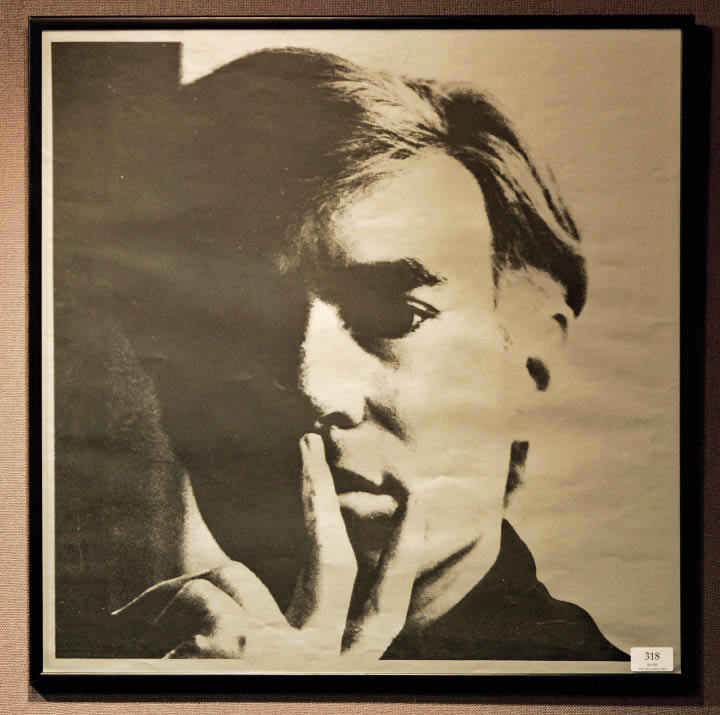

If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.

Much the same thing has been said by many artists and writers, but seldom has this proposition been so tested as it is by ‘32 Campbell’s Soup Cans’.

In the Factory, as he called his atelier, Warhol made paintings of photographs, casually silk-screened prints of blown-up acetates of blow-ups from contact sheets of original negatives, copies of copies, images of images. He inverted high and low culture. He expressed something, defined something, about our psychic relationship to the stuff that surrounds us, in the way that Freud or Proust did. He changed the way we see, and he changed art.

And despite its spectacular inscrutability, in his early and best work there is ample evidence of personality: the sweet and funny side, in the ‘Marilyns’ and ‘Elvises’, and the cool and cruel side, in ‘Electric Chair’ and ‘Burning Car’. This evidence is retrospectively amplified because — like Wilde — Warhol gave his genius to his life, and for him his art was simply another advertisement for his non-existent self. He was the product.

In Andy Warhol: His Controversial Life, Art and Colourful Times, Tony Scherman and David Dalton (both are associated with Rolling Stone, and the latter worked for Warhol) concentrate on the best years, from 1961 to 1968, but also give a full account of his early life.

He said he ‘came from nowhere’, which was true in a way, but the Warholas — he dropped the ‘a’ as early as 1948, when he was 20 — were actually Rusyns, from Miková in Slovakia, compared by the authors to Borat’s village. At the turn of the century his father, Ondrej, moved to Pittsburgh, where he worked as a labourer and coal miner and, having married a fellow Rusyn, raised three sons.

Andrew, the youngest, was highly strung and sickly, afflicted for life with ‘very prominent hemangiomas, or collections of blood vessels, chiefly on the scrotum’, which ‘looked like little collections of rubies, lots of them’, and which, with his bad complexion, potato nose and premature baldness, inhibited his romantic progress. A friend recalled that all he ever heard from Warhol on the sex front was ‘a sort of whining — “When is there some for Andy?” Along those lines. Plaintive.’ For a while in 1967 he had a quasi-boyfriend called ‘Rod La Rod’, an oaf from the Deep South, who used to chase him around, tickling and goosing him: ‘That was Andy’s idea of sex.’ (Apart from voyeurism, of course.)

After majoring in art at Carnegie Tech, where he had difficulty with perspective, he moved to Manhattan and became a successful fashion illustrator, turning out stylish drawings of handbags, gloves and shoes — as he continued to do long after he became a famous artist. He also acquired a silver wig, and launched himself on the gay scene, but with hardly more success than he enjoyed on the art scene, then dominated by the macho Sturm und Drang of Abstract Expressionism. In his own work Warhol was already appropriating advertisements and comic strips — Popeye, Dick Tracy, Superman. When he saw Roy Lichtenstein’s ‘Girl with Ball’ he was furious: ‘Ohhh! I do work just like that!’

Scherman and Dalton argue that Warhol’s background gave him an edge over his fellow Pop artists. As the poor, sick, ugly, gay, provincial son of immigrants, his worship of consumer products, especially celebrity, was more sincere than ironic, and this gave his best work a positive charge. For all its affectless camp, it is celebratory as well as satirical.

Although of an ‘unintellectual turn of mind’, by introducing the silk-screen process he reversed ‘the magical appropriation of reality by photography that had plagued painting’. And with his Brillo boxes, according to one critic, he ‘effaced those symptoms of modern art — personality and creativity — which have been sanctified to the point of blasphemy’.

His metaphysical problem was that by killing the artist he was killing himself. So in 1965 ‘Wendy Airhole’, as the Abstract Expressionists called him, announced his retirement as a painter, and turned his talent to film, with

movies in which the camera didn’t move, the actors didn’t act, the script was plotless and pointless, and the dialogue only a mad approximation of human speech.

Having made a killing with Chelsea Girls, and appropriated the Velvet Underground, he then launched himself on a booming college lecture circuit, at between $750 and $1,500 a pop. Barely capable of speech himself, he paid a friend to wear a black leather jacket and sunglasses, spray his hair silver, and fly out to Montana or Utah, where he wowed them with witty eloquence:

The press ran after me and said, ‘Mr Warhol, you’re so intelligent! Everyone’s got it all wrong, you’re really smart!’

Cool, cruel Andy tends to predominate in this portrait. Told that one of several friends and unpaid ‘superstars’ had killed himself, he said:

I wonder when Edie [poor Edie Sedgwick, his debutante alter ego] will commit suicide. I hope she lets us know, so we can film it.

By 1968 he was emptied — ‘I hate art,’ he said. A Swedish critic wrote:

He who has met Andy Warhol when he has taken off his obligatory black glasses sees a face that is as dead and devastated as a war front after the action has moved on.

The previous year the Factory had been infiltrated by Valerie Solanas, founder of the Society for Cutting Up Men. On 3 June 1968, enraged by his failure to give her money, or to return the manuscript of her play Up Your Ass, she shot and nearly killed him. ‘Do you realise,’ said Henry Geldzahler of the Met, ‘what this does to the value of the paintings? Don’t tell anyone I said that.’

Warhol survived for nearly 20 years, earning a million or two dollars a year making dead portraits of German industrialists’ wives. He began by painting celebrities to draw attention to himself, and ended a celebrity painting the rich. After the shooting he just vanishes into surface, a wax automaton, neither living nor dead, the image of an image, the copy of a copy.

Andy Warhol is superfluous, but tells us all we might want to know.

Comments