Jean Rhys, who died at the age of 88 in 1979, lived to be forgotten and rediscovered. Like many readers, I first came across her through her novel Wide Sargasso Sea, which imagines the pre-history of Jane Eyre’s ‘madwoman in the attic’, the Creole heiress married off to Mr Rochester and then incarcerated by him at Thornfield Hall. When it came out to great acclaim in 1966, it marked the rebirth of a writer who hadn’t published a book for more than a quarter of a century and who had even been presumed dead.

Born Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams in Dominica in 1890, Rhys drew on her own background as a displaced Creole – the word indicates a white person from the Caribbean – to give splintered subjectivity to the character so brutally ‘othered’ by Charlotte Brontë. Her childhood in the tropics left its mark, though she was sent to school in England in her late teens and never went back except for one short visit. As the daughter of a Welsh doctor and a mother whose down-at-heel family had once been wealthy slave owners, she was caught between her colonial parents and the Afro-Caribbean servants whose culture and language she imbibed. (There’s a recording of the elderly Rhys singing a Kwéyòl song in the archive.) Issues of identity and alienation, power and exploitation echo through her entire oeuvre. She never felt at home. At 14, she had been sexually abused by a family friend, in whose whispered fantasies she was his slave, stripped and whipped.

Extraordinary though Wide Sargasso Sea is, it was when I read Rhys’s four earlier novels, set in Paris and London, two cities where she lived, that I was truly blown away. These works, especially her masterpiece Good Morning, Midnight (1939), reveal her as one of the 20th century’s greatest modernist writers, but her acceptance into the canon has been comparatively slow. Many of her writings remain unpublished, and available editions of her novels lack full-scale academic apparatus. Scholarly recognition for women modernists has in general come later than for the men.

Aged 14, Rhys was sexually abused by a family friend, in whose fantasies she was his slave, stripped and whipped

Rhys’s literary reception has not always been helped by a focus on the troubled life and personality of the author. Following her rediscovery – which was primarily brought about through the patient efforts of the editor Francis Wyndham – she became something of a cult figure in literary London. Colourful anecdotes abounded of her eccentricity, her dipsomania and her foul-mouthed rages. In 1983, her one-time amanuensis David Plante published a character sketch in which he described with relish how he once had to yank the inebriated old lady out of the loo after her bottom got stuck in the porcelain well (actually, it was his fault – he had failed to replace the seat after using the facilities himself).

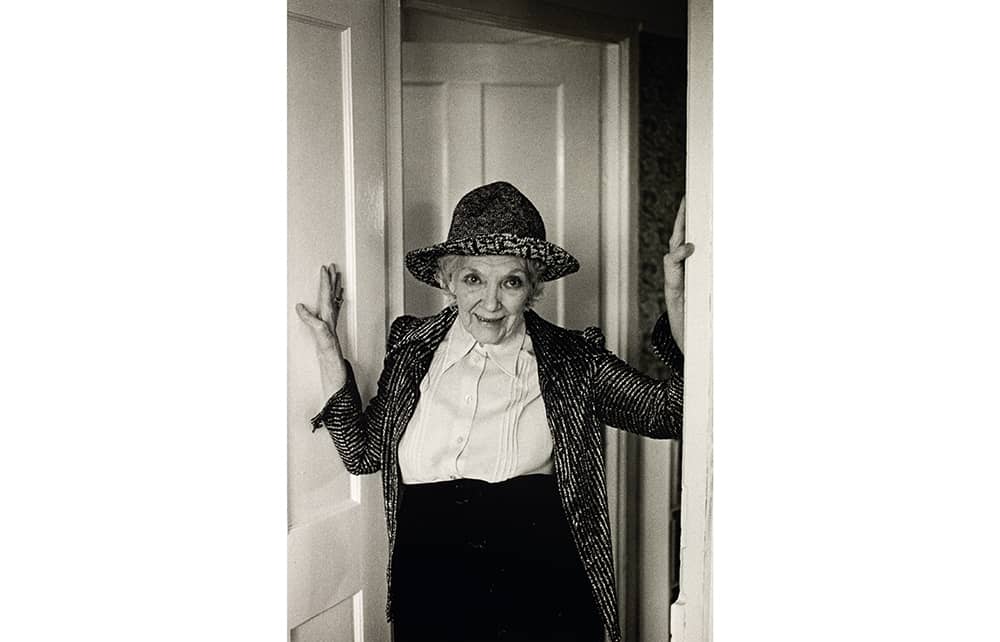

Such gossip made the elderly Rhys – over-made-up, wig askew – seem like one of Diane Arbus’s ‘Freaks’. Her writing was admired, but as if it was itself a freak of nature. In 1985, a pioneering first biography by Carole Angier diagnosed Rhys with ‘personality disorder’, concluding: ‘She should only have been a cripple, only a drunkard. But she was not. That was the mystery.’ One cannot imagine a biographer saying the same of a male writer like Rhys’s contemporary Ernest Hemingway (whom she met in Paris in the 1920s). His drinking and relationship problems have not tended to result in critics pathologising his work.

Central to Rhys’s fiction is what became known as the ‘Rhys woman’: a female protagonist defined by her victimhood at the hands of men, usually assumed to be a carbon copy of the author, as if her work were artless memoir. According to Angier, she ‘could only write instinctively, unconsciously’. A more novelistic treatment, The Blue Hour by Lilian Pizzichini (2010), drew on Angier’s research and led to lurid headlines such as ‘Prostitution, alcoholism and the madwoman in the attic’.

The superb achievement of Miranda Seymour’s painstaking and compassionate new biography is to dispel forever the idea that Rhys was simply a naive chronicler of her own experiences. Certainly, she used autobiographical material in her fiction. But Seymour is wiser than her predecessors both to the sophistication of Rhys’s art and to the fact that a literary text should never be trusted on its own as documentary evidence of actual events. The assumption, for example, that the young Rhys worked as a prostitute is shown to derive from an over-literal reading of her 1934 novel Voyage in the Dark rather than from external evidence.

That book draws on her experiences before the first world war as a chorus girl in a travelling troupe, for which she had bravely auditioned after a brief spell at Rada came to an end, due to prejudice at her colonial accent. Its central relationship is based on her first love affair – with a wealthy banker, who paid for her abortion but did not marry her. Unlike the novel’s heroine, Rhys took on work as a movie extra and artist’s model rather than as a streetwalker in the traumatic aftermath of their break-up. Plunging into the life of bohemian Chelsea and the Crabtree Club in Soho, she began to write seriously for the first time, though she had written poetry from childhood. After the Armistice, she moved to Paris with her first husband, Jean Lenglet, a Dutch novelist, fraudster and spy, who lived life on the edge and whom she married despite being warned against it (he later became a hero of the Dutch Resistance).

In common with other female bohemians of her day – including fellow colonials Stella Bowen and Katherine Mansfield – Rhys was open to a life that affronted bourgeois norms. Virginia Woolf famously opined, from a position of entitlement, that a woman needed both money and a room of her own to write fiction. The vagabond Rhys – who combined a taste for extreme risk-taking with inner insecurity, even timidity – had neither.

Her fictional world is that of Prufrock’s ‘restless nights in one-night cheap hotels’, where women sleepwalk through the alien landscape of the modern city. Like her heroines, she was always dependent for her keep on lovers (including the novelist Ford Madox Ford), unreliable husbands (two of whom, out of the three, spent time in jail) and other patrons (a French family paid for her daughter to be housed in an orphanage). In the long period of silence after Good Morning, Midnight – which saw Rhys drinking heavily and at one point briefly incarcerated in the medical wing of Holloway prison – she landed up living in abject poverty with her third husband in what was little more than a shack in Devon.

Seymour suggests that it was less that drink stopped Rhys writing that the loss of her writing identity made her more and more dependent on drink. Her publisher dropped her after Good Morning, Midnight, as the gloom and sordidness of her vision was seen as a turn-off to readers. Her second husband, Leslie Tilden-Smith, an editor himself, warned her that her books weren’t marketable and that people would make the mistake of identifying her too closely with her heroines, but she was uncompromising.

As Seymour emphasises, the signal difference between Rhys and her female protagonists is that none of the latter are capable of writing books. It was on the page, as a consciously literary writer, that Rhys had agency. The title of Good Morning, Midnight is taken from a poem by Emily Dickinson; its final words are a sardonic quotation from Ulysses. Influences and allusions abound in her oeuvre, from Maupassant to George Moore, from Colette to Céline. Voyage in the Dark, which directly references Zola’s Nana, should be viewed in the context of the many other literary treatments of prostitution Rhys read, including Francis Carco’s 1925 novel Perversity, which she translated from French, though her translation appeared under Ford Madox Ford’s name.

Indeed, even Rhys’s decision to mine her own life for material should perhaps be contextualised within the fashion for autofiction in modernist culture, ranging from Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin to André Breton’s Nadja, which Rhys admired. No one would consider the father of Surrealism an artless writer, and neither was Rhys. Her life was painful and lived at the extremes, but its true leitmotif was her perfectionism, which produced prose of luminous purity where each word – and the ‘space’ around it, as she put it – was weighed with a poet’s care. In terms of sheer technique, she was a virtuoso.

Comments