The Prisoner of Second Avenue

Vaudeville, until 25 September

Lingua Franca

Finborough, until 7 August

Neil Simon has received more nominations from Oscar and Tony than any other dramatist in history, so his comedies ought to be playing constantly in London. But revivals of his plays are rarities. Something of the Simonian essence seems to fall off the plane mid-Atlantic. Perhaps it’s the awareness that we’ve seen his favourite terrain, bourgeois anguish, charted more vividly and tellingly by homegrown talents. Simon’s conception of human character is fundamentally soppy. More trickster than magician, he builds his drama by postulating secure, loving relationships and smothering them in frothy layers of petty bickering.

This succeeds in maintaining our interest because the characters’ cordiality never alienates us, but it never challenges us, either. He’s not a searcher but a comforter. He hasn’t the caustic graces of Mike Leigh nor the heaven-sent scattiness of Alan Bennett nor Tom Stoppard’s super-intelligent curiosity. His dialogue reaches constantly for one effect, quickfire self-lacerating petulance, which is fine as far as it goes. It just doesn’t go very far.

The Prisoner of Second Avenue is set in New York during the 1971 recession. There’s no plot. Mel loses his job at an ad agency and with the help of his adoring wife Edna he muddles through somehow. That’s it. Mel may be a lousy adman but he’s a champion whiner. After ten years of analysis his therapist has died and he’s disinclined to find a replacement. ‘I’d have to spend $23,000 filling in the new one on all the things I spent $23,000 telling the old one.’ Many of Simon’s jokes originate in arithmetic. The couple’s flat is burgled and Mel refuses to make a claim because his insurance premiums will rise. ‘You pay twice as much to insure half as much stuff.’ Perhaps this explains Simon’s popularity on Broadway. The gags are tailor-made for the bankers and brokers who can afford a night out in New York.

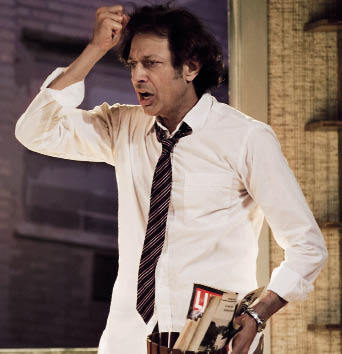

Jeff Goldblum, always a splendid sight on stage, is cast against type as a middle-aged loser. To play Zeus, all Goldblum would have to do is run a comb through his hair, so it’s a perverse pleasure to see him souring his breezy charm and transforming his pole-vaulter’s rangy gait into the stoop and shuffle of the disintegrating Mel. Opposite him Mercedes Ruehl has little trouble impersonating Edna, the doting doormat.

Terry Johnson’s production brings out the play’s easy-listening textures with admirable skill, and, though I didn’t laugh at many of the jokes, I think I understood a fair portion of them. But then I’m not the target audience. A vintage play by a cherished New York writer, starring two Americans who have had, shall we say, an amplitude of years to build up a loyal following, is clearly aimed at homesick tourists enjoying the new muscularity of the dollar. It’s a two-hour Happy Meal. And though it may not be London’s most penetrating work of art, as a piece of commercial calculation it’s pretty near perfect.

Another dramatist of Neil Simon’s vintage, Peter Nichols, is best known for hit plays such as Privates on Parade and A Day in the Death of Joe Egg. Having fallen out of favour since his 1970s heyday, he’s now sitting on ten or so scripts that he can’t get produced. Enough for a festival. The small but estimable Finborough Theatre has staged the world première of Lingua Franca, Nichols’s account of his spell as an English teacher in Florence in the 1950s. The script is an odd blend of drama and monologue. The classroom experience is represented by teachers giving lessons to unseen students whose reponses are heard on tape. Recorded lines are always tricky on stage. Making the show straddle two time scales, then and now, seems to harm the contract between player and audience in some unfathomable way.

The plot traces the romantic entanglements of Steven, an English graduate who wants to become a writer. At first he inclines towards Peggy, a hearty English gal, but is later drawn to Heidi, a buxom Bavarian blonde who dresses in blood-red skirts and praises Hitler’s ‘idealism’. ‘He wanted a homeland for the Jews in Madagascar.’ Torn between safe English femininity and intoxicating Nazi sex appeal, Steven attempts to get the best of both worlds. He tries the jackboot for size, but not before planting a few seeds on home turf as well.

Nichols hasn’t made a huge effort to endear us to this self-serving love-cheat. Steven comes across as a callow and untested idealist, like Jimmy Porter without the acid-soaked rhetoric. Elsewhere, the staff-room is scattered with exiles and misfits from Russia, Australia and beyond, and, while each character is absorbingly portrayed, the play as a whole never compels our complete attention. One would stroll to see it, one wouldn’t sprint. But ten more plays await. Let the festival continue.

Comments