There was no reason for Edward Drummond to believe this January day was going to be different to any other Whitehall working day. Having completed his civil service chores and visited the bank, he set off back to Downing Street where, as the prime minister’s private secretary, he had an apartment. He was passing a Charing Cross coffee shop when, without any warning, he felt a searing blow to his back and, according to a witness, his jacket burst into flames.

The bang drew the attention of a quick-witted police officer, who dashed across the road as a man prepared to shoot at Mr Drummond again. But even with the assistance of passers-by, the officer struggled to disarm the shooter. He violently resisted and discharged a second shot, though this time without causing injury to anyone. Eventually overpowered, the shooter — a man named Daniel McNaughton — was arrested and detained in police custody.

Drummond’s initial prognosis seemed hopeful. But then his condition worsened and within five days of the shooting, he was dead. McNaughton’s crime had become a capital offence.

Despite his resistance to police at the scene, McNaughton was surprisingly co-operative under questioning. But it wasn’t only his willingness to admit to the shooting that surprised the police. It became apparent that his intended target had been the prime minister, Sir Robert Peel.

McNaughton was a Scottish craftsman who, following a brief acting career, set up his own woodturning workshop in Glasgow in 1835. An industrious and frugal man, McNaughton ran his workshop for five years and was able to save a considerable sum of money, teaching himself French and attending lectures on anatomy in his spare time.

Under police questioning, he appeared unconstrained in sharing the extent to which he felt he had been terrorised by the ruling elite. The shooting, it emerged, was the denouement of a conspiratorial tale that on first hearing appeared fantastical. Known to have radical political views, McNaughton had complained to both the Glasgow commissioner of police and an MP that he was being followed by Tory spies.

A series of prosecution witnesses, including McNaughton’s landlady and his anatomy teacher, testified that they had observed no signs of mental derangement. But to the eight eminent physicians and surgeons called by the defence it was obvious that McNaughton had accepted unquestioningly a fiction invented by his psychotic mind. Their evidence proved compelling. The jury was directed to reach a verdict and, without even retiring, the foreman announced on 4 March 1843 that they found the prisoner not guilty on the ground of insanity.

The public was aghast: convinced that criminals and violent madmen would be encouraged to terrible deeds by such leniency. To the press too, the verdict was an outrage. This was a carefully plotted and fully confessed crime — yet McNaughton was being found not guilty. Queen Victoria, reminded of the attempt on her life three years earlier by a man also deemed by the courts to be insane, was moved to intervene. In correspondence with Sir Robert Peel, she asked Parliament for a tighter definition of insanity.

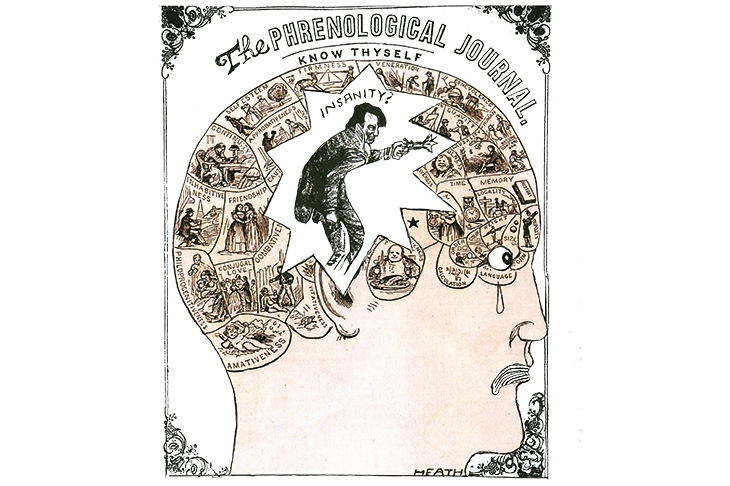

In response, the rattled criminal justice system laid the foundations for an enduring approach to understanding the mental origins of criminal behaviour. McNaughton’s name has since become part of legal history — the McNaughton Rule declares that the defence of insanity requires clear proof that the accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from a disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of his actions. Reason and disease were placed centre stage in the law’s assessment of the criminal mind.

The medical model relies on the process of diagnosis to identify underlying disease, which is then treated by either reversing or removing it. I have practised forensic psychiatry for 21 years and acted as an expert witness in innumerable cases. And the more I have examined the criminal manifestations of the human mind, the more I have seen the limitations of medical diagnosis. To me, reducing types of consciousness to broad brush diagnostic labels obscures rather than reveals the fascinating patterns created by a constant swirl of interacting thoughts, perceptions, feelings and impulses.

Today’s system of classification of mental illness can be traced to the attempts to organise the confused psychiatric nomenclature that prevailed at the time of McNaughton’s trial. An influential broad dichotomy of insanity was introduced by the German psychiatric empiricist Emil Kraepelin in the 1890s. He proposed two types: episodic manic-depressive psychosis (later updated to bipolar disorder); and a progressively deteriorating psychosis which he called dementia praecox (‘a precocious madness’); a label that was to fall out of fashion in favour of schizophrenia. Repeated subdivisions over the following 120 years have produced more than 500 diagnoses within today’s iteration of the controversial Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Despite these refinements, hair-splitting debates over a patient’s diagnosis remain a regular feature of psychiatric case-conferences.

As a forensic psychiatrist, I have also become accustomed to a much more testing and combative arena. Not only are criminal courts adversarial by design, but the questions are far more challenging since lawyers often do not accept the basic assumptions that psychiatry takes for granted. My opinion that a homicide is attributable to the killer’s diagnosable condition is not enough for their lawyers to present a defence of diminished responsibility to a murder charge. The court needs to know how the condition affected his mind so as to cause him to kill.

We attribute the social and psychological problems of modern society to the fact that society requires people to live under conditions radically different from those under which the human race evolved and to behave in ways that conflict with the patterns of behaviour that the human race developed while living under the earlier conditions.

These words were penned by a former professor of mathematics who was also the author of a campaign of indiscriminate homicidally motivated violence stretching over 17 years. Driven by hostility towards modernity, Theodore ‘Ted’ Kaczynski dispatched > incendiary devices across the United States killing three people and injuring another 23.

Known as the Unabomber, due to his targeting of universities and airlines, Kaczynski had been a brilliant mathematician. With an IQ of 170, he became an undergraduate at Harvard University aged just 16, and went on to earn a Master’s and PhD in mathematics at the University of Michigan. He joined U.C. Berkeley in 1967, but then — without explanation — abruptly resigned after two years. Frustrated by the rapidly changing world, Kaczynski had shunned academic life and moved to Montana, where he began building a cabin in the woods. He lived there as a hermit, completely cut off from the modernising world.

It was in this hideaway that, between 1978 and 1995, Ted Kaczynski manufactured 16 increasingly sophisticated bombs. Eventually, he offered to halt his revolutionary actions if his manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future, was published.

The 35,000-word manifesto appeared in the Washington Post and the New York Times in September 1995. After reading it David Kaczynski noticed content and stylistic similarities with his older brother’s letters from the 1970s and went to the FBI. In the spring of 1996 Theodore Kaczynski was arrested at his cabin.

During the subsequent trial, a court-appointed psychiatrist’s assessment was that Kaczynski suffered from schizophrenia. Had present-day diagnostic approaches been in use in the 1800s, Daniel McNaughton would also have received the same diagnosis.

The controversy in both the McNaughton and Kaczynski cases centred on the apparent lucidity of the men in spite of claims by the experts of insanity. How could a diagnosis of schizophrenia be squared with Kaczynski’s capacity to execute meticulously planned crimes, to avoid detection for so long, and to compose a novella-length manifesto? While bizarre and dangerous in parts, Industrial Society and Its Future contained ideas to which large sections of society would subscribe. After its publication, professor James Q. Wilson of University of California wrote in the New Yorker that the manifesto was ‘a carefully reasoned, artfully written paper’ and that ‘if it is the work of a madman, then the writings of many political philosophers — Jean Jacques Rousseau, Tom Paine, Karl Marx — are scarcely more sane’. Is it his willingness to act on these beliefs — and to cause harm to members of the public — that separates Kaczynski from Rosseau, Paine and Marx? What has become increasingly clear to me is that diagnosis does not illuminate the causes of behaviour. I have been involved in too many trials in which the central issue has been on whether the criteria for specific diagnosis were met.

In the case of Ted Kaczynski, the matter was never resolved. The trial was brought to an abrupt halt when, faced with the prospect of his legal team humiliatingly portraying his philosophy as the ravings of a madman (against his express wishes), Kaczynski changed his plea to guilty of murder.

Does it help our understanding of their criminal behaviour to know whether or not Kaczynski or McNaughton suffered from schizophrenia? Here we return to the problems with the disease model in psychiatry. When I ask trainee psychiatrists to define schizophrenia, they talk about psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. If I ask them to define a physical health condition such as asthma they talk about an inflammatory airway disease resulting in bronchospasm: they may include symptoms (wheezing and shortness of breath) in their answers, but do not rely on symptoms alone. Pondering whether the diagnosis is schizophrenia or not, which we spend so much time doing in clinics and court, takes us down an explanatory blind alley.

A different and newer type of expertise seems to offer a better way of explaining the criminal mind. With the technology to remotely visualise the activity of the brain’s hardwiring, neuroscientific evidence has been introduced to criminal courts. These quantitative researchers — measuring blood-flow as a proxy for nerve cell activity — crunch group-level data to identify commonalities within groups. Yet as a forensic psychiatrist I strive to trace the source of an individual’s flawed choices and behaviour. Mine is an exploration of the individual’s uniqueness.

Neurobiological studies have undoubtedly improved our understanding of the origins of violence by highlighting possible brain mechanisms. But its advocates overlook the fundamental limitation of neurobiology as an explanation of behaviour. The goal of this scientific field is to produce an objective depiction; one to match the inflamed airways explanation of asthma. The difference is that brain-based representations describe, but they don’t explain. In itself, a neurobiological narrative will never be sufficient for understanding mental disorder or criminal behaviour. Human behaviour cannot be fully explained without including the subjective perspective. In explaining violence, the physiology of the brain has to be contextualised by psychological abstractions of the mind such as impulses, urges, motives, and inhibitions. Understanding these subjective phenomena is central to eliciting the origins of violence.

Comments