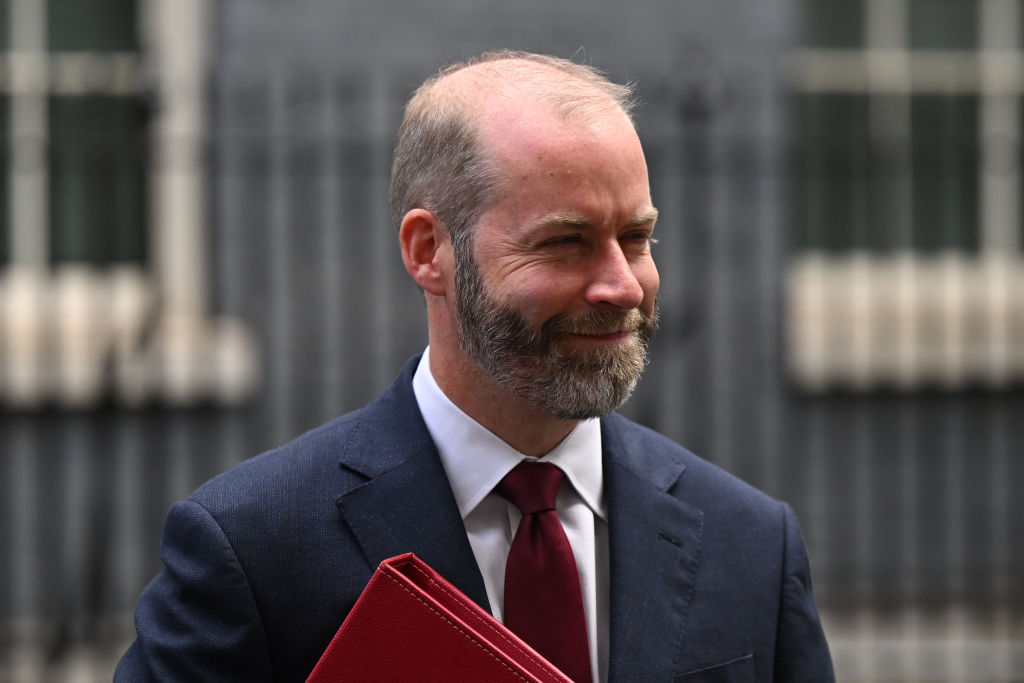

I am sure that the business secretary Jonathan Reynolds picked up many useful skills in his previous job in local government, but does he really know more about how to run a business than the people who run one of the world’s most successful companies?

Apparently, yes. Asked on LBC where his comments about encouraging remote working fitted in with Amazon’s decision to order its staff back to work five days a week in the office he said:

If I was talking to a business like that I would say that every piece of evidence that has ever been collated suggests that flexibility, when agreed between employer and employee, is good for productivity and is good for staff resilience. You get to retain your staff for longer, you get more out of them.

But is that what the evidence really says? As on so many issues, if you want to look for evidence on working for home (WFH) which matches your pre-conceived ideas it is generally possible to find it. Those who favour WFH like to quote a study by Nicholas Bloom of Stanford University from 2013, well before the pandemic, which looked at the example of a Chinese travel agency, Ctrip, which experimented with some of its call workers working from home – the impetus in this case being the high cost of office accommodation in Shanghai. The study claimed that staff were 13 per cent more productive when working from home. There was, however, a caveat. The study had excluded employees who had children, as well as those who had no room to work in other than their bedroom.

Another study that supporters of WFH like to quote concerned 30,000 workers in the US aged between 20 and 64 earning at least $20,000. Booth School of Business at University of Chicago, which conducted the study, reported that six in ten workers reported themselves to be more productive while working at home, with 14 percent saying they got less done. But this was purely a self-reported study. If people were enjoying working from home, you might expect them to report a rosy view of their own productivity.

There is, however, plenty of evidence on the other side of the coin, too. A study by the Becker Friedman Institute of Economics at the University of Chicago looked at 10,000 staff at an Asian IT company. When asked to work from home, their output declined slightly, but they reported an 18 per cent increase in the number of hours they were working. Productivity per hour fell by between 8 and 19 percent.

A Japanese study that looked at 1579 companies found that productivity while working from home was only 60-70 per cent of that when employees were working on business premises. Interestingly, half the companies taking part in this study were in the manufacturing sector – where by its very nature working from home is more difficult.

All but the first of these studies comes with a caveat: all were conducted during or shortly after the pandemic, when rapid changes to working practices were forced on employers. It can’t be assumed that deliberate experiments in WFH would come up with the same results.

It is clear, however, that the evidence base for productivity and WFH is a rich buffet from which anyone can take what they like. But it is patently untrue to claim, as Reynolds does, that every study has come down in favour of the claim that WFH improves productivity. I can appreciate that the Business Secretary might be annoyed by Amazon spoiling his policy announcement on WFH by announcing a contrary move on the same day. But wouldn’t it be wiser if Reynolds – and the entire government for that matter – left it to businesses to work out what working arrangements are best for them? That’s the trouble with a government with interventionist inclinations: it just can’t keep its nose out.

Comments