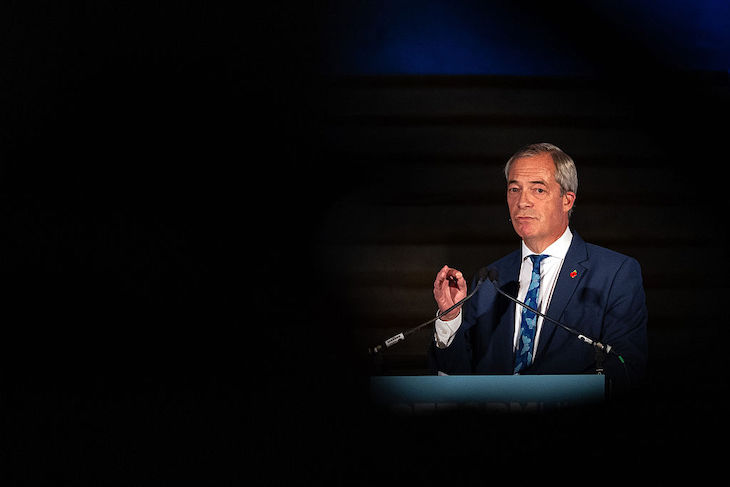

Gathered beneath the marble columns of the old Banking Hall in the City of London, Nigel Farage did what he does best. He assembled journalists, lobbyists, wonks and a few business representatives for another hour of gesticulations and clarifications. But this time was slightly different; here, there was talk of sensible reform alongside the usual messaging. Talk of ‘common-sense economics’, nods to tax, promises to put ‘Britain first’. Plenty of sound rhetoric, yes. But precious little sound policy.

Reform shouldn’t be a party of loud statements, here-today-gone-tomorrow policies and U-turns

We left with a similar sense of deja vu: bold themes, grim but correct forecasts about Britain’s economic decay and little detail. One idea, though, hardly fleshed out but familiar. Reform UK has long hinted that it would scrap the two-child benefit cap. This week, Farage clarified his position: abolishing the two child benefit cap for only working British couples, or a new tax credit for them.

A good idea? Perhaps. But the problem is in the detail. Or, more accurately, the lack of it.

Readers will be familiar with Britain’s demographic dilemma. Fertility has slumped to record lows: 1.41 children per woman. On average, couples are only having a child or two at maximum. The population is ageing and our dependency ratio is heading in the wrong direction. So politicians reach for incentives, tax breaks, childcare subsidies or, in this case, selective welfare reforms to gently nudge couples towards parenthood.

Scrapping the cap altogether would cost roughly £3.5 billion. History gives reason for caution. When the two child benefit cap was introduced in 2017 it was to curb welfare abuse. Nigel Farage said himself in 2014: ‘child benefit [should] be limited to the first two children only’. The idea caught on and George Osborne enacted it in 2015.

That was the political mood back then. Voters were weary of tabloid tales about families living on generous benefits with three or more children, subsidised by working people. It was a politically shrewd call for fairness. Now, more than a decade later, a new spin is given. The old policy is ‘cruel and anti-family’. It’s quite the U-turn, though perhaps not a surprising one for a man who reads political sentiment like weather patterns.

Restricting the abolition to low-income British working couples would be much cheaper than scrapping the cap entirely. As low as a few hundred millions of pounds – a small number next to full abolition. But this is just one idea from Reform.

Farage is thinking about a tax credit for British working couples. It sounds good. It is pro-family, pro-British, pro-Britain. In practice it raises the same questions that have dogged family policy for decades. But there are various questions one could raise.

Would a few hundred pounds a year really persuade couples to have more children? How much would it cost? Would it be universal or means-tested? And who exactly counts as a ‘working couple’? How would it differ from the old model?

Without those answers, the plan risks becoming yet another spending commitment, an expensive welfare gimmick. Easily abused, politically convenient, and fiscally loose. The bigger issue is fairness. The cap was introduced after the financial crisis, when austerity made working couples tighten their belts. The question on everyone’s minds at the time was, why should those on benefits have larger families subsided by those who could barely afford two children of their own?

Reversing that logic now, without addressing the real barriers to family life like high childcare costs, stagnant wages and unaffordable housing is to miss the point. Britain has a benefits problem and a cost-of-living problem.

What Reform is offering now is a fiscal soup of compassion, a hint of economic nationalism, and a sprig of fiscal populism. The next election is still four years away. This is time enough to turn slogans into spreadsheets. But if Reform wants to be taken seriously as a party with serious policies, they need to do more than gesture at problems.

Scrapping the cap or introducing a the credit may sound bold, but unless Reform can explain how much it would cost, how they would prevent fraud and actually lift birth rates, it risks looking like another spending policy rather than a genuine reform.

Reform should realise it has many years until the next general election. This isn’t a party founded on ideology. If Farage wants to lead a party that listens to voters and delivers what they want, then he can’t lock himselfinto policies based on what people say they want today. The world, economy and opinions are changing rapidly.

The economy will change, the numbers will shift, and the moment will pass. Reform shouldn’t be a party of loud statements, here-today-gone-tomorrow policies and U-turns. If you want to get people talking, don’t let the talk be about how little you actually know. Farage doesn’t need a policy for every topic, but he does need to show he understands the difference between populism and a plan.

Comments