Picasso collected papers. Not just sheets of the exotic handmade stuff — though he admitted being seduced by them — but any scrap that could inspire, support or become part of an image. He jettisoned muses like there were endless tomorrows but clung on to Métro tickets, postcards, restaurant bills, bottle labels. When the thrill of a muse was gone her creative possibilities were exhausted, but you never knew, with synthetic cubism, when that old Métro ticket might come in handy.

In a garret he would have had a hoarding problem. ‘Picasso throws nothing away,’ reported one lover. There was no filing system: a photograph in the exhibition shows a bulldog-clipped bunch of correspondence hanging from the ceiling at rue des Grands-Augustins. After his heirs were left to pick over the hoard, they dumped it on the Musée national Picasso-Paris, the principal lender to this Picasso and Paper exhibition at the Royal Academy; given the run of the Academy’s main galleries, the show barely scratches the collection’s surface.

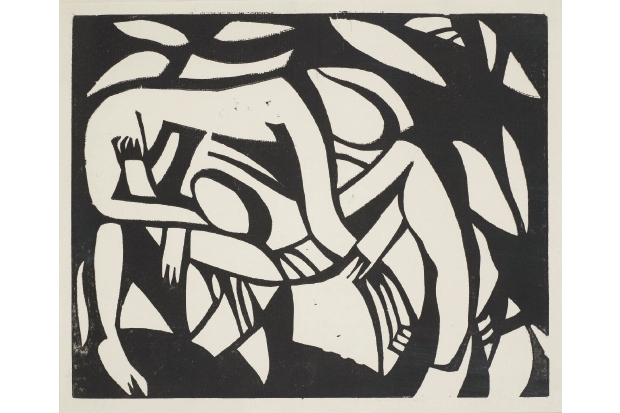

The old erotomaniac was 86 when he drew ‘The Kiss’, a calligraphic close-up of a tongue sandwich

The result is a delicious taster menu consisting mainly of hors d’oeuvres and amuse-gueules — if you had a bellyful of plats principaux in Tate Modern’s Picasso 1932, then this one’s for you. A few key paintings or sculptures provide focal points around which to group related pieces of paper, starting in the blue period with ‘La Vie’ (1903), on its first visit to the UK from Cleveland. The 1909 bronze ‘Head of a Woman (Fernande)’ marks the advent of cubism and the 1932 bronze ‘Head of a Woman (Marie-Thérèse Walter)’ — apparently moulded from baguettes by a priapic Arcimboldo — the onset of surrealism; the absent ‘Demoiselles d’Avignon’ are represented by a bevy of Africanised nudes and the work of ‘Guernica’ is done by a cortège of knackered horses and weeping women.

There are drawings on every grade of paper from rag to newsprint, in every medium: pencil, charcoal, pastel, crayon, gouache, ink. The line drawings are pristine, the brush drawings dazzling: a thin brush is wielded with the finesse of an ancient Greek vase-painter in ‘Boy with Cattle, Gósol’ (1906), a fat one with the splashy élan of a rustic potter in ‘Bullfighting Scene, Vallauris’ (1959). And there are the prints that poured out of Picasso: etchings, lithographs, linocuts and experimental variations of his own invention. ‘He looked, he listened, he did the opposite of what he had learnt —’ said one lithographer, ‘and it worked.’ Paper is cut, torn, folded, pasted or fixed with pins to papiers collés. The largest work is the 4.8 metre ‘Femmes à leur Toilette’ (1937) collaged from wallpapers; the smallest are painted cut-outs from 1914 of random objects — glasses, light bulbs, a cuttlefish — and torn death’s heads from 1943 with cigarette burns for eye sockets.

Picasso couldn’t remember a time when he couldn’t draw: a family myth was that his first word had been ‘lapiz’, ‘pencil’. He made a perfect cut-out of a pigeon when he was around nine, an accomplished academic study of an antique cast when he was 12 or 13. ‘One should not learn to draw,’ he maintained later; one would only have to unlearn. His touch didn’t change but his subject matter of melancholy paupers and saltimbanques did, after sex reared its polymorphous head with Marie-Thérèse Walter. Martin Amis and Craig Raine had a laddish theory that it was a flaw of female design that breasts and buttocks were on different sides; if so, it was a mistake the multiple perspectives of cubism allowed Picasso to correct. In his fifties his inner Minotaur was unleashed — ravaging an ivory-skinned Dora Maar against a flame-red sky in a coloured pencil drawing of 1936 — and the beast was never put out to pasture. Sex dominated his imagery into his dotage: the old erotomaniac was 86 when he drew ‘The Kiss’ (1967), a calligraphic close-up of a tongue sandwich.

Picasso was an incorrigible show-off. In Henri-Georges Clouzot’s film Le Mystère Picasso the septuagenarian artist, bare-chested like a nut-brown Putin, acts the magician with a felt-tip pen, conjuring a laughing faun out of a chicken out of a fish out of a bunch of flowers. Can you see what it is yet? What makes this exhibition so very special is that it catches Picasso when he’s not showing off.

Comments