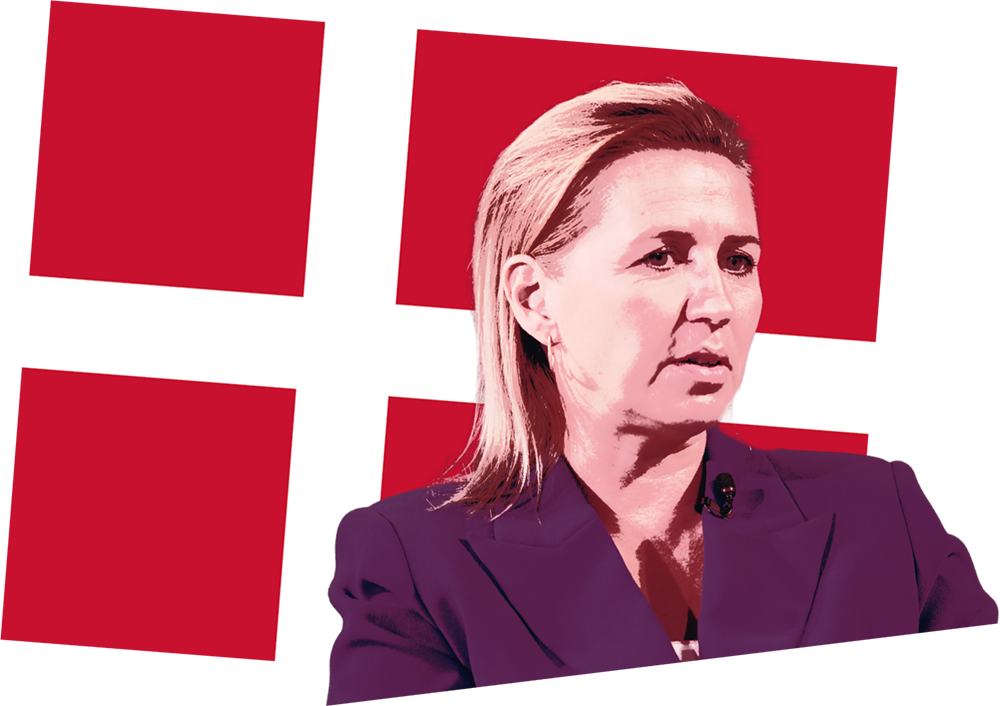

Something unusual is happening in Denmark – and other countries across Europe, including Britain, ought to pay attention. This spring, Denmark’s Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, stood before a group of university students and made a striking statement: ‘We will need a form of rearmament that is just as important [as the military one]. That is the spiritual one.’

Few expected such words from the leader of the Social Democrats, a party which spent much of the 20th century reducing the Church of Denmark’s influence in public life. Yet this was no passing remark. Just days earlier, Frederiksen had announced a major military build-up: increased conscription, a sharp rise in defence spending and intensified strategic readiness. Like the rest of Europe and Nato, Denmark is preparing for a more dangerous world.

But there’s a deeper problem, one that Frederiksen – unusually for a western leader – has dared to identify. Many young Danes are unwilling to fight. Some openly admit they wouldn’t die for Denmark – not for democracy, not for the flag, and certainly not for a modern welfare state that promises everything but inspires nothing.

This is not just Denmark’s crisis. It affects all post-Christian societies and raises a question that Britain, too, must confront. What binds a people together when the systems they trusted start to falter?

Denmark is among the most secular nations on Earth. Though the Church still exists by law, it plays little role in the daily lives of most citizens. Religion is viewed as a private matter. For generations, the state has quietly absorbed the Church’s traditional functions: care for the poor, moral formation, rites of passage, community. And yet the country’s Prime Minister is now calling on the Church to return. In an interview with the Christian newspaper Kristeligt Dagblad, she went even further, urging the Church of Denmark to step up not merely as a cultural institution, but as a vital part of national life.

‘I believe that people will increasingly seek the Church,’ she said, ‘because it offers natural fellowship and national grounding… The church room has helped people through many crises. I believe the Church will find that these times call for such a space.’

Then came a sentence that would have been unthinkable from a Danish Social Democratic Prime Minister just a decade ago: ‘If I were the Church, I would be thinking right now: how can we be both a spiritual and physical framework for what Danes are going through?’

This is not religious romanticism. It is political realism. It is the recognition that rights, services and social protections cannot sustain a society on their own. People are not willing to suffer for tax models. They do not risk their lives for procedural democracy. But they will fight for what they hold sacred.

Denmark is discovering what many nations in the West are about to learn: that a system built on comfort, entitlement and personal freedom leaves nothing to defend when hardship occurs. And hardship – in the form of war, threat and sacrifice – is returning to the European Continent.

Britain is in a similar situation. Military recruitment is declining. Political leaders speak of new global threats and of boosting defence spending, but say nothing of belief, meaning or moral courage. No one seems to be asking the fundamental question: do we have anything left that people would die to protect? That is the real crisis.

What is becoming clear in Denmark is the limit of secular governance. Rights and freedoms, as noble as they are, do not exist in a vacuum. They are the fruit of a deeper moral vision, one rooted in transcendence, in religion, in a shared understanding of truth and goodness. Cut off from those roots, the tree will not stand. And when sacrifice is required, the will to make it will vanish.

This is why Frederiksen’s words matter. They are not necessarily a return to personal faith, but they are an admission that faith itself is necessary. That no civilisation can survive, let alone defend itself, without something sacred at its foundation.

Britain still retains symbols of faith – cathedrals, bishops, coronation liturgies – but without conviction, those symbols will become museum pieces: objects of nostalgia, not sources of strength. In the end, the question facing every western democracy is not how to govern, but why it exists.

The fact that a call for ‘spiritual rearmament’ has come from the Prime Minister of Denmark suggests that the crisis of meaning is finally reaching the most rational, bureaucratic and post-religious corners of European politics. Even those who replaced the Church with the welfare state are beginning to feel the ground shifting beneath them.

Comments