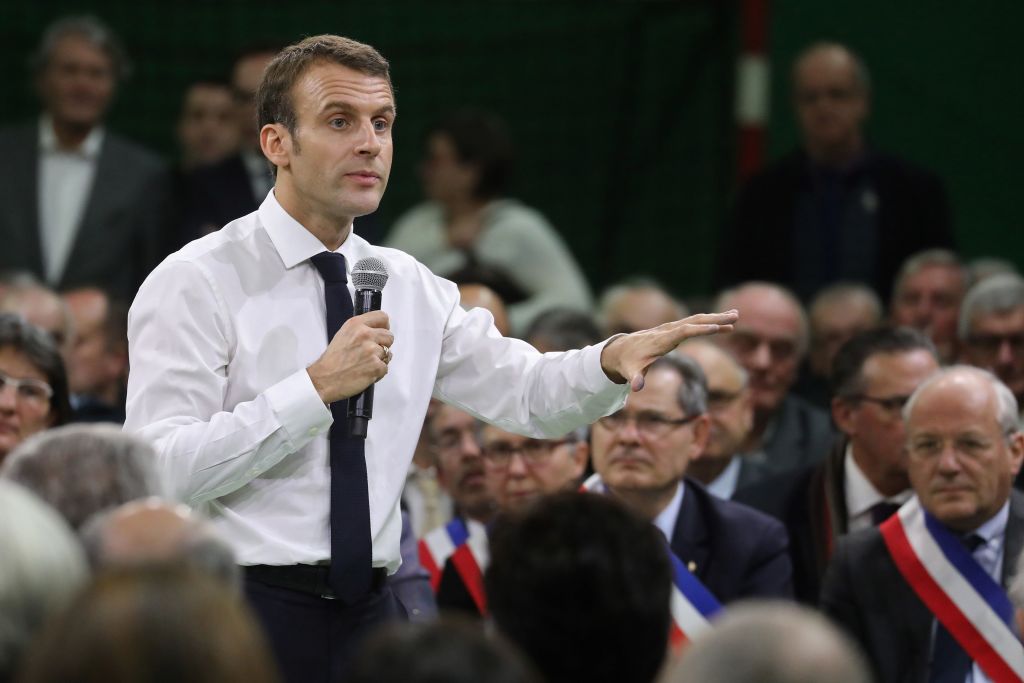

Emmanuel Macron launched his Big Debate on Tuesday and for the next two months the French people will have the chance to air their grievances in meetings and online. The consultation, in response to the Yellow Vest protest movement, has captured the media’s attention but nonetheless it was knocked off the top of the news agenda temporarily by events in Westminster.

There is an undoubtedly a touch of schadenfreude in the Élysée Palace at the Brexit farrago, a relief that another world leader is in torment.

Macron learned that parliament had rejected Theresa May’s Brexit deal on Tuesday evening, as he was nearing the end of a seven hour debate in a Normandy town hall. Describing the possibility of a no-deal as “scary”, the president added:

“The first losers in this would be the British.”

Claiming that he knew the British “a bit” (his great grandfather was a British soldier in the first world war), Macron told the audience he believes May will return to Brussels in search of a better divorce agreement. “We’ll look into it,” he said. “Maybe we’ll make improvements on one or two things, but I don’t really think so because we’ve reached the maximum of what we could do with the deal and we won’t – just to solve Britain’s domestic political issues – stop defending European interests.”

The other reason the Prime Minister can expect no favours from the French president is because he wants to make leaving as unpleasant as possible for Britain to deter his own people from getting ideas above their station. In an interview with the BBC in January last year, Macron was asked if France would vote to leave if given the chance. “Yes,” he replied. “Probably, in a similar context.”

The Gilets Jaunes’ manifesto lists a ‘Frexit’ vote as one of its demands; an escape from an EU that, as Michel Houellebecq depicts in his new novel, ‘Serotonin’, has devastated rural France.

In an interview on Radio France this week, the economist and professor Alexandre Delaigue claimed that Macron’s Big Debate will achieve little in alleviating people’s suffering because membership of the EU is not on the agenda. “In terms of public finances the principal restraint on French finances is the European restraint and all its different treaties,” explained Delaigue. “But Europe is never discussed and never even mentioned in the scope of discussions.”

Next week, Macron and Angela Merkel will hold a summit in the border town of Aachen to demonstrate their determination to, in the words of a spokesman for the French president, ‘move ahead to ensure the security and wellbeing of citizens as well as a strong, sovereign and democratic Europe.’

What that actually means is that France and Germany will continue to dictate terms to the rest of the EU. There’s never been a nation like France for playing fast and loose with the rules of the Union, ignoring with a Gallic shrug any half-hearted protestations from Brussels.

Remember in 2016 when French winemakers attacked the lorries of their Spanish counterparts in Le Boulou, tipping the contents of 90,000 bottles down the drain as police stood idly by? Spain made an official complaint to the EU about the “flagrant violation of [its] various basic principles”. But the attacks continued well into 2017, by which time Italy was also experiencing France’s inimitable approach to European solidarity. In July, Macron’s government nationalised the STX France shipyard in Saint-Nazaire to prevent an Italian firm taking majority control. Rome was outraged, issuing a statement in which they said that “nationalism and protectionism are not an acceptable basis for establishing relations between two great European countries.”

Then there is France’s policy towards the migrant crisis, which in part consists of intercepting those who cross the border and dumping them back inside Italy, a policy described by Italy’s deputy PM Matteo Salvini as an “international disgrace”.

And, of course, there’s France’s failure this year to keep within the three per cent budget deficit threshold set by the EU. The european commissioner for economic affairs is investigating the breach and will decide in May whether to sanction France for its big-spending budget. Don’t hold your breath. The commissioner is Pierre Moscovici, who is French.

The reason French presidents have always loved the EU is because it’s more or less run by them for them. But only a small tranche of French society has its snout in the EU trough, which is why Marine Le Pen believes her National Rally party will be the big winners in May’s European elections. “Those who are pro-sovereignty, those opposed to the excesses of immigration, are today choosing the nationalists amid the current division between the nationalists and the globalists,” she said last week.

Her campaign has been boosted by the defection from the centre-right Republicains of Thierry Mariani, a minister under president Nicolas Sarkozy. He made the switch after Le Pen assured him her campaign will focus on a root and branch reform of the EU rather than a Frexit. “For the first time the European election is a true issue,” Mariani said in interview last week. “Up to now the left and right, the PSE [Party of European Socialists] and the conservative PPE [European People’s Party], have shared power. This time, with Matteo Salvini and Viktor Orban, there is an alternative.”

In his first address to his new party last Sunday, Mariani took aim at Jean-Claude Juncker, describing the president of the Commission as “a notorious drunkard who incarnates perfectly the sinking ship that the EU has become”.

Macron doesn’t believe the EU is sinking. Far from it, it’s full steam ahead for the European elections with him and Merkel on the bridge. Whether they’re steering the ship in the right direction is another matter.

Comments