The only MP I have ever really wanted to marry is Thangam Debbonaire. The former Labour MP for Bristol West and I have little in common. But it has sometimes been a desire of mine to marry her and take her surname, so becoming Mr Debbonaire. Marital relations would doubtless be fraught, but on the plus side there would be the thrill of friends being able to say things like ‘Darling, you know the Debbonaires are coming for dinner?’ Which would more than make up for it.

Since being booted out by the voters at last year’s general election, Debbonaire has been elevated to the House of Lords, where she still attracts my attention. In an interview on the BBC’s Newsnight at the end of last month, shewas so fantastically aloof towards the concerns of the public – and any viewers – that it seemed becoming Baroness Debbonaire had rather gone to her head. As indeed it would to mine.

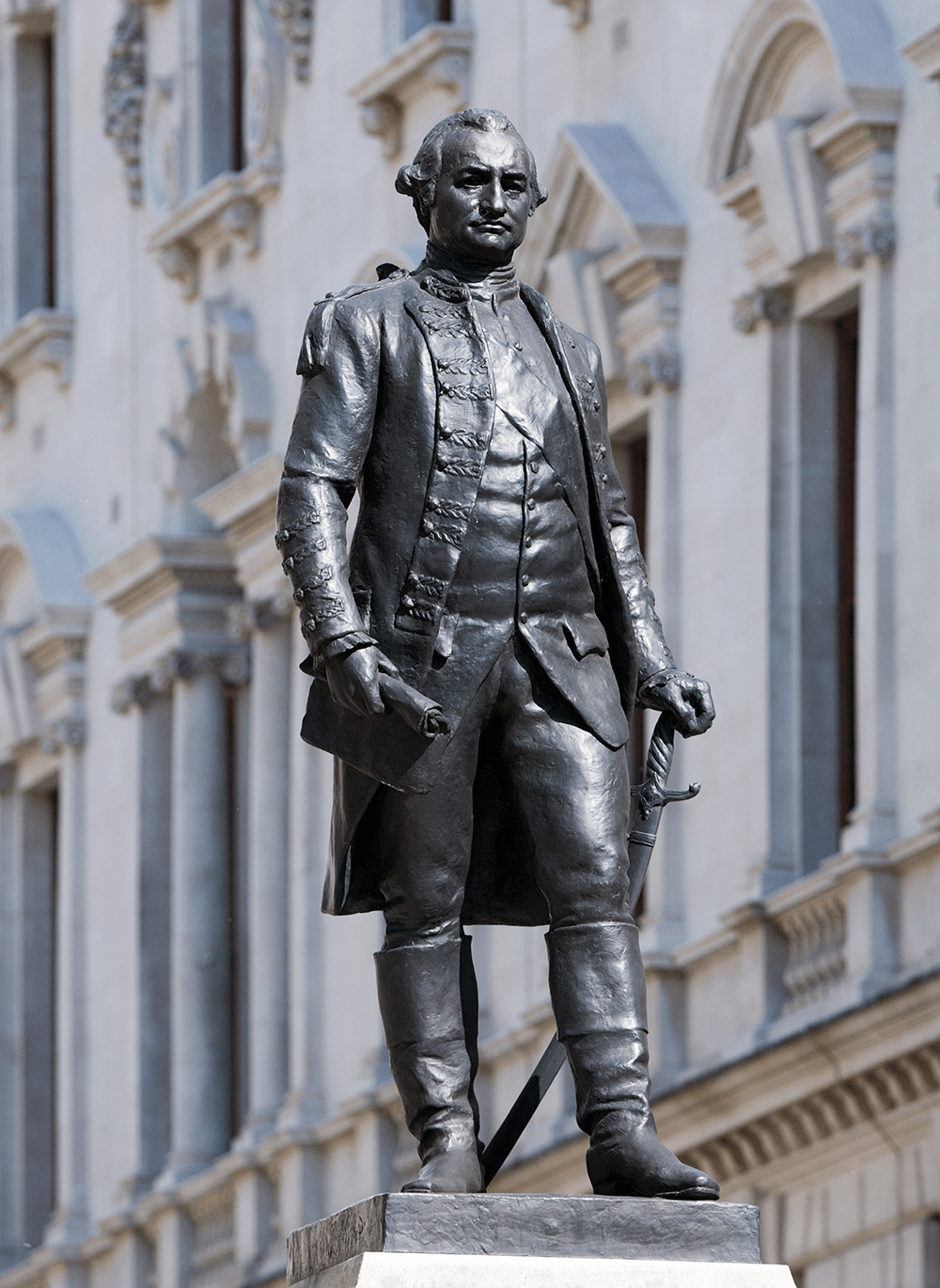

Anyhow, the noble Baroness was back in the news in a small way this week when she used the Edinburgh book festival to call for the removal of the statue of Clive of India from its magnificent position outside the Foreign Office. Clive appears to be guilty of that most common of modern crimes: being found to have lived in the past. As a result, he can now be added to the ‘Wanted’ list of statuary which, by my reckoning, has in recent years included almost every figure honoured in Trafalgar Square and indeed everywhere else in the country.

Debbonaire must know where this type of talk can lead. She was an MP for Bristol when the locals of that city – and a few outsiders – decided to take things into their own hands and tear down the statue of the local slaver and philanthropist Edward Colston.

You get the strong impression from such people that if they had their way they would follow the example of American cities such as Portland, Oregon and Richmond, Virginia. After the great outburst of iconoclasm during the past decade, Portland has become a terrific city to visit if you have a deep interest in empty plinths. Monument Avenue in Richmond now has only one monument on it – a statue of the late tennis player Arthur Ashe. That was erected in 1996, but doubtless it too could come down some day, not least because it gives off the unfortunate impression that the child kneeling at Ashe’s feet is about to be harshly beaten by him with his raised tennis racket.

He appears to be guilty of that most common of modern crimes: being found to have lived in the past

Those who call for the removal of historical monuments always do so for the same reason: the figures being honoured should not be honoured because they did something dishonourable. The people telling us this insist that we should teach a different version of our history. When pressed, they generate a distinct suspicion that the version of our history they would like us all to imbibe is their own version.

Nonetheless, they are winning the argument. A YouGov poll published earlier this year found that young Britons are the group most likely to take a negative attitude towards the British Empire as a whole. Indeed they were the only cohort of voters whose most common answer regarding their attitude was that the Empire should be ‘a source of shame’. This, incidentally, was an increase of almost 10 per cent since the question was asked just six years ago.

So Baroness Debbonaire and others should probably be happier than they are. They are getting their way. But I do wonder what sort of people will be created in this new iconoclastic era. Personally, I prefer the sort that we used to produce. I used some downtime this week to read the recently published diaries of Peter Kemmis Betty (Half a Banana, Charlcombe Books). Kemmis Betty was a Gurkha officer imprisoned in the Japanese Changi prisoner-of-war camp between 1942 and 1945. Having written and kept the diaries at considerable risk to himself, he relates plenty of the horrors that he and his fellow prisoners went through – including their discovery of what had happened to their fellow PoWs a little way up the road on the Burma railway.

The thing that really stands out about the diaries are the accounts of how the British prisoners manage to get through their time in the camp. They arrange a series of talks to keep each other entertained and educated. They set up a choir. They put on theatrical productions of plays by George Bernard Shaw and Noël Coward. One inmate, who was previously a violinist in the London Philharmonic, gives a performance of Beet-hoven’s Violin Concerto in D.

The days are long and the suffering terrible. The prisoners try to supplement their food by arranging a system of gardening. Makeshift sheds in the camp are used as chapels, with one padre internee saying afterwards how many of the PoWs stated it was ‘the sacraments and services of their churches which kept them sane, when everything men hold dear was lost’.

If the phrase ‘mustn’t grumble’ could be summed up in a diary, it is here. But it got me thinking again about those attitudes, manners and characteristics we used to take for granted as being distinctly British. They are the sort of traits that some of us grew up with. And it seems to me that they are among the less tangible things to be lost when you wage war on everything in your past so gleefully.

The eagerness to condemn our past seems particularly acute at the moment. Yet all attempts to replace that past are so thin that nobody can even define them except in the most anodyne and meaningless fashion. Britishness is now said to be about kindness and tolerance. Fine things, but they only get you so far. The question of whether they would get us through the sort of trials our forebears went through is a question I suppose only time will answer.

Comments