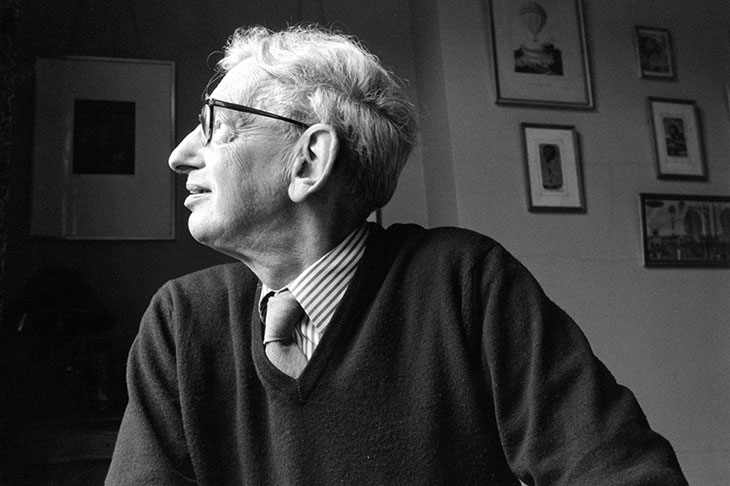

Sir Richard Evans, retired regius professor of history at Cambridge, has always been a hefty historian. The densely compacted facts in his books, the evidence of an inexorable mind incessantly at work, the knock-out blows that he has dealt to adversaries from David Irving upwards — they all characterise authoritative books by a hard-man among scholars. But in retirement, it seems, the great man is mellowing. His latest book — a biography of his friend, the historian Eric Hobsbawm — is a masterpiece of gentle empathy.

Hobsbawm was born in 1917 in Alexandria, where his father (a naturalised British citizen of Polish origins) worked for the Egyptian Post & Telegraph service. His mother’s family were jewellers in Vienna. The family left Alexandria for the Austrian capital soon after the end of the first world war. Hobsbawm began intensive reading at the age of ten and never stopped. He was already prodigiously literate when he was orphaned at 14. The storytellers and stylists of several European languages set him standards of captivating prose writing which even Marxist doctrine could not deaden. The great success of his mass-market books, which began in the 1960s, is easily explicable: he approached history while steeped in literature.

The newly orphaned Hobsbawm lived for two years with an uncle in Berlin. He declared himself a communist after reading the poems of Bertolt Brecht, and made an intensive reading of Marx. His embarrassment at his threadbare clothes and rickety bicycle made him ripe for conversion. As a communist, he could embrace poverty as a virtue, and therefore feel pride in deprivation rather than shame. Emotionally adrift, he found a version of family stability in party life and a sure sense of belonging.

In 1933, for reasons unrelated to the Nazi threat to Jewry, Hobsbawm went to live with another uncle in London’s Maida Vale. As he was already a British citizen, he could not be classed as a refugee. He spent most of his spare time studying by himself in Marylebone public library. ‘Britain was a terrible let-down,’ he recalled:

Imagine yourself as a newspaper correspondent based in Manhattan, and transferred by your editor to Omaha, Nebraska. That is how I felt when I came to England, after two years in the unbelievably exciting, sophisticated, intellectually and politically explosive Berlin of the dying Weimar Republic.

Finding London life to be ‘provincial’ and ‘predictable’, he sought his excitement (odd as it sounds) in dialectical materialism. Lenin’s theoretical works made him euphoric. He felt himself, as a young communist, part of ‘the greatest movement in the world’s history, the men who have found what Archimedes was looking for, the men who will bend the earth as though it was made of tin-plate’.

Hobsbawm was already a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) when he won a scholarship to King’s College, Cambridge in 1936. His chief mentor there was, however, a vehement anti-communist — the Bessarabia-born economic historian Maurice Postan. Postan’s lectures were ‘reminiscent of a Seventh Day Adventist in full spate at Hyde Park Corner’, Hobsbawm recalled:

Every one of them an intellectual-rhetorical drama in which a historical thesis was first expounded, then utterly dismantled and replaced by the Postan version, which was a holiday from British insularity.

Academically, Hobsbawm was a triumph: he achieved a double starred first and was awarded a research studentship in 1939. He was also elected to the Cambridge Conversazione Society, better known as the Apostles. He enjoyed its meetings because he liked arguing and hearing arguments, and he cherished their Edwardian ambiance. From his Apostolic ‘brethren’ he learnt, he wrote, ‘a deliberate lightness of touch, a slight tongue-in-cheek quality, a taste for wit, deadpan jokes, a flight from tierischer Ernst [deadly seriousness]’.

Hobsbawm was always an anomalous party member. ‘I hate uncertainty and welcome the fait accompli,’ he wrote in 1943: it might be the credo of anyone who joins a rigidly doctrinaire religious or political body. But he was also an inveterate questioner and an instinctive revisionist. As he said: ‘To doubt the theories of one’s predecessors is as natural for historians as to develop a rolling gait for seamen, and as useful.’ He regarded industrialisation as ‘almost certainly the most catastrophic historical change which has overwhelmed the common people of the world’. In an interview with Michael Ignatieff, he indicated that the deaths of 15 or 20 million people under Lenin and Stalin might have been justified if the Soviet Union had worked as a socialist model and created a radiant future for the world. But then, as he admitted in old age, he had developed as an adolescent orphan some personal equivalent of a laptop’s ‘“trash” facility for deleting unpleasant or unacceptable data’.

Hobsbawm remained a party member until the party itself collapsed in 1991. For some conservatives and liberals, the fanaticism of his socialism, his support of brutal and ruthless egalitarianism, his discounting of individual liberty and his indifference to mass killings by communist states made him detestable. He became indeed the very model of an inhumane doctrinaire intellectual. His nomination as a Companion of Honour in New Labour’s first New Year’s Honours List of 1997 accordingly aroused contempt. Hobsbawm’s persistence in his ethical aberrations was a form of self-blinding. In his youth he so fixed himself in his identity as a communist that even in maturity he could not imagine himself outside the party. His living self of 1991 was still held fast by the loyalties of his dead self in the 1930s.

When Hobsbawm’s first wife took a lover, he was enough of a Marxist sectarian to object less to her adultery than to the fact that her man was not a party member. He argued, particularly in his role as chairman of the intellectually influential Communist Party Historians’ Group, that socialism could best be achieved by the CPGB seeking affiliation with Labour and backing left-wing Labour MPs. For him the Soviet model of socialism was not the only one. The authoritarian CPGB leadership regarded the Communist Party Historians’ Group as ‘a clueless bunch of scruffs’.

By 1953 the view of Hobsbawm in Cambridge, as a security service officer reported, was that he was ‘thoroughly out of date with his communism and was still in the Popular Front era; that he would probably not survive if the Russians came’. Then in November 1956 came the Soviet military invasion of Hungary. At the time, Hobsbawm publicly defended Soviet intervention as ‘a tragic necessity’ to prevent the ‘grave and acute danger’ of a counter-revolutionary regime in Hungary. But he also signed a letter in the New Statesman referring to Stalin’s ‘grave crimes’, and to ‘the pseudo-communist bureaucracies and police systems of Poland and Hungary’.The Communist Historians’ Group broke up under the strain. To the CPGB leaders, Hobsbawm was ‘a swine’, talking ‘a lot of arrogant drivel’. Those associated with him were ‘spineless intellectuals who have turned in upon their own emotions and frustrations’.

Hobsbawm gained a global reputation after his first bestseller, The Age of Revolution, was published by George Weidenfeld in 1962. In it he jettisoned the customary political narrative. Instead he provided a thematic, analytical account of the politics, economy, society, culture, the arts and sciences of Europe. In truth, the book’s perspective was mostly Franco-British, for its two ruling themes were the global impact of the French political revolution of 1789 and of Britain’s contemporaneous industrial revolution. But Hobsbawm projected European ideas into global history with a brio that seemed new and bracing. The book has never gone out of print and has been translated into 18 languages, including Arabic, Farsi, Hebrew and Japanese.

Other bestsellers followed. In them Hobsbawm wrote with passionate conviction, with the playful grace of an Apostle and with a pithy wit that summarised his ideas and was eminently quotable. He showed scant sympathy for aristocrats (however urbane) or capitalists (however progressive), but a deep regard for exploited peasants, the oppressed proletariat and for bandits, whom he romanticised as Robin Hoods. He was a synthesiser, not a delver in archives, with astounding storage capacity in his head for vast amounts of information which he could retrieve at need. His later publisher Stuart Proffitt called him a one-man Economist Intelligence Unit.

Evans is powerfully convincing and invincibly fair in all that he writes. Hobsbawm’s two marriages, his interest in jazz and in strip clubs, and his affairs (one with a druggy Soho sex-worker) are recounted in a calm and proportionate manner without a touch of salacity. There is nothing sugary in Evans’s account of Hobsbawm’s marriage to Marlene Schwarz in 1962; but he gives a quietly beautiful picture of a strong bond between two remarkable people. It is pleasant to imagine Hobsbawm, who came to parenthood late, reading Tintin books aloud to his children and shouting Captain Haddock’s exclamation: ‘Blistering barnacles!’

I used to see Hobsbawm in his old age as a fellow member of the Athenaeum. As one might expect from someone who liked to join and belong, he was a loyal clubman. Whenever I encountered him, there was a gentle, musing smile on his face. He radiated grateful contentment. Reading Evans’s account of his domestic life, one understands why.

Comments