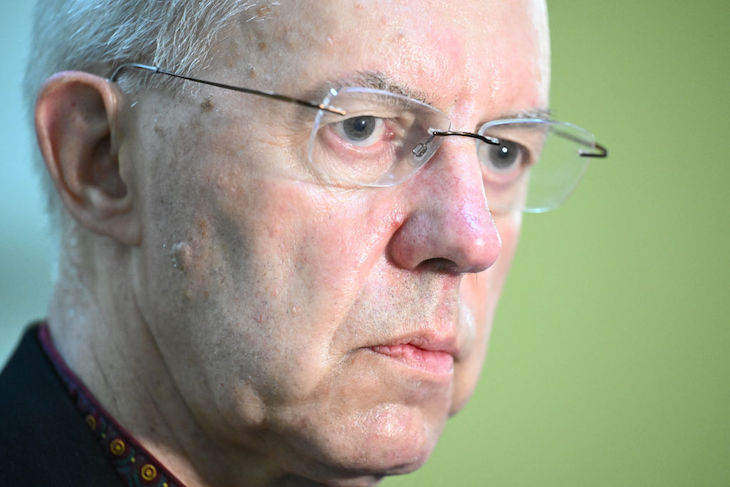

Justin Welby has said he considered resigning as Archbishop of Canterbury over the findings of the Makin Review into the serial abuser John Smyth. That report, which emerged this week, found the Church of England had, from 2013, missed opportunities to bring Smyth to justice: from that point onwards, Welby and other senior figures knew about the abuse that Smyth exacted on his victims in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

That line, ‘you will protect the work?’, is particularly telling

Smyth, a barrister and Christian leader, was accused of beating and abusing boys in the shed in his garden in Winchester. Instead of ever being brought to justice, Smyth was allowed to move to South Africa, where he ran summer camps. The authorities had not been alerted to concerns about his behaviour in the UK, and he was later charged with the manslaughter of a 16-year-old boy on a camp in Zimbabwe. Smyth died in the process of being extradited, meaning he was ‘never brought to justice for the abuse’, the review said. The review says there will have been far more victims than the figure of 30 boys and young men known to have been abused in the UK, and around 85 known to have been abused in African countries.

Smyth was active in Iwerne Camps, run by the Titus Trust, and recruited some of his victims from there. These camps were part of a conservative evangelical movement connected to the Church of England and other churches. The wider evangelical world has been going through its own reckoning in recent years, with other big names facing criminal prosecutions or resigning from their positions of influence following serious allegations. When I interviewed Welby earlier this year, I asked him about safeguarding and the camps, and whether he recognised the culture that enabled Smyth. He said:

‘Looking back with hindsight, I can just recognise it. But I was never close enough to the centre to be part of that. I was a junior dormitory officer. So, yeah, yeah. I was very shocked. I found out about it in 2013. And I was deeply shocked by that. I was sure that I mean, inevitably, in the 50s 60s, 70s, as it existed, there must have been moments where people go, ‘Well, I didn’t know of any occasion at all’. But I’d always, when I was there at the time in the 70s, and 80s, been very impressed by the, what would I say? The, well, the very ahead of its time, approach to safeguarding. So you had two or three boys in the dormitory, who you would be particularly responsible for. You would never see them upstairs. You were never to see them when they’re in a place where there weren’t lots of other people around. You were to write to them, but not more than once or twice at most a year. You were not to be in the car alone with them. Very sensible rules.’

He added: ‘I think with John Smyth he simply broke the rules. It was classic grooming. And then classic protection. This is a secret for the elite, who are properly committed to Christ. And other people were fine, but they’re not as good as this. And so you know, you are in the absolute inner inner circle where you must not tell anybody what goes on there. Because, it was so elite. Because it would damage the camp as well. I remember getting an email from a former camp leader very early on, after the information started coming out, which said: ‘You will protect the work?’ To which I wrote back and said, ‘No, I protect people’. I was very cross.’

To which I wrote back and said, ‘No, I protect people’. I was very cross.’

That line, ‘you will protect the work?’, is particularly telling, and one I recognise from my own experience on the sister camps to Iwerne in the 2000s. ‘The work’ was the matter of evangelising public school children, and everything else was a distraction that got in the way.

Iwerne had been set up for children who attended the great public boarding schools. Lymington Rushmore, the camp I attended, was for slightly less prestigious day schools, and there was a third camp called Gloddaeth which was colloquially known to cater for ‘schools in the north’. The argument was that the work would be deeper if it was confined to small groups of schools, but to most outsiders, it would have appeared deeply stratified even within the world of private schooling. I’m not entirely sure how I ended up agreeing to the invitation from a friend to attend what was sold as an outdoor activity holiday with a Christian ethos: neither of us liked sports and our families weren’t actively religious, but the camps ended up having a huge hold over my adolescence and early adulthood.

At the time, I saw them as the highlight of my year, but looking back I can now see the conditions where the authority of the big names meant they were unduly revered, and ‘the work’ that Welby was asked to protect was considered more important than other matters. Safeguarding was always, in my experience, rigorous, and the training we received was entirely standard for the time. There was a belief in taking the duty of care we had for the young people seriously. But there was also a very clear belief that ‘the work’ of the camps was the thing everyone had to protect.

In the wider evangelical world, there was a regular frustration with complaints and scrutiny into anyone who might not have been taking their responsibilities seriously: journalists who were asking questions of clergy who hadn’t been performing safeguarding roles properly were considered to have a vendetta against the important gospel work these figures were doing, rather than holding them to the standard that should be expected of them. The review points to that ‘worrying pattern of deference’, reporting one reference to maintaining Smyth’s ‘Christian usefulness and commitment’, and another letter where David Fletcher, one of the senior figures in the movement, apologised to Smyth for appearing to treat him ‘badly and unlovingly’, adding: ‘We are not, as you seem to feel, your enemies, by whom you need feel threatened, but your friends who want to support and encourage you at this time, as well as to protect the work.’ Protecting the work: the underlying principle behind the way people were prepared to keep things quiet, to circle around serious issues, and to avoid due process.

In the wider evangelical world, there was a regular frustration with complaints

There was a separate review in 2021 into the culture at the Titus Trust which ran the camps. It highlighted one area of particular interest to me and a number of contemporaries who had attended the camps but have since turned their back on them, which was the role of women. None of us contributed to that review, as it largely drew its evidence from people still connected to the camps. But we recognised what it found. The camps had a very strong doctrinal belief in ‘male headship’, which meant that women didn’t preach in meetings – not unusual within this particular strand of conservative evangelicalism – but they were also expected to wait in leaders’ meetings until a good number of men had prayed, to show their authority in those settings too. The line from Paul that wives should ‘submit to your husbands’ was a key part of their relationship teaching, one that unfortunately set a number of young women who attended the camps up for abusive marriages which they were then stigmatised for leaving. Those relationships outside the camps weren’t something the Trust was responsible for, but they showed how pervasive the ideology was: it wasn’t a case that what goes on camp stays on camp: it affected people throughout their years and lives, and was reinforced by the largely CofE churches connected through the wider evangelical network. The report then quoted one woman who said the culture created ‘a power imbalance with potentially dangerous results and engender a culture of uncritical acceptance of what ‘Bible-believing’ male leaders teach and think. This can, in turn, lead to people not seeing what is hidden in plain sight in front of them and make ‘whistle-blowing’ more difficult when needed.’ Thus, the number of people who had the power to complain and the authority to have their concerns heard was kept tight.

A culture that was in itself toxic, that also revolved around the need to ‘protect the work’: it’s not something you just see within the church but in all institutions which become rotten. Protecting reputation, diminishing the concerns and complaints of less powerful people and concentrating power in the hands of just a few at the top, who are considered so valuable that they cannot be questioned: all of these traits run through dysfunctional institutions of all kinds. The problem for the church, particularly the evangelical wing of it, is that it has long assumed itself to be better than these other institutions, a beacon on a hill shining as an example to others who could learn something. Instead, it was just as bad as those others, a truth that was masked in the quest to ‘protect the work’.

Comments