This handsome and encouraging book is perhaps unfortunate in its title. The suggestion is that the author has been forced to rummage among the wreckage that is England in order to find something, anything, that is still intact. Its origins and intentions are quite the opposite.

As Richard Ingrams explains in his short introduction, when he was editor of Private Eye he published a regular feature called ‘Nooks and Corners of the New Barbarism’, written by John Betjeman — a suitable kind of investigation for a satirical magazine. When, in 1992, he founded The Oldie, a feature called ‘Unwrecked England’ written by this author, Betjeman’s daughter, was precisely intended to redress the balance, to express enthusiasm, and this is what her Oldie pieces collected here triumphantly do. Caught on the journalist’s tag of her column’s title — which Oldie readers will recognise and rejoice at — a wider readership, which it deserves, might be deceived.

The 100 articles here, a selection from 25 years of enjoyment, do not merely celebrate little pockets of beauty that have somehow survived. They express a continuity, under threat of course; everything always is and always has been. If it isn’t the Scots or the Norsemen it’s the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Industrial Revolution, the Age of the Motorway, or sheer human wrong-headedness. They all give evidence of an instinct for survival that seems almost miraculous. This is a greatly cheering book, written with charm and containing great photographs.

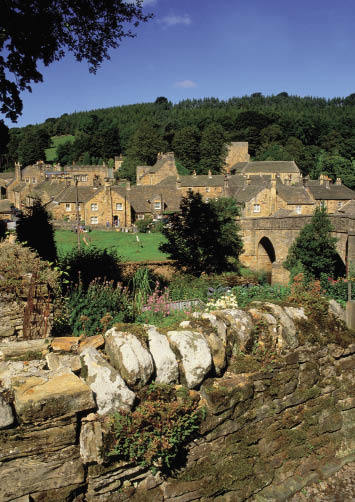

No piece is without its enlivening anecdotes. Blanchland, for example, in Northumbria (the places are in alphabetical order) was so out of the way in the 14th century that a band of Scottish marauders failed even to notice it. To celebrate their deliverance the monks rang a peal of bells and the Scots returned to sack the place. John Wesley in the 18th century found it ‘little more than a heap of ruins’. About the same time Lord Crewe ‘made a packet from the surrounding lead and coal mines — he wanted to see his workers living in decent housing — and created what is one of the greatest planned villages in England.’ Now, there’s a heartening tale. ‘The scale of it all feels utterly comfortable, and the enclosure creates a kind of magic.’

Nevertheless, it is still out of the way, and here perhaps a word of caution. Lycett Green declares herself ‘too lazy to walk’ and seems to have done most of her exploring on horseback. Of course we don’t have to do that, we can get there by car, but she often suggests that the best way of approach, in order to surprise ourselves, is slowly. It is a question of tempo: you can’t just jump out of your car, have a look and drive on. Her form of transport makes it easier for her to savour, notice, take in. We can do that too, but it takes time. That is what Lycett Green gives her discoveries, time: in fact she blesses her editor, Richard Ingrams, for paying her to do what she loves best, exploring her beloved England as her father and mother taught her to do, admittedly by car, when she was a child.

Anyway, you don’t have to go by horse to see Liberty, the shop in London. Its mock-Tudor facade was built from the timbers of HMS Hindustan and HMS Indomitable:

The frontage on Great Marlborough Street is the same length as the Hindustan… Harrods was always too big for me to handle, but Liberty — ah, Liberty! … Many of the rooms had fireplaces, some of which still exist … To travel in a panelled lift to the Needlework Department is comforting beyond compare.

Southend, Wilton Music Hall, the Pack- horse Inn, Stanhope (a Victorian working village, whose beauty lies in its being so wholly itself, unpretending), Torquay, so elegant, so genteel that Rudyard Kipling exclaimed, ‘I do desire to upset it by dancing through it with nothing on but my spectacles’: Lycett Green finds beauty, resonance and history in them all, as well as ‘comfort’.

The last entry is perfect for the finale: Wreay, Cumbria, again out of the way. A lovelorn Victorian lady rebuilt the church with estate labour and with decoration by local craftsmen, and it looks wonderful:

Sarah Losh was simply half a century ahead of her time with her brave new style and her wild imagination. Not everything has to be put in a box. I am glad Wreay is out on a limb.

Comments