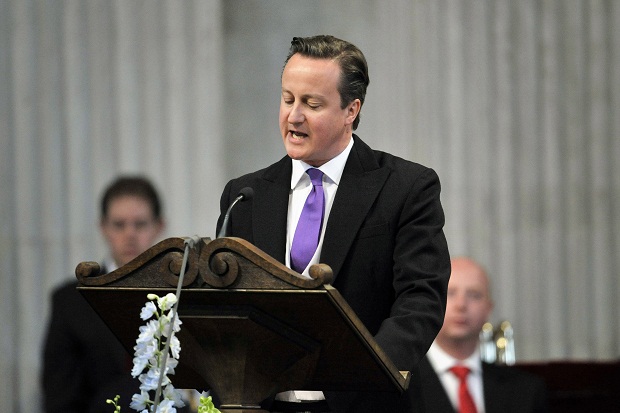

David Cameron has said Christians should be more evangelical “about a faith that compels us to get out there and make a difference to people’s lives”. In an article for The Church Times he said he wanted to infuse politics with Christian values such as responsibility, hard work, charity, compassion, humility and love.

In recent years politicians have often been shy about talking about religion, reluctant perhaps to invoke the authority of God to score a political point. William Ewart Gladstone had no such anxiety, saying in 1832: “Restrict the sphere of politics to earth, and it becomes a secondary science”. In 1880, when he was campaigning for Home Rule in Ireland, he confided to his diary that “The Almighty has employed me for His purposes in a manner larger and more special than before.” Queen Victoria thought he had a mad glint in his eye, but his zeal did mean he never stood accused of political posturing. The Spectator quoted him admiringly in 1868:

“Mr. Gladstone said one thing in his speech on Monday night which should rejoice the hearts of all his political followers, whatever their faith. “In one sense,” he said, “he was not a friend of Protestantism, for there was a great deal of it circulating in this country that he was not, and never would be, a friend of. He trusted and believed that they had a unity of belief in the blessed person of our Redeemer and of humble trust in Him; but he contended that they were bound to deal equal and absolute justice, irrespective of any question of religious persuasion; and as to his own persuasion, that of the old-established Church of England, he would at once renounce it, if its interests required him to set aside the principles of common right as between man and man.” Mr. Gladstone has sometimes been accused of being more of an ecclesiastic than a statesman,—that is, of having a faith whose roots do not strike deeper than the ecclesiastical organization to which he belongs. We hope this sentence will confute that calumny, and show him for what he is, a man with a faith in Christ that is far deeper than his faith in any of the organizations for preaching the Gospel of Christ.”

David Cameron chose his words carefully, doing his best to separate evangelism from a political crusade. It’s hard to hit the right note, as Margaret Thatcher found after quoting St Francis of Assisi (‘where there is discord, let me bring harmony’) outside Number 10. Germaine Greer was very indignant.

“If Mrs Thatcher had not simply found St Francis in her Dictionary of Quotations she would know that he was a ne-er-do-well, a lay about, a class traitor. He gave up the life of a prosperous merchant for the love of Lady Poverty. He dressed in the single garment of the peasant with no hose to his legs and begged for a living, and made of that a rule of life.

St Francis, who may be allowed to have been more intimate with God than Margaret Thatcher, certainly did not think that the free enterprise system was the best way to serve Him.”

Thatcher’s “insistence that her ideology was rooted in biblical morality goes a long way to explain the anger she aroused,” Damian Thompson noted in 1992 in an article puzzling over the religious beliefs of John Major and the other party leaders. Major’s friends and family didn’t seem to really know if he believed in God and when asked about faith on Radio 4, Major just started talking about ‘instincts and values’. Paddy Ashdown got into trouble with his Christian supporters by using New Age jargon, while Neil Kinnock spoke apologetically about his agnosticism.

“People can identify with a politician who talks regretfully about his personal failure to make a ‘leap of faith’. In any case, Kinnock is too shrewd an operator to leave it at that. His values, he says, have been strongly influenced by the passage in St Matthew’s Gospel in which Christ tells his disciples: I was hungry and you fed me, I was naked and you clothed me….‘As an article of social faith,’ concluded Kinnock, ‘as an objective for the conduct of life, I think it is very difficult to better that.’”

Kinnock managed a bit of selective Christianity rather neatly by not signing up to it in the first place. William Hague got himself into trouble by embracing it then picking and choosing his doctrines. In an article entitled ‘God, but not forgotten’, Digby Anderson took Hague to task over a lecture he delivered in 1998.

“He makes it very clear that he is in favour of Christianity, at least his curious version of it. It’s a jolly good thing. Conservatives, he explains, ‘have always drawn on Judaeo-Christian ideas’. He is most appreciative of Christians’ past work for orphans, slaves and more recently drug addicts. And he knows of fine work being done offering people ‘peace’. He is not the only one to talk of Christianity like this today. He wants the charitable works and moral tradition it is alleged to produce, but shows not the slightest interest in the thing itself, the production process and the Chief Executive whose idea it all was. Rephrase that: he wants selected bits of its moral tradition. Mr Hague gives no indication that he knows what the Church is or what Bible teaching is. Even more alarming in a professed Conservative, he seems unaware of what authority and tradition are. Clearly they take second place to what people currently believe…It seems that the heir of the Conservative tradition, he who talks so much about Burke, is into pick ‘n’ mix morality.”

This Easter, Cameron has taken the Kinnock route, admitting in his Church Times article that he’s a bit vague on the more difficult parts of faith; “Faith is neither necessary nor sufficient for morality….but faith can be a guide or a helpful prod in the right direction – and, whether inspired by faith or not, that direction or moral code matters.” Perhaps this is the magic formula: evangelism with one hand, and a-religious platitude with the other.

Comments