In the first book of his scientific-cum-philosophical poem ‘De rerum Natura’ — or ‘On the Nature of Things’ — Lucretius draws the reader’s attention to the power of invisible forces. The wild wind, he wrote,

whips the waves of the sea, capsizes huge ships, and sends the clouds scudding; sometimes it swoops and sweeps across the plains in tearing tornado, strewing them with great trees, and hammers the heights of the mountains with forest-spitting blasts.

It was a description I was well placed to appreciate as I read this whimsical, scholarly and original book while staying in a Georgian folly on a country estate in Kent. All around this mock gothic tower, in the words of Lucretius, ‘the frenzied fury of the wind’ shrieked, raged and menacingly murmured. Off the Welsh coast a ship sank and sailors drowned.

In the modern world the winds remain a formidable power. They still destroy and create, bring drought and rain, life and death. Alessandro Nova, an Italian art historian, has set himself the intriguing project of writing a history of how these invisible forces have been represented in art. How do you depict a current of air? Beyond that he sets himself another question: how do painters and sculptors show us anything that cannot be seen? Because, a moment’s reflection will reveal, art is full of images of things that cannot strictly speaking, be seen: thoughts, beliefs, even sounds.

The ancient Greeks regarded the winds, like rivers, as minor male gods. The Tower of the Winds, a building from the first or second century BC in the forum at Athens — part clock, part weather-gauge — is decorated with carvings of these blustery deities, one on each of its eight sides. Boreas, the cold and ferocious North Wind, is elderly and hirsute; Zephyr, the West Wind, bringing spring and summer rain, is a youth whose cloak is bulging with flowers and ears of wheat.

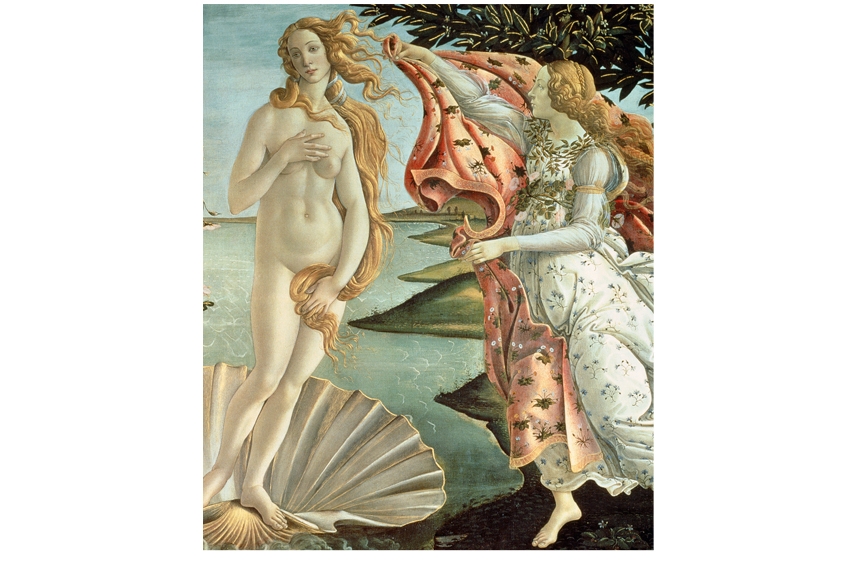

These personifications had a long life in European imagery. From them descend the puffing cherubs in the corners of old maps. Their most memorable appearances in the Renaissance, however, were in paintings by Botticelli. In ‘The Birth of Venus’, two fluttering figures with inflated cheeks waft the naked goddess to shore and to the right of Primavera a chilly-looking blue fellow clutches the nymph Flora (he is, according to Nova, impregnating her with his breath so that flowers stream out of her mouth).

There was another current of wind imagery: the Hebrew tradition in which a wind might be a manifestation not just of a minor, seasonal divinity, but of Almighty God. The prophet Elijah ascended Mount Horeb, where he fell asleep in a cave. In the morning he was struck by a wild, rock-cleaving storm, ‘but the Lord was not in the wind’. Nor was he in the earthquake and fire that followed, but then a light breeze arose, and Elijah, covering his face with his mantle, knew that he was in the presence of the Lord.

The sky and tempest as a manifestation of the divine go hand in hand in later European landscape painting with close observation of natural phenomena. Towards the end of his career, for example, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) produced drawings of cataclysmic tempests, in which cities are engulfed and tiny trees and figures blasted by mighty forces swirling in the sky.

It is not clear what subject, if any, he was depicting: the Biblical Flood, the Apocalypse, or some personal fantasy. But the formula he used to draw the twisting and spiral currents — like plaited hair or taut springs — is astonishingly close to a satellite photograph reproduced later in this book of El Niño creating a massive and menacing spiral weather system over the Pacific Ocean. That is decidedly one up to Leonardo, pioneer scientist.

The Book of the Wind charts an audacious course. Beginning in Classical Greece, Nova ends with contemporary artists such as Anish Kapoor, whose ‘Ascension’ is a miniature typhoon of vapour, shaped by enormous fans. It was to be seen — just — during the last Venice Biennale, curving skywards like a ghost beneath the dome of Palladio’s church of San Giorgio Maggiore.

On occasion Nova is blown off course. He spends a good deal of time on the storms and shipwrecks of 17th-century painting — a favourite subject of Dutch and Flemish masters — but waves and clouds are much easier to paint than currents of air, and scarcely invisible. Indeed, the question of when a work of art is actually representing wind and not just weather is an elusive one. But the pursuit of this art historical will-o’-the-wisp is enlightening, and accompanied by many beautiful illustrations.

Comments