As Iraq fades from view so does our outrage at the crimes it provoked. Three monologues by Judith Thompson may cure our amnesia. Forgetting atrocities is an essential preliminary to repeating them. We meet a girl soldier (based on Lynndie England although not identified as her), who faces trial for brutalising prisoners at Abu Ghraib. At school she was a bullied bully, an opportunistic sadist who instigated attacks on others as a survival mechanism. Once she invited a girl with a false leg to a house-party where a gang removed the prosthetic limb, cut it to pieces, and jeeringly ordered the girl to crawl home.

At Abu Ghraib, this self-defence technique serves her again, and she strives to impress the male soldiers by devising pantomime humiliations. The famous pyramid of naked Iraqis she claims as her inspiration. But the cameras recorded only the mildest abuses. Trigger-happy guards would fire at prisoners’ feet and force them to eat excrement and perform homosexual couplings. It’s not clear how much fictional latitude the author has allowed herself here but the minor details ring true.

Languishing in military prison, the girl soldier becomes masochistically obsessed with online denunciations of her crimes. She sentimentalises Abu Ghraib, recalling it as a place of sexual adventure and joy, and she clings to a perverse fantasy that history will honour her as an American patriot.

The second monologue explores the back story of the weapons inspector David Kelly. The script presents him as a sophisticated, much-travelled bibliophile. His best friend in Baghdad owned an enormous bookshop, ‘the finest in the world’, Kelly says. The priceless stock should have been stored in a national library. There were ancient books written in blood, books so heavy three men couldn’t lift them, miniature books with pages as delicate as moths’ wings. The man had two children, the elder a teenager of unusual and precocious beauty.

A few days after the invasion, he telephoned Kelly in alarm. American soldiers kept staring at his 13-year-old girl, ‘the way a wolf looks at a rabbit’. Kelly assured him that the Americans were disciplined and honourable but the bookseller made plans to quit the city. A week later, the New York Times reported that he and his family had been killed in their cellar by an American patrol. The girl had been raped before being murdered. The bookshop was ashes.

Kelly heard of this crime on the day of his fateful appointment with Andrew Gilligan. No longer constrained by loyalty to the government, he revealed what he had known all along, that the weapons data was being manipulated. The bookseller’s story, if true, raises Kelly from a befuddled victim into a figure of Shakespearean proportions, a flawed hero who sought expiation in death. Robin Soans brings his fabulous array of resources to Kelly — warmth, vigorous intelligence and a penetrating humanity.

The final monologue, performed with terrific charm and humour by Imogen Smith, tells the story of the woman married to Iraq’s leading communist at the time when Saddam seized power. Her agonies in Baghdad’s torture-house — the Palace of the End — are almost unbearable to relate. Foolishly, I had dismissed this play as a feeble death spasm of the peace movement, but I was staggered by its power and scope. A production to rival Solzhenitsyn.

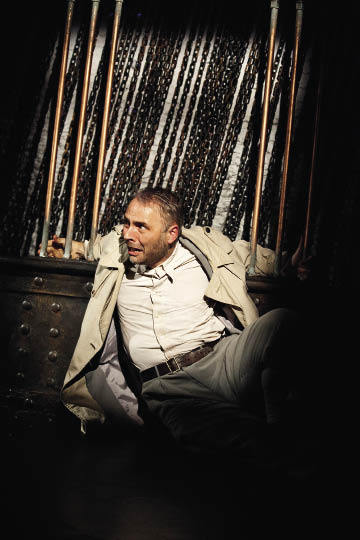

At the Trafalgar Studio there’s a solo performance by Mark Bonnar who was last seen at the National in Dido, Queen of Carthage. That production was underdone in all departments. The set looked like a squat, the costumes came from Primark, the wigs were fancy dress, the lighting was supplied by a becalmed wind farm and the ensemble playing had all the animation of a jellyfish in a sandpit. Few reviewers enjoyed Mark Bonnar’s dour, passionless, static Aeneas. But that wasn’t Bonnar’s fault. That’s just Aeneas. He’s a champion dull-wit. He’s Rome’s Mr Pooter. Faced with the same dilemma as Mark Antony, caught between arduous military duty and a life of dirty weekends with a silky north African temptress, he chooses military duty.

So it’s a pleasure to report that Mark Bonnar has leapt energetically from Aeneas’ louring penumbra to give a performance of great wit and delicacy. He tells the story of Novecento, a piano-prodigy born on a transatlantic liner in 1900, who dazzles generations of wealthy passengers and never leaves the ship. The script’s fairy-tale charm is marred by overwhimsicality. We’re told that, when Novecento plays at top speed, a cigarette held against the simmering strings will burst into flames. And when the retired liner is sent to be scuppered the pianist threatens to go down with her. Novecento is one of those whimsical baubles that win prizes, beguile fashionable opinion for a time and then vanish. But Mr Bonnar is on excellent form.

Comments