What does the coronavirus crisis mean for unemployment in the UK and Europe? A study out today from Capital Economics offers a possible answer and if it’s bad news for Britain, its worse for those in the eurozone.

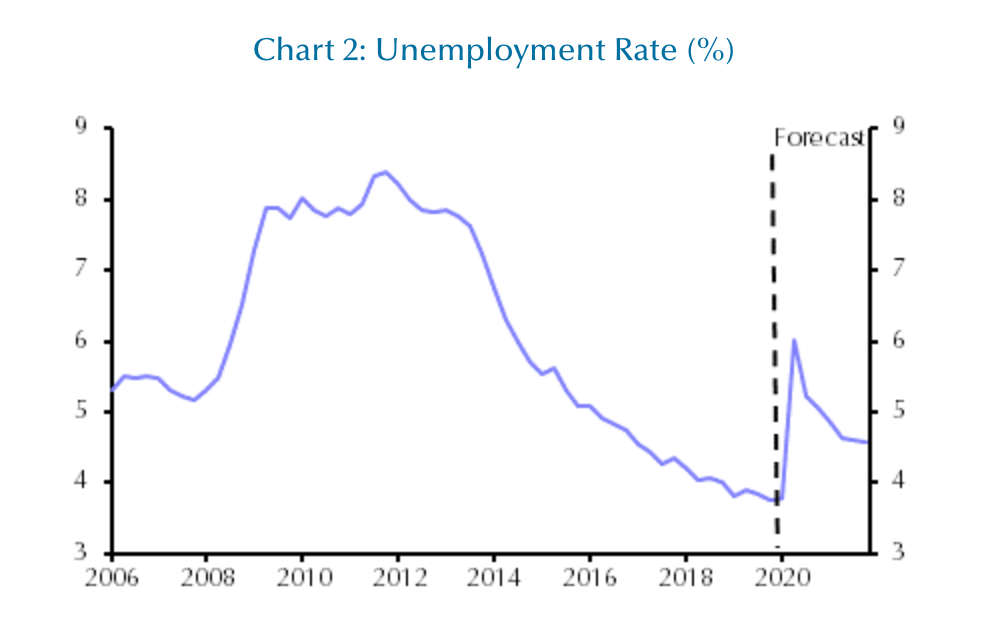

Here in Britain, the huge economic consequences spurred on by the virus – which will see growth plunge in the second quarter of 2020 – are estimated to cause a sharp, albeit short, spike in unemployment: an estimated rise from 3.9 per cent to six per cent; roughly 700,000 job losses:

Capital Economics considers several factors when calculating these new unemployment projections, including a lower number of total hours worked in the economy during the Covid-19 crisis, and how this work is split between people reducing their hours or becoming unemployed all together.

This research supports the evidence we’ve already seen that job loss is becoming sharp and sudden (in just four weeks, 200,000 people in Britain’s leisure and hospitality sectors have lost their jobs). Notably, however, their rate prediction stops short of the eight per cent unemployment peak reached during the global financial crisis. This is largely because new demand for workers in some areas (including food and delivery companies) is off-setting job losses in other sectors. Furthermore, the Treasury’s ‘wage guarantee’ for salaried employees is thought to be a blunt but effective tool to keep many in their jobs for a while at least.

Meanwhile in the eurozone, the figures look increasingly grim. Capital Economics estimates that the unemployment rate will double that of the UK’s: skyrocketing to roughly 12 per cent in the next three months. This surge translates to ‘giving up seven years’ worth’ of employment gains made after the financial crash, and will come close to its record-high unemployment rate experienced during the euro-zone crisis.

There is potentially light at the end of the tunnel: both the UK and the eurozone, the research suggests, will see their employment rates start to tick back down fairly quickly. If new predictions about a V-curve recovery prove correct, the economy should jump back into action just as quickly as it fell off a cliff, creating a booming demand for services, and as a result, a demand for jobs as well.

But yet again their is a big catch to these employment predictions: they assume the economy can get back on track soon, because the virus is quickly tackled. As today’s studies – and all emerging economic and employment models – are quick to point out, these assumptions are still far from certain.

Comments