It’s not every J.D. Wetherspoon’s pub that has a preservation order slapped on it. In fact, I’m prepared to bet there’s only one: The Trafalgar in Portsmouth, Grade II-listed in 2002 for its mural by Eric Rimmington.

Rimmington was 23 in 1949 when he won the commission to decorate the clubroom of the old Trafalgar House Services Club and chose to paint a view of Portsmouth and Southsea Station with passengers coming and going on the platforms. More than 60 years on, comings and goings on station platforms haven’t lost their fascination for the artist, though for his latest London show at The Millinery Works he has plunged down the metropolitan rabbit hole to pursue his observations underground.

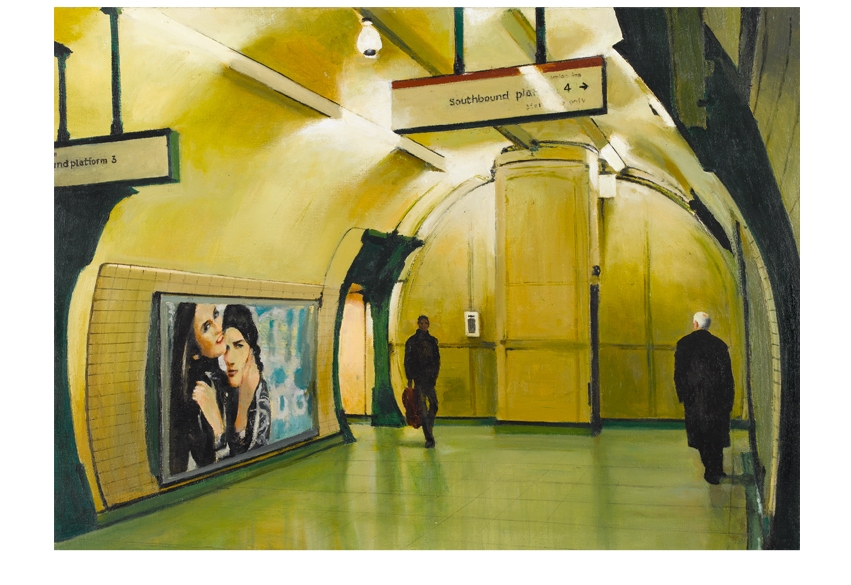

For the past six years, Rimmington has been roaming the Underground, haunting its warren of passages, stairs and tunnels, immersing himself in its subterranean atmosphere — especially its light — and indulging his visual curiosity about ‘all the impedimenta and bits and stuff’ that most Tube travellers scrupulously blank. The result is a collection of 43 paintings which, between the worn red brick of the old Circle and District Line platforms at Paddington and the armour-plated strip-lit corridors of the Jubilee Line extension, reveals a world of dizzying variety held together only by its enamel signage.

Rendered in paint, the red London Underground roundel and its little echo, the ‘No Smoking’ sign (David Hockney would have painted these out), acquire a curious charm; even the bleak black-and-white ‘STAND CLEAR — DOORS CLOSING’ warnings over the lifts — flouted by opportunists dragging wheelie cases — greet us like old friends. But Rimmington’s eye also finds oddities in the familiar. In ‘Arches’, a dark tunnel disgorging a rushing train rhymes disconcertingly with the illuminated arch of an empty stairwell; in ‘Going Down’, the skewed perspective of descending strip lights sidesteps the expected vanishing point, while the treads of the down escalator play Escher-like tricks, appearing as risers.

The people behave more predictably. We’ve all been that bumbling woman dithering in front of the Piccadilly line map in ‘Routefinder’, and we recognise the distracted, crumpled figure with the carrier bag framed in the train door, awkwardly ‘Text Checking’. Rimmington is a dedicated follower of ‘the perambulations of people walking around, across, up and down’, but he’s just as keen an observer of stillness. In ‘Sunlit’, commuters at Paddington are ranged along a platform like objects on a shelf in one of his better-known still-life paintings, awaiting the epiphany of a train. There’s always that sense of suspended animation down the Tube, of holding our breath until we get back above ground, accentuated by the accelerated activity of station foyers captured in the dramatic image ‘Running’.

This is not Rimmington’s first underground campaign; an earlier series of paintings was shown at the Mercury Gallery in 1999. Those carried a faint whiff of underworld mythology, but there are no Eurydices or Persephones here. The title ‘Angel Gates’ is as close as we get to the otherworldly, and that’s just a comment on the wing-shapes of the ticket barriers. Unlike Mark Wallinger in his airport video ‘Threshold to the Kingdom’, Rimmington doesn’t invite comparisons between public and spiritual transport. He lets us fantasise about the Hopperesque young woman in ‘Angel Gates’ but his real interest is in the movement of people in space, the bunching or thinning of a crowd approaching around a wide tiled bend or disappearing down a tight metal throat. The space is an equal partner in his drama and sometimes commands the stage on its own. In the noirish image ‘Whale’, a backbone of strip lights casts rib-like shadows on the curved walls of an empty Arsenal corridor as it waits to swallow the next shoal of Jonahs.

Rimmington is captivated by the idea that the glistening tracks and passenger streams of the Tube network have replaced London’s underground rivers. Watery allusions surface in ‘Shell’, a conch-like section of a Jubilee line passage, and in the greenish aquarium light of ‘Interchange’. There are art-historical allusions too, for them as want them: glimpses of Poussin in a classical architrave, of Piranesi in a prison-like stairwell, of Malevich and Vasarely in patterns made by floor tiles, of Mondrian and Nicholson in the framing of squares and the squaring of circles. It’s too easy to be deceived by their painterly perfection into taking Rimmington’s images at face value, when there’s nothing simple about them but their subjects.

I was amused to see, in a painting of Edgware Road Station, a poster with the slogan ‘LIFE IS A LAUGH’. Rimmington didn’t remember this — who would? — but the poster advertised a sculpture installation by Brian Griffiths commissioned in 2007 by Art on the Underground for the disused platform at Gloucester Road. Assembled from a giant panda head, a motorway lamppost, a caravan and a heap of sand, Griffiths’s installation was intended, so the publicity said, to highlight the transitional nature of the site. Funny to think that a memory of this piece of artistic ephemera will be preserved for posterity in one of Rimmington’s Underground paintings long after Art on the Underground has gone down the tubes.

Comments