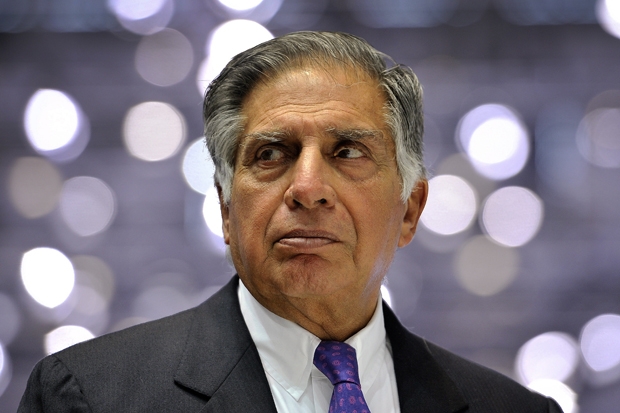

If asked to pick the UK’s inward investor of the century so far I would, without hesitation, name Ratan Tata, the anglophile former patriarch of the eponymous Indian conglomerate that bought Tetley the tea-maker for £271 million in 2000, Corus the Anglo-Dutch steel-maker for £6.2 billion in 2007, and Jaguar Land Rover — from Ford — for £1.3 billion in 2008. We’ve heard a lot lately about Mr Tata’s hubristic folly in buying Corus in the first place; and about his boardroom successors in Mumbai ‘going through the motions’ of finding a buyer for Corus UK —with its Port Talbot blast furnaces symbolising what’s left of our shrunken industrial heritage — while secretly aiming to shut it down to protect Corus’s more modern plant at IJmuiden in Holland, which Tata plans to merge with ThyssenKrupp of Germany, creating a Fortress Europe steel giant to resist the Chinese.

That’s all been made to sound quite sinister, highlighting the peril of relying on footloose foreign capital. Meanwhile David Cameron and out-of-his-depth Sajid Javid are desperate to avert closure of Port Talbot before the EU referendum date in June, lest blame for job losses converts to votes for ‘leave’. But let’s pause amid the frenzy of spin to give credit to Tata where it’s due.

It’s true that the Indians overpaid wildly for Corus, without much due diligence, in a late-night live auction against the Brazilian bidder CSN in which Corus’s advisers could barely believe their luck; and that Tata has failed to make UK Corus viable in increasingly adverse global market conditions. It also happens to be true that Tata underpaid by a wide margin for Jaguar Land Rover (if the prices of the two had been swapped, they would have looked about right) and went on to work miracles with it.

Under Ford’s ownership, JLR had come close to collapse, making barely 150,000 cars a year. Since then, Tata has invested more than £11 billion in a business which last year made almost half a million cars (surpassing Nissan’s UK output), of which 80 per cent were exported, with China as the major destination. JLR’s workforce has doubled under Tata to 35,000 — meaning that it has created more skilled jobs in car-making, which has an exciting future, than it may be about to shed in steel-making, which doesn’t. The ‘JLR effect’ radiating from its plants at Solihull and Castle Bromwich has revivified a swathe of the West Midlands economy. So let’s hear no criticism of Tata as an inward investor: business schools the world over now use JLR as a case study of how it should be done.

But why the failure with Corus? Because the steel price plummeted, as we know, thanks to dumping of surplus output by the Chinese to whom UK ministers have so slavishly kowtowed to such negligible benefit. But also because Port Talbot is too small (half the capacity of IJmuiden), too old, in the wrong place, reliant on fickle customers, laden with environmental problems, and incapable of winning sufficient export orders to replace shrinking UK industrial demand. Whereas JLR had valuable marques that just needed capital to make them flourish, Corus had 50 years of bad history and few if any natural advantages.

Saleable pieces

That’s not to say that there are no saleable pieces of Corus and no future for UK steel, albeit small-scale. The historic Scunthorpe works, which chiefly makes rails, has found a private-equity buyer — and if I were a bold investor I’d be taking a look at the Shotton plant in North Wales, producing galvanised and colour-coated sheet and coil. Otherwise, hope rests on Indian-born Chepstow resident Sanjeev Gupta, who is buying two Corus mills in Scotland, has other steel interests in Wales, and has been persuaded to express interest in taking on the whole mess, including Port Talbot. But why would anyone do that, except in a deal massively sweetened and underwritten by panic-stricken ministers?

As for Tata’s contribution to the UK economy, their outstanding success with JLR far outweighs their naive and costly failure with Corus. As one insider told me this week, ‘You could say hats off to them for sticking with it as long as they have.’

Good and bad balance

Should we worry about the balance of payments? Yes, though perhaps not as much as we should worry about Helen in The Archers. Our current account deficit for 2015 was £96 billion, or 5.2 per cent of GDP — the worst since records began in 1948. But within that, the deficit in goods and services was £37 billion (still cause for concern, but relatively steady at 2 per cent of GDP) and much of the rest was to do with imbalances of investment income: foreigners receiving fatter dividends on their investments in the relatively healthy UK economy than we receive on ours in underperforming parts of the world such as the eurozone. So on balance, it’s not such a bad problem to have.

The client list

Let me make this perfectly clear: I have never asked Mossack Fonseca of Panama to set up a company for me in the British Virgin Islands or anywhere else. At least I don’t think I have: I mean, who reads the small print of all that boring paperwork from wealth managers and accountants these days? Among 11 million leaked Mossack Fonseca documents, we will probably all find our own names somewhere, plus those of Elvis and Lord Lucan. Even so — and leaving aside, for today, the morality of offshore tax structures — we can admire the breadth of the Panamanian law firm’s client list, stretching as it reportedly does from ‘senior Tory peers’ and a cousin of Bashar al-Assad to the brother-in-law of the Chinese president and the friends of Vladimir Putin. With reach and marketing skills like that, founding partners Ramon Fonseca and German-born Jurgen Mossack ought to be hired to recruit high-profile endorsements for the ‘Vote Leave’ campaign.

Comments