For the impartial reader, this book is doubly disagreeable. An account of National Socialist short-wave radio broadcasts to the Arab world in the second world war, it prints pages of anti-Jewish propaganda as monotonous as it is vile. The author then shows no sympathy at all for Arab grievances, which makes the brew no more palatable.

Jeffrey Herf, who is a professor at the University of Maryland, contends that Nazi anti-Semitism broadcast across the Middle East from Berlin and Bari between 1939 and 1945 has borne fruit. Hatred of the Jews, discredited in mainstream politics in Europe by the Holocaust, has found ‘renewed life’ in the Arab world and Iran.

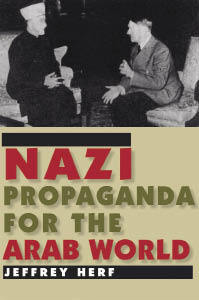

That the anti-Jewish statements of an Ahmadinejad or a bin Laden might owe something to European influence is an interesting question, but not one that Herf, knowing no Arabic or Persian, can answer. With the exception of the outright collaborators with Nazism in Berlin — the Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husseini and the Iraqi nationalist Rashid Ali al-Gailani — the Arabs and Iranians of this story might be on the moon. The book’s cover art, in which ‘Nazi’ and ‘Arab World’ are printed in blood-red type under a picture of Hitler with Haj Amin, is beneath the dignity of a university press.

The Arab world and Iran had deep grievances against the British empire and, in Iran’s case, Russia, which Germany exploited with sometimes brilliant success in the first world war. A quarter-century later, in the words of a report to the US War Department of August, 1942, ‘upwards of three-fourths of the Moslem world are in favour of the Axis’.

Though less systematic than Christians, the Arab countries and Iran have discriminated against Jews since at least the Prophet’s years in Medina. ‘And you will find the strongest in their hostility to the believers are the Jews and the polytheists’, says the Koran (5:82). (Berlin Radio often dropped the polytheists.) Jewish migration to Palestine, which provoked violent clashes with the Arab population as early as 1920, offered the Nazis a sort of common ground. As General Wilhelm Keitel of the Wehrmacht High Command put it with sinister understatement:

We are in a favourable position insofar as we need not promise the Arabs a merely ‘tolerable’ solution of the Jewish question.

In contrast, in the words of the US Office of War Information and in directions to Voice of America, ‘the subject of Zionist aspirations cannot be mentioned’ for fear that an Arab insurrection might threaten the chief Allied military assets in the Middle East: the Suez Canal, the Abadan refinery, the Persian Corridor supply route to Russia and lines of communication for the armies in North Africa.

So why, in the crisis years of 1941-42, with Iran racked by famine, Egypt under sullen occupation, the Muslim world in uproar over Palestine, Rommel at Tobruk and Paulus at Stalingrad, did the Germans make such a hash of the Near East and permit Britain to hang on to its ill-gotten oriental gains for another ten years? In other words, the question is not why Nazi propaganda in the Middle East was so successful, as Herf would have it, but why it was such a dismal failure.

The answer, as Herf well argues in his first chapter, was that the Nazis were bad racists. Their chaotic and incoherent racial theories provoked a diplomatic crisis with the Egyptians and Iranians even before the 1936 Olympics. Mein Kampf, which calls Egyptians ‘cripples’, was a minefield, while the Transfer Agreement of 1933 actually promoted Jewish migration to Palestine

As late as 1942, Franz von Papen, the Reich’s ambassador in Ankara, protested in fury at an article in Neues Volk describing Turks as of ‘alien’ (artfremde) race and proscribing mixed marriages. According to Hans Alexander Winkler, an orientalist attached to Rommel’s command in North Africa, Allied portrayal of German racial theories was ‘the most dangerous theme of enemy propaganda’.

Second, the Germans were hampered in their support for Arab nationalism by their Italian ally’s colonial ambitions in Libya. Pressed by Haj Amin for a public commitment to Arab independence at their meeting on 28 November, 1941, Hitler said he did not want to antagonise the Vichy French in Syria. As Fritz Grobba, German ambassador in Iraq till the collapse of the Gailani rising in 1941, complained: ‘Hitler and Ribbentrop showed a total lack of interest in Arab aspirations’. The Germans responded too late to help Gailani in Iraq and all but ignored Iran except to send a Funkkommando with a few gold coins and some dynamite, which passed the war in Arcadian conditions among the Qashqai tribesmen.

Finally, the Arabs could see which way the strategic wind was blowing. In July, 1942, and Rommel within 60 miles of Alexandria, Radio Berlin at last broadcast the joint German-Italian declaration to ‘guarantee Egypt’s independence and sovereignty’. On 7 July, a transmitter called the Voice of Free Arabism urged the Arabs to ‘kill the Jews before they kill you’. There was no response and the British reported little sabotage.

With Rommel’s defeat at Alamein in October and the German surrender at Stalingrad in February, 1943, Berlin Radio altered its tone, raved at the United States and its ‘Jewish President’ Roosevelt and threatened an apocalypse of Jewish mastery in the Middle East. Orientalists working for the SS at Tuebingen attempted to portray Hitler as the Jesus of shia eschatology, who slays the (Jewish) Anti-Christ and ushers in the end of time. Haj Amin’s call for general insurrection on 1 March, 1944 fell on deaf ears. Herf’s claim that Haj Amin’s ‘ideological achievement bears some comparison to Hitler’s’ is utterly daft.

James Buchan’s latest novel is The Gate of Air (MacLehose Press).

Comments