Last autumn, anyone who a) has an interest in pop music, and b) reads the weightier end of the press, would have come to the conclusion that the world was shortly to enter some kind of musical singularity, in which all of civilisation would be transformed by the 39-year-old Swedish pop singer Robyn. ‘After more than a half-decade of psycho-analysis, a relationship meltdown, the death of one of her closest collaborators and four years spent working on her masterpiece… a new Robyn is ready to return,’ a profile in the New York Times solemnly pronounced, ahead of Honey, her first album for eight years. The Guardian devoted 6,000 words — 6,000! — to her ‘seismic cultural impact’. The New Yorker rolled out its editor, no less, to speak to her for its podcast, and its reviewer said of the album: ‘Honey is loose and free and physical. It captures and concretises the wordless, ephemeral moments of bliss and sorrow that come when you’re in a crush of strangers, unsure of the future.’

And then Honey was released. It spent one week in the US album charts, at No. 40. In Britain, it soared to a mighty No. 21, and spent a whole fortnight on the chart. Which didn’t seem to be indicative of a singer who had transformed the world in her image. To be fair, one might have seen that coming, given that she had said of Honey to the Guardian: ‘I was interested in songs that didn’t have a beginning and an end… I wasn’t interested in melody at all.’ And not being interested in melody is rarely suggestive of an album for the ages.

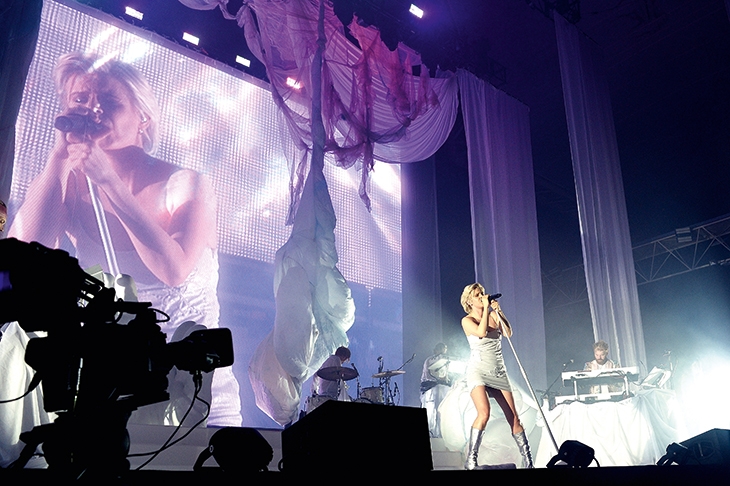

That this was a show that aspired to something profound was signified by the stage set — all billowing white sheets, like a sixth-form theatrical recreation of Scott of the Antarctic — and the fact that Robyn had a dancer. Not a troupe of oiled dancers pumping their hips, but a single, lithe chap, who got a bit interpretive. And who, during the interminable ‘Beach 2K20’ — one of the songs where Robyn wasn’t interested in beginnings, endings or melodies — appeared to be tasked with fiddling on his phone and taking some pictures. It must have meant something. I have no idea what.

But Robyn at her best is pretty terrific, even if this show — the same every night, around the world — felt slightly odd. Rather than building and releasing and building and releasing to an ecstatic climax, it felt like it peaked half an hour or so before the end, with ‘Dancing On My Own’, from 2010’s Body Talk, a song that sounds like 1,000 stormtroopers marching over a broken heart. That song exemplifies the ‘Robyn sound’ that has been claimed as her unique contribution to pop culture: hammering synths, a four-to-the-floor rhythm, an ecstatic melody and a lyric about being miserable (in this case, one about going to a club to torture herself by watching her ex with a new boyfriend). But great as it is, can ecstatic misery set to hammering synths really be considered all that original? Isn’t that pretty much what the Pet Shop Boys were doing 30 years ago? Come to think of it, ‘Dancing On My Own’ would have fit awfully well on Behaviour.

Still the ability to write words and melodies that sound like they come from someone who has actually been heartbroken, rather than someone who is trying to recall a breakup scene they once saw on Hollyoaks, is a gift in today’s pop world, and Robyn is in possession of it. When ‘With Every Heartbeat’ — her one bona fide UK No. 1, albeit 12 years ago — came up in the encores, everyone in the room seemed to be singing: every straight couple, every gay couple, every group of women, all possessed with the certainty that this song described some precise episode in their life. It was magical. It was, as the New Yorker would have agreed, an ephemeral moment of bliss. But when you’ve been promised so much, you want more than ephemera.

Comments