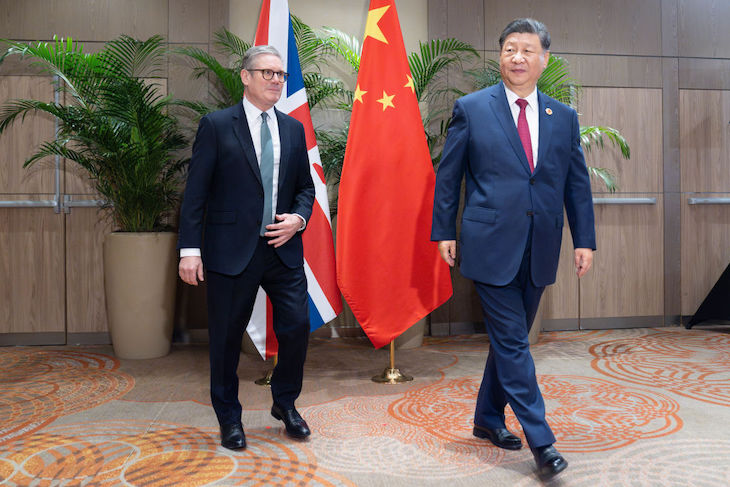

When Dominic Cummings claimed this week that China had hacked into Britain’s most secret systems, the government rushed to deny it – understandably, given the political heat over the collapsed Chinese spy trial. But even if Cummings’ story proves false, the underlying truth remains: China has been systematically targeting Western networks for years, and extracting vast quantities of sensitive information. What is striking is not the allegation, but the reaction by a government so anxious not to call China a threat that it pretends not to see one. It is a surreal position, because the danger has been obvious for years.

The truth is that China poses a greater strategic threat to Britain than any state since the Second World War

The truth is that China poses a greater strategic threat to Britain than any state since the Second World War. It is not just a rival economy; it is an adversarial system seeking to rewire global power to its own advantage. And Britain, almost uniquely among the major democracies, still pretends that it can manage the danger with a few polite euphemisms.

China’s first weapon is economic. For two decades, Beijing has practised what might be called mercantilist innovation – the deliberate fusion of industrial espionage, state subsidy and global dumping. The formula is simple: acquire (sometimes, but not always, through theft) Western technology, turbocharge it with massive subsidies and cheap credit, and flood the world with exports that undercuts, and eventually destroys the opposition. A particularly relevant example when it comes to this government’s net zero aspirations is the solar-panel industry, where Western intellectual property was copied, production shifted to China, and foreign manufacturers wiped out.

This is not the natural rhythm of globalisation; it is a form of economic warfare. China’s dominance of solar, batteries, and telecoms has been achieved not by competition but by manipulation – a systematic transfer of Western know-how into state-directed conglomerates. Former FBI director Christopher Wray called China’s targeting, particularly of the US, as ‘one of the largest transfers of wealth in human history’.

The second threat is ideological and systemic. China’s leaders do not accept the legitimacy of the liberal international order built after 1945. Chinese leader Xi Jinping speaks openly about creating a ‘new global order’ that reflects ‘the realities of the new era’ – code for one where the West no longer writes the rules. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the expanded BRICS bloc, Beijing is constructing an alternative world of finance, standards, and diplomacy, in which law yields to hierarchy and markets yield to politics.

For Britain, this is not abstract. Our prosperity and influence rest on an open, rules-based system that assumed that contracts will be honoured and trade routes will remain free. China’s model is transactional: obedience first, opportunity later. A world remade in Beijing’s image would leave Britain diminished, its companies sidelined, its diplomats excluded, its voice irrelevant.

The third threat is dependency. It is an astonishing but undeniable fact that Britain cannot currently rearm or decarbonise without China’s consent. Every advanced weapon – from missiles to radar to fighter jets – depends on rare earth elements, magnets and specialty materials overwhelmingly produced in China. More than 80 per cent of global rare earth processing capacity sits under Beijing’s control. The same applies to renewable energy: China dominates 70 per cent of the world’s lithium refining and more than 80 per cent of solar manufacturing.

This is not interdependence; it is strategic leverage. In any future crisis, Beijing could throttle our industrial and energy base at will. The Ministry of Defence’s ambitions to ‘rearm at pace’ and the Department for Energy’s green transition both dangerously rest on Chinese supply chains. Despite years of warnings, Britain still has no credible programme of mineral stockpiling, no industrial strategy for substitution, and no serious plan for allied sourcing.

Given these realities, why does the government still refuse to call China a threat? The first reason is economic delusion. Ministers still cling to the idea that China represents a vast commercial opportunity. In truth, it doesn’t. Very few foreign companies make durable profits there; intellectual property is extracted, markets are manipulated, and contracts are enforced only when convenient to China. Britain’s exports to the People’s Republic account for just 3 to 4 per cent of the total – less than we sell to Ireland or the Netherlands. Yet the myth of Chinese indispensability endures.

The same wishful thinking infects investment policy. Successive governments have courted Chinese capital for nuclear plants, energy grids and real estate, mistaking scale for virtue. But the question is not whether China can invest in Britain, but why we would want it to. There is no shortage of allies –Japan, South Korea, the United States, Europe – eager to invest in a stable, law-abiding market. The argument for Chinese money has always been a mirage.

The second reason is fear. Ministers are paralysed by the thought of Beijing’s anger. They have seen what happens to countries that cross China: Australia hit with tariffs on wine and barley; Japan cut off from rare earths; Norway punished for awarding a Nobel Prize to a dissident. So they whisper the word ‘threat’ in private but never say it in public, hoping to avoid retaliation.

Yet this logic is precisely backwards. If China is willing to use coercion against middle powers – who, we should remember, are in the main our allies – that is the strongest reason to harden our economic defences. This means building resilience and stockpiling critical minerals. Instead, the UK has chosen inaction. It neither confronts China nor prepares for coercion. The result is paralysis: a policy that offends our allies and reassures no one.

Britain’s China stance now combines the worst of both worlds

Britain’s China stance now combines the worst of both worlds. The government is too timid to deter, and too complacent to prepare.

China is the defining strategic challenge of the twenty-first century, and for Britain it is a direct and growing threat. It appropriates our ideas, undermines our industries, shapes the world order to its advantage, and holds the means to throttle our rearmament and our energy transition. And still, ministers dither.

This is not prudence; it is appeasement masquerading as nuance. A serious government would use the present calm to rebuild resilience, diversify supply chains, and align with allies on a coherent strategy. Instead, Britain has drifted into strategic denial – a country that cannot even name its greatest adversary for fear of causing offence.

It is, quite simply, a dereliction of duty. China really is a threat to the United Kingdom, and the longer our leaders pretend otherwise, the weaker we become.

Comments