intelligent people can be when they visit authoritarian regimes.

David Cameron probably didn’t need reminding while he was in China what fools intelligent people can be when they visit authoritarian regimes. ‘Useful idiots’, as Lenin didn’t say, they make allowances for dishonesty, even horrors, which they never would at home, express guilt for the past of their own countries, use words like ‘progress’ for the place they are briefly visiting, and accept at face-value hospitality and words which normal consideration would tell them were well-rehearsed and manipulative.

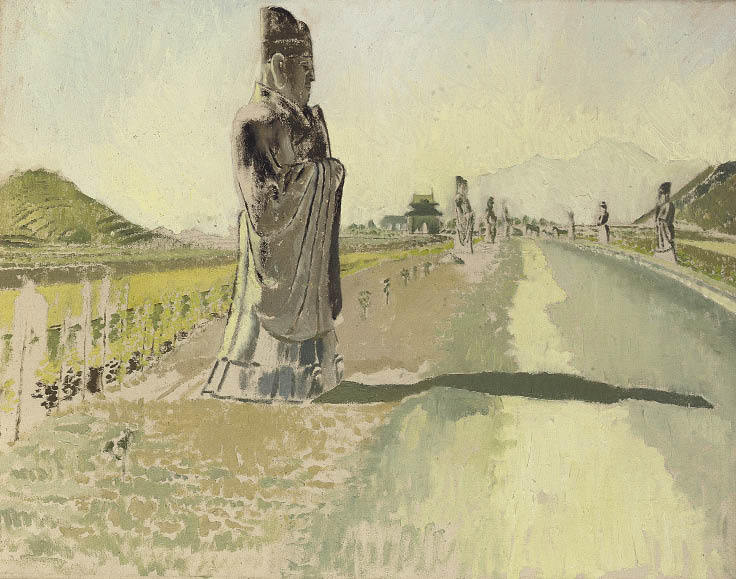

Patrick Wright, a journalist and historian, describes the three ‘missions’ to China in 1954 to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Communist victory. The first mission, a high-powered Labour Party group, headed by Clement Attlee and Aneurin Bevan, met Chou Enlai and had an audience with Mao. The second mission, a ‘cultural delegation’, included Hugh Casson, Paul Hogarth and Stanley Spencer, who produced a number of paintings and sketches. These, especially Spencer’s, strike me as excellent, and show what an observer, even in China, could do if allowed to use his talents without reinterpretation by his hosts. Hogarth, however, later ‘repudiated his drawings’. The third mission included many trade unionists and, as adviser, E. G. Pulleyblank, the Professor of Chinese at Cambridge.

Passport to Peking is far too long and disjointed (it winds through almost a third of its length before the travellers reach China), and is not the ‘desperate comedy’ Wright thinks. But it painfully reminds me of a similar ‘mission’ to China in 1972, one of the first American ones, even before Nixon. My fellow trippers, all PhDs in various Chinese subjects, were, like those in 1954, bowled over by the assurances, banquets, smiles, friendly children, spotless factories, hospitals and cheerful peasants. We, too, were charmed out of our minds by Premier Chou Enlai, who told us four hours’-worth of lies and watched his guests lap them up. At least, unlike some of the 1954 trade unionists, we didn’t besiege Chou for his autograph.

Wright pads out his book with pages on Chinese history since the 19th century, American McCarthyism and British attitudes to Mao’s China. His history is over-simplified and out of date, and some of his sketches of China-experts like Edgar Snow are incomplete. He may not know that Snow consulted the American and Soviet Communist Parties on what attitude to take towards Mao when he wrote Red Star Over China in 1937, and with their advice ‘corrected’ some politically unacceptable comments for his second edition. Wright lists some of the British intellectuals eager to sign ‘letters of friendship’ — not just enthusiasts, like J. D. Bernal, Hewlett Johnson and Joseph Needham, but E. M. Forster, Henry Moore, Siegfried Sassoon, Eric Gill, Arthur Waley and J. B. Priestley all showed themselves keen to support a regime that had executed tens of thousands of landlords and killed British soldiers in Korea.

These ‘friends’ of China in the 1950s swallowed the same hokum as their French counterparts — about whom Richard Wolin has so tellingly written in his recent The Wind from the East: French Intellectuals, the Cultural Revolution and the Legacy of the 1960s. (Years later, when I asked Needham, a fine scientist, if he still believed that the Americans had used germ warfare in Korea, as he insisted for years, he told me he trusted his Chinese informants.)

The trippers paused in the Soviet Union; Stalin had died the previous year. Untroubled by the effects of his rule, although his record was already well known, they were dazzled instead by the ballet and the Moscow subway, and drank regular vodka-fuelled toasts. In China, too, apart from occasional niggles, little disturbed them, and certainly nothing about Mao, whom some of them met with pleasure. In 1954 the Chairman, who would have even the notoriously paranoid President Nixon eating out of his hand in 1972, assured Bevan, who asked about land collectivisation, ‘It will be many years, perhaps scores of years, before we bring it about.’

It was brought about two years later. In Russia, one of the biggest saps, Cedric Dover (who at one point had admired Hitler for his ‘biological approach’), observed that during Stalin’s show trials

the anti-Semitic serpent has failed to even wriggle its tail. In the recent trials many of the principal defendants were Jews, yet there was not the slightest whisper within the country of a Jewish plot.

Chou Enlai, who lied amiably and smoothly to my group in 1972, did the same with one credulous mission in 1954. Asked about religious freedom in China, he ‘cited the presence of the Dalai Lama in Beijing as proof that freedom of worship was of course accepted in the new China.’

The 19-year-old Dalai Lama was indeed in Beijing; J. D. Bernal, who sat next to him as they both drank orange juice, asked him nothing. The Dalai Lama records in his autobiography that, near the end of his visit, Mao told him that Buddhism would be extinguished in Tibet. The Dalai Lama wrote that he suddenly knew he was in the presence of ‘the Destroyer’.

Bernal, who spent much of his life as a distinguished scientist flacking for the Communist camp, watched Mao’s smiles on China’s National Day, and concluded they were

the most intimate linking of the people with their leader … He does not even need to say very much; he just smiles, and the people know what he had done and what he is doing.

Wright provides an amazing fact about the Attlee mission. Before it left Britain it had been supplied with a Memorandum on Repression and the Forced Labour System in China by the Labour Party’s own international department, plus information from 21 émigrés from China; while the visitors were in Beijing a British embassy officer, Humphrey Trevelyan, urged them to be suspicious about what they were not seeing. According to Wright, when challenged years later about being ‘useful idiots’ in China, two visitors, one of whom was Barbara Castle — who must have read the memorandum — dismissed criticism of the mission as being ‘launched from the pulpit of hindsight’, which had failed to grasp that ‘1954 in China was a time of real potential’.

When he was Prime Minister, Attlee had been vigorously anti-Soviet; but in China he was knocked off his pins by his cannily hospitable hosts. He told the Labour Party conference that September that ‘the Chinese, with their great traditions, would not fall for the cruder forms of Communism’. Hugh Casson, one of Britain’s top public intellectuals, would muse: We see what we see … Is what we don’t see, or even what nobody can see, more significant?’ Casson went on to say that to show respect to one’s hosts it was necessary to ‘accept’, inter alia,

the distortion of truth, the insistence upon official infallibility, the mutual suspicion and informing, the need for the accused to prove his innocence and not the accusers his guilt.

When they returned to Britain, Casson, A. J. Ayer and Professor Leonard Hawkes wrote in the Manchester Guardian that they had not been asked a single political question in China:

Was that not a bit odd? Well, they were hosts; we were guests. No, we did not ask a single political question either — perhaps that was a little bit odd, too.

Comments