In 1973, everyone loved David Bowie. Album buyers had put Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and Hunky Dory high in the charts, while singles buyers had bought similar success for ‘Drive In Saturday’, ‘Life on Mars’ and ‘Sorrow’. Then right in the middle of this, he released ‘The Laughing Gnome’. In truth, he probably didn’t. It was a twee little novelty song recorded six years earlier, featuring Bowie duetting with the eponymous gnome.

Nobody could believe that Bowie had recorded it – less still that he’d written it – but the more you know about him, the less surprising it seems. In fact, ‘The Laughing Gnome’ says more about David Bowie than anything else he did.

It was early evidence that he would do anything to be famous. He was a true genius but less for his musical talent and more for his cold-eyed obsession with fame and for spotting the ‘influences’ he’d need to achieve it. On ‘The Laughing Gnome’, that influence was Anthony Newley and, had it brought Bowie the fame he craved, he’d probably have been happy for the rest of his days as a family entertainer, hosting game shows on ITV. But ‘The Laughing Gnome’ flopped so a couple of years later, he tried again with another novelty song.

This one didn’t flop. ‘Space Oddity’ was a complex, multi-layered production with sonic intricacies that did much to conceal its childish narrative and puerile pun of a title. Bowie’s first hit – in its style, structure and use of minor chords – bore more than a passing resemblance to The Bee Gees’s first hit ‘New York Mining Disaster 1941’. Nonetheless, by invoking the moon landings and the success of 2001: A Space Odyssey, ‘Space Oddity’ reached number five in the charts. Yet its creator’s one-hit career seemed as doomed as Major Tom’s.

Further years of failure followed but with that extra ounce of ambition that wasn’t quite sane, David Bowie did not give up. Instead he looked for the next person whose work he could ‘adapt’ and his covetous gaze fell upon Marc Bolan. He’d seen how Bolan had gone from fop-haired folky to glam-rock icon and decided to copy that journey.

Bowie’s destination was that famous episode of Top of the Pops when Bowie – fully made up as the androgynous Ziggy Stardust – slung his arm around Mick Ronson to sing the chorus of ‘Starman’. Determined that no one would forget this carefully contrived performance, he’d deliberately written that chorus to give ‘star-man’ exactly the same octave leap as ‘some-where’ in ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’. By combining the edgy and outré with the sweet and familiar, David Bowie made himself a star.

From that moment, his life would be grimly devoted to making sure he remained one. To do this, he moved on from Bolan and began to embezzle the work of other artists, casting each one aside when it was time to re-invent himself and turn his vampiric attention to somebody else. The examples are countless, obvious and – quite literally – on record.

Once glam lost its gleam, he noticed that Bryan Ferry had released These Foolish Things, an album of casually crooned cover versions. Almost immediately, Bowie did the same thing with Pin Ups. Only without Ferry’s insouciant ability to croon.

A couple of years later, Mick Jagger told Bowie that he was commissioning Belgian artist Guy Paellart to create the cover for The Stones’s new album It’s Only Rock’n’Roll. Big mistake. Bowie went straight to Paellart and convinced him to create the cover of Diamond Dogs instead. To add musical insult to artistic injury, Diamond Dogs – particularly its standout track ‘Rebel Rebel’ – sounds uncannily like The Rolling Stones.

With Young Americans, Bowie – re-invented again as the Thin White Duke, made a thin white joke when shamelessly describing the album as ‘The definitive plastic soul record – the squashed remains of ethnic music’.

Never mind. Onwards and upwards. For his next incarnation, Bowie ‘absorbed’ the brilliance of Brian Eno. Together they produced Low, side two of which is almost entirely instrumental. It’s the kind of ambient, electronic music which Eno pioneered but it’s all credited to David Bowie. It’s only fair to point out that Bowie himself was a huge influence on other artists, notably Gary Numan. Though when Numan comprehensively outsold Bowie in 1979, the old rogue decided to co-opt the sound of his putative protégé. You only have to listen to Scary Monsters & Super Creeps to hear Bowie’s debt to Gary Numan.

As the 1980s dawned, Bowie saw how Nile Rodgers had rejuvenated Diana Ross’s moribund career with ‘I’m Coming Out’ and ‘Upside Down’. So to the surprise of absolutely no-one, Rodgers was recruited to produce Bowie’s next album Let’s Dance. Pop-y and mass market, it was far and away his greatest commercial success. Possibly because it sounded just like a Chic album, though one on which Bowie’s vocals shone some serious moonlight.

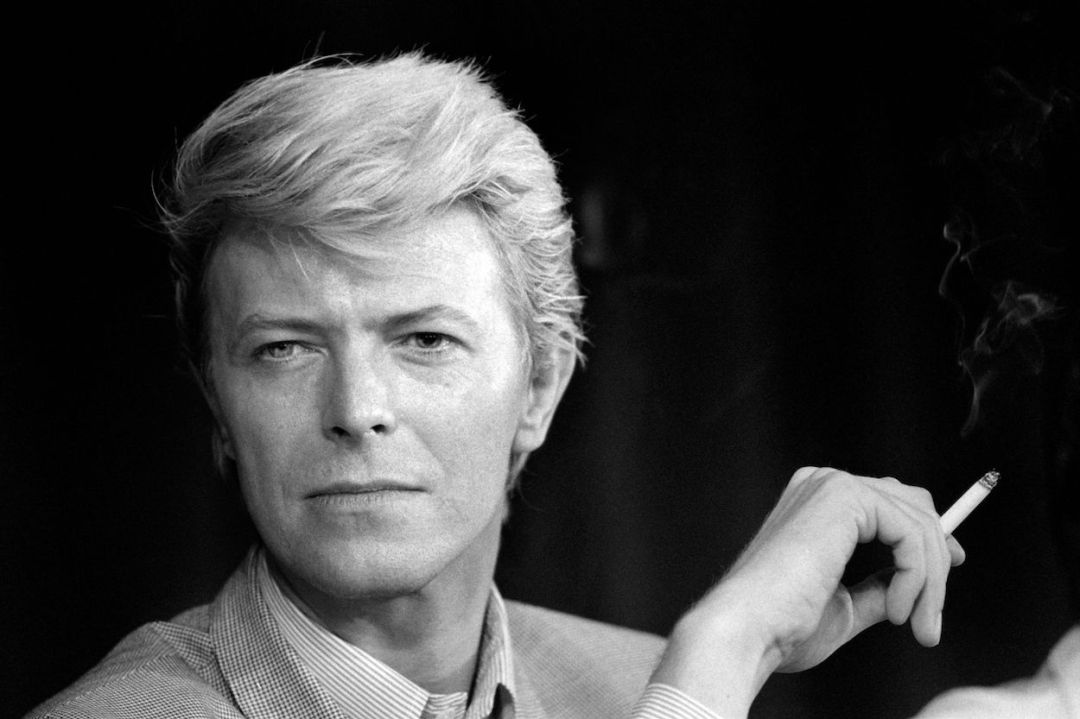

David Bowie’s greatest attribute was that seemingly effortless aura of cool. Though given his calculating approach to everything, I doubt very much whether it was effortless. But it was this that allowed him to be viewed as a great innovator when he was nothing of the sort. He was a cunning and ruthless grafter who helped himself to the ideas of others and incorporated them into an ever-changing persona.

By routinely latching on to the next big thing, he was always slightly behind the times rather than ahead of them, and his truest fans acknowledge this. They understand that this is what made him so fascinating. It’s what made him David Bowie. I count myself among those fans. I’ve been buying his records since I was at school and I still love every single one of them. So in the end, does it really matter whether David Bowie stole most of his best ideas?

Comments