George Osborne has declared victory over Ed Balls, the IMF and all the others who warned that his austerity measures would throw Britain back into recession. But his triumphalism obscures a huge failure: his inability to contain the national debt. While the UK economy has been growing strongly (it is currently the fastest-growing of any developed country) the public finances have taken a dramatic and sudden turn for the worse. It emerged this week that, between April and September, the Chancellor borrowed £58 billion — £5.4 billion more than during the same period last year.

Osborne’s original plan to eliminate the structural deficit by the election has been off course for a long time, but it is now going backwards. This is embarrassing for a Chancellor who is about to fight the next election on financial competence. Yes, the number of jobs is soaring, but only because salaries are so miserable. The nature of the jobs created — chiefly, those at the bottom of the pay scale — explains why tax revenue is not being generated as fast as he expected. Even now, the economic recovery he once forecast is almost two years behind his original plan.

Osborne has now given himself eight years to cut state spending — by just 3.9 per cent. This is not the work of an Iron Chancellor, more like a child peeling off a plaster slowly so as to minimise the pain. It is funny to think that Labour’s Denis Healey cut state spending by 3.9 per cent in just one year (1976) when the IMF told him to.

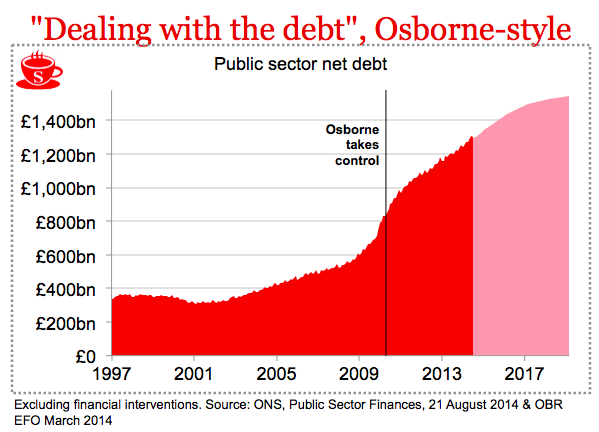

Osborne’s slow-motion austerity has a price: the national debt, which stood at £975 billion when he took office, is £1,450 billion now, and rising fast.

As the election approaches and the parties fall over themselves to offer the usual bribes, the Chancellor’s discipline is weakening further. His pledge not to seek any savings from the Department of Health budget is extraordinary, given the pressure this will place on other departments. He has also committed the Tories to a potentially ruinous ‘triple lock’ guarantee on state pensions. To make such promises in the heat of an election campaign would be understandable, if regrettable. To make them now borders on reckless.

Osborne is not an austerity chancellor. He is no 1940s housewife eking out the ration stamps. He is more like a footballer’s wife who feels so smug after ‘saving’ herself a few hundred pounds buying clothes in a sale that she goes out and blows most of her illusory ‘savings’ on a slap-up dinner. Where does he think Britain will find the money for his pet project, the entirely unnecessary High Speed 2? And why, in the midst of a supposed austerity drive, does he boast about the amount spent on foreign aid? Once you define a success purely in terms of money spent, you guarantee waste, as that is the easiest way for officials to reach the target.

If the Conservatives want to go into the next election as the party of financial competence — and they are sunk if they do not — the Chancellor is going to have to convince us that he is serious about reducing spending. At the moment he is using verbal tricks — saying he will ‘deal with the debt’ — by which he means (at present) increasing the debt at the rate of £3,000 a second. Every day of delay means permanently higher national debt, which in turn means saddling the next generation with higher taxes.

There is one benign explanation for the dismal tax receipts. The coalition has (at the behest of the Liberal Democrats) raised the personal allowance for income tax. This may explain why, over the last four years, the number of working-age people in work has risen by 5 per cent, but the number paying income tax is down by 7 per cent. New jobs are being created mainly in places where salaries tend to be lower, like the East Midlands and the north-east of England.

So the Chancellor does have some excuse for taxes not being as strong as he had hoped: he’s a tax-cutter, and his fiscal reforms are working. The hope is that the deficit problem is transitory, and will vanish when the workers move to higher-paying jobs and start to pay tax. After all, Osborne’s corporation tax cuts cost money at first. Now, corporation tax revenues are soaring, up 5 per cent this year so far.

With memories of the great recession fading — and the economy apparently back on its feet — it is going to be harder to convince the public of the need for less and cheaper government. But it will be harder still for a Chancellor who has fought the election promising tax cuts, but barely mentioning spending cuts. If Conservatives are to gain the upper hand in the inevitable clashes with the unions which will result from any attempt to shrink the state, it is vital that they win a proper mandate to continue to try to eliminate the deficit.

Comments